From his retirement home in Asheville, North Carolina, Wellford (Buzz) Wilms, UCLA emeritus professor of education, watched incredulously this summer as the the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis tragically brought to light once again the national plague of racism in the name of enforcing the law.

“Like millions of others, I was horrified to see the video of him being choked to death while three others stand by watching nonchalantly,” Wilms writes in the epilogue to “Blind to Injustice: How 10 Years on the Streets with the LAPD and the People Helped Me See,” which was released in October. “I was not surprised to see protests erupt across the country as people rose up, demanding justice. After all, I lived through those violent Rodney King years, when South Los Angeles was torched and nearly burned to the ground. Now, nearly 30 years later, I look back and see that not much has improved. I can’t help but wonder: Is George Floyd’s death going to echo Rodney King’s all over again, igniting protests that ultimately die down, leaving little real progress in their wake?”

For more than ten years and in his teaching of mediation techniques to UCLA undergrads prior to his retirement, Professor Wilms looked for answers to this and other related questions. In “Blind to Injustice,” he reveals that current efforts to defund the police, restrictions on the level of force by officers in arrests, or enlisting community agencies to help prevent crime are ineffective if the white supremacy at the root of police brutality is not addressed.

“My book has taken white supremacy on – including me,” said Wilms in a phone interview. “It’s the strangest project that I have ever done, that is the closest thing to my heart that I have written, and the most difficult to publish in the environment where this is what everyone is talking about.

“Law enforcement types will read the seven or eight chapters that deal with the cops – [those who have read it] really like it,” says Wilms. “And then they get to the gangs and they say, ‘We’re not reading that about the damned gangs.’ And then the activists will read the last chapters and think, ‘Yeah, right on,’ and then they [look at the rest] and think, ‘No way do I want to read about the cops.’ And that is exactly the point of the book – that intersection between those two points of view and that’s where people need to go. Because it’s the social activists that have to come to grips with what’s happening in the neighborhoods and the relationship with the cops. And the cops need to understand better why the neighborhood people feel the way they do.”

From 2008 to 2012, Wilms rode with officers from the Los Angeles Police Department, witnessing routine patrols, vice unit operations, and crime scenes, hoping to share his experiences in a book on why the idea of community policing had not yet been successful. But in 2012, the death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin at the hands of a white neighborhood watch volunteer changed Wilms’ focus in the wake of more killings by police and anti-cop demonstrations across the nation, propelling him to extend his research.

