Programs offer promising potential, but confront challenges of gentrification and equitable access

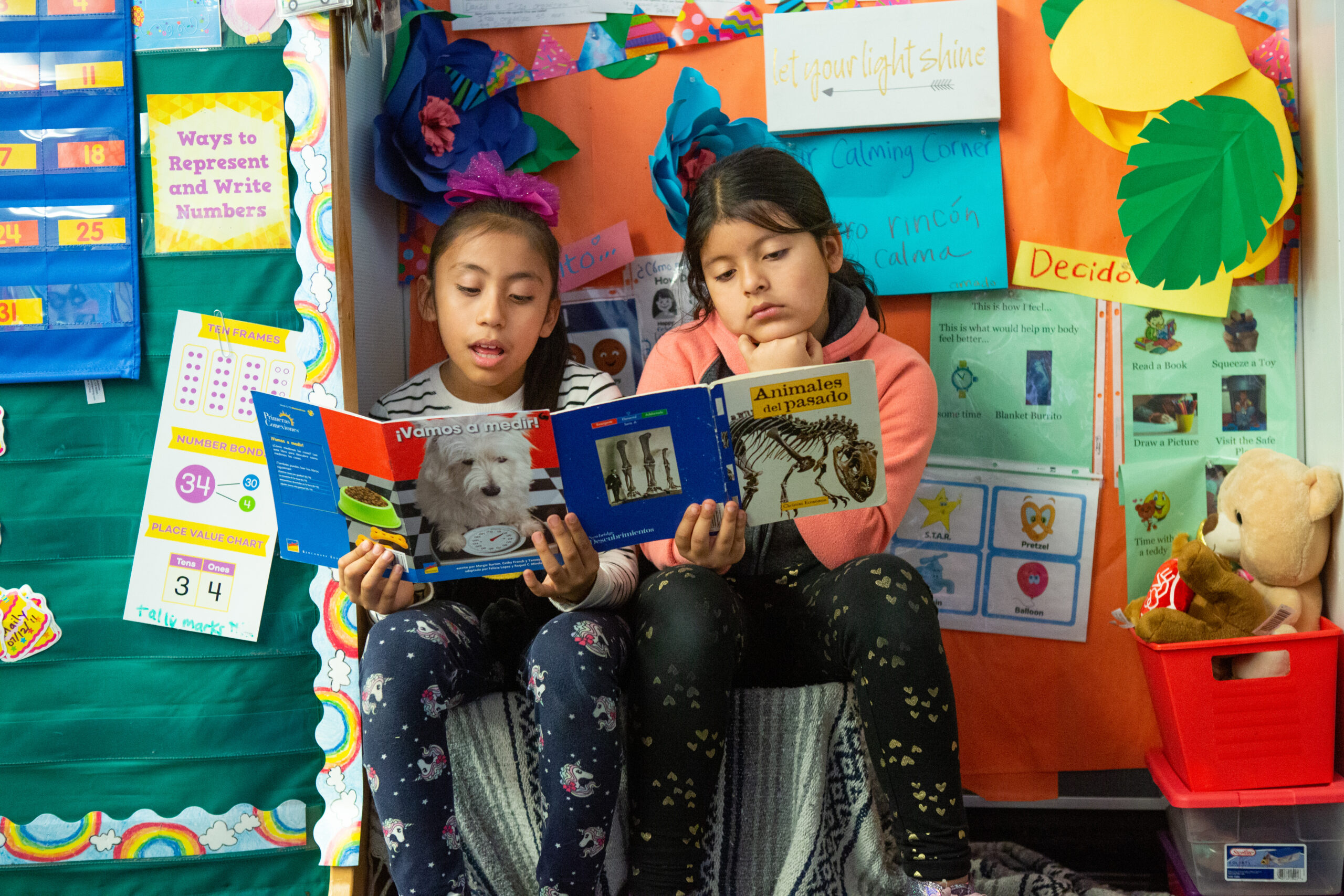

Dual Language Immersion (DLI) programs offer a powerful vision for education and the opportunity to advance equity and learning. However, as the programs grow in popularity, they also face concerns about equitable access, particularly for historically marginalized communities, according to a new research brief recently published by the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools.

The new policy brief, ”Unlocking Opportunities: How Dual Language Immersion Can Promote Equity and Integration,” examines both the promise and equity challenges of programs in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), home to the highest number of DLI programs in the nation.

“The Dual Language Immersion programs are really a bright spot for the Los Angeles Unified School District,” says UCLA education professor Lucrecia Santibañez, principal investigator for the project and co-author of the research brief.

“They see dual language immersion not only as an important instructional strategy, but as a great way to counter the loss of student enrollment and the growth in school choice programs and charter schools. There’s a lot of demand for these programs. Parents like them, communities like them. It really helps to revitalize communities and neighborhoods and schools.”

Drawing from two decades of LAUSD enrollment data, the research highlights demographic trends, community access, and how barriers, including transportation, school choice, and outreach may limit access to DLI programs for certain students.

Among the key findings:

- Prop. 58, which repealed English-only instruction, greatly expanded DLI programs in Los Angeles. English Learners make up a significant proportion of these programs.

- Expanding access to DLI programs has increased the number of students that have enrolled. However, the way some individual schools market themselves to parents may unintentionally favor English-speaking families with more resources.

- Outreach gaps and a lack of transportation disproportionately impact marginalized communities.

- Integration remains limited, especially for African American students, who remain underrepresented across DLI programs despite showing interest in enrolling in them.

The research shows that following the passage of Proposition 58 in 2016 lifting restrictions on Spanish-language instruction, LAUSD significantly expanded Spanish-language DLI programs, particularly in low-income neighborhoods, benefiting English learners and heritage speakers. In doing so, the district helped safeguard DLI programs from gentrification.

“They intentionally grew their dual language immersion programs in areas that were not necessarily gentrifying, and which have large numbers of heritage speakers such as East LA and the Valley,“ said Santibañez.

“It’s been a great way to bring people together from different socioeconomic backgrounds, different cultural heritages, [and] different languages in an intentional and authentic way that also helps attract students and families.”

The brief’s authors caution however that DLI programs, originally designed to serve language-minoritized students, are increasingly vulnerable to “gentrification.” As these programs gain traction within the school choice landscape, they may disproportionately attract more affluent, English-dominant families, shifting resources, teaching practices, and cultural priorities to reflect their needs—which could happen at the expense of the communities DLI was meant to prioritize.

While DLI programs are more widely available, they can also inadvertently benefit wealthier families with the resources to navigate complex enrollment processes, secure transportation, and access information about options, deadlines, and other procedures. In the LAUSD, for example, more advantaged families, including those from predominantly English-speaking backgrounds, are more likely to enroll in non-Spanish DLI programs, including those with Mandarin, Korean, and Japanese as partner languages. The report’s authors suggest that the LAUSD and its individual programs carefully consider how they are marketing themselves to ensure they are not unintentionally dissuading some people from enrolling. Schools should ensure that outreach and program information is accessible and culturally and linguistically responsive to African American and non-English-speaking families across the partner language spectrum.

Importantly, the policy brief also shows that African American students remain underrepresented in DLI programs, raising questions about why these programs may not be attracting African American engagement. For example, African American students may face added barriers —such as distance to programs and lack of transportation— that limit their access to DLI opportunities. Deeper inquiry into aspects of DLI design, outreach, or school climate that may be deterring interest and engagement is needed.

To help school and district leaders ensure DLI programs remain inclusive, community-rooted, and resistant to gentrification, the brief offers actionable recommendations, including:

- Increase access and transportation support

- Prioritize balancing racial and economic Integration

- Expand culturally affirming and inclusive curricula and combat deficit thinking

The policy brief, ”Unlocking Opportunities: How Dual Language Immersion Can Promote Equity and Integration,” is based on research led by Lucrecia Santibañez, of the University of California, Los Angeles and funded by the Spencer Foundation. The policy brief was published by the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools and written by Claudia G. Cervantes-Soon, Arizona State University; Lucrecia Santibañez, University of California, Los Angeles, and co-led by Erica Frankenberg, Pennsylvania State University; Francesca López, Pennsylvania State University; Sarah Asson, Education Northwest; Clémence Darriet, Harvard Center for Education Policy Research.

The full brief is available on the UCLA CTS website here.