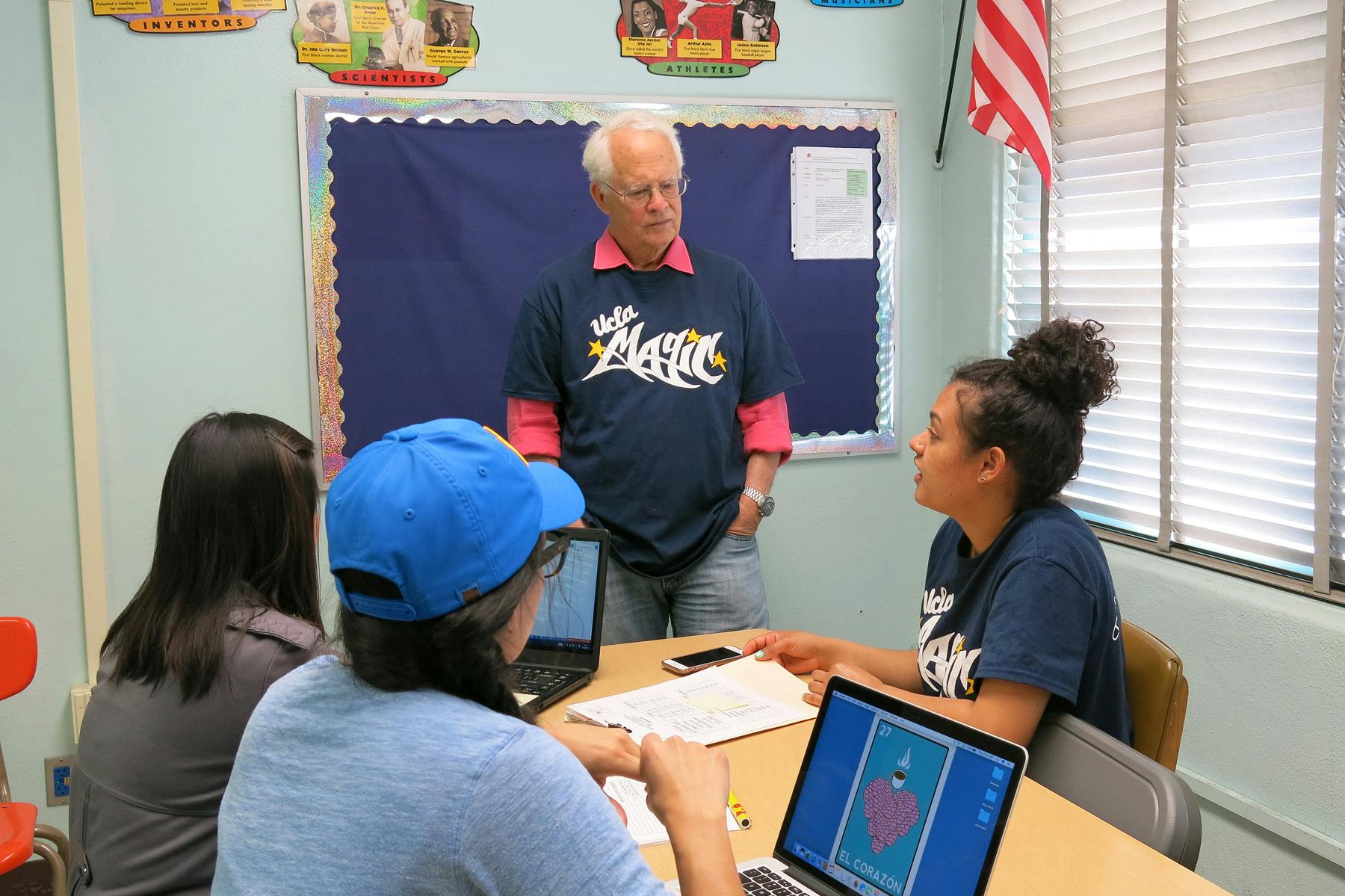

Wilms, a trained mediator, focused on South Los Angeles, and worked with the LAPD’s 77 Street division. He made connections between UCLA and Los Angeles education in the local area, including Mann UCLA Community School and Soledad Enrichment Action (SEA), where he and Avis Ridley-Thomas, his co-instructor in the University’s mediation course, founded a conflict resolution center, “staffed” by UCLA undergrads.

Wilms also took part in community organizations including Reclaiming America’s Communities through Empowerment, and OneWay, a program for young boys and men that was founded by Travon Williams, the son of Stanley “Tookie” Williams, a co-founder of the Crips.

Professor Wilms discussed with Ampersand his journey to write “Blind to Injustice,” with its many twists and turns, the friendships and trust that he was able to build along the way, and his own personal exploration of inherited racism – as the descendant of a Confederate artillery sergeant – that can potentially end through real self-examination and committed efforts toward anti-racism, not just racism denial.

Ampersand: Why do you think Americans – Black, white, and others – have until now taken in stride the scourge upon Black people by law enforcement?

Wellford Wilms: I think it depends where you’re standing. If you’re standing in a Black family, they’ve seen this before. Angie McGee, a Black officer, said to me something I will never forget. She said, “Well, you know, in the old days, we used to arrest people and put them on their knees on the curb, but you can’t do that anymore, use force like that on people.

But she said, “You know, there are a lot of people, the only thing they understand is force.” She split the hair nicely, because that’s the truth. Sometimes you’ve got to use [force], but you’ve got to be very careful how you use it so it doesn’t become the only tool that you have.

The collateral damage of slavery is exactly what we’re seeing today – that which comes from white people. The deeper I got into this, I more I realized how deeply it was in me. I worked through these deep-seated attitudes that I didn’t ask for, but they were mine. There’s no question in my mind that these attitudes have kept a handle on Black life, because that’s where the power structure is. There were inroads made by Blacks, brown [people] and Asians, but it’s still basically a white power structure. The only way it’s going to shift, I think, is it’s going to have to be generations of people who work to get rid of it in themselves first.

My family has been in this country for 400 years and some of them owned slaves. It took a lot of time for that to find its way to me. What I got out of all that was a lot of learning of what this part of life is like that I didn’t know. But it was also a descent into my own darkness, because what I could see was underneath it all, I’m absolutely convinced that white supremacy is at the root of all this.

When I was with the cops, I began to think – and it was partially true – how income is wrapped around behavior. But when I went to the other side of the street to start the mediation center, race is a real driver, and I didn’t see that. I didn’t see it in myself.

I was at a OneWay picnic, I was completely unknown. So, I’m sitting there in a lawn chair talking to Coach D, one of the three men who coach and mentor the kids, sitting across from me, and I’m telling him stories about how I’ve been with the cops, how the department has changed, going from 75 percent white to 38 percent. And he says to me dismissively, “Hey, don’t go telling me police stories, I’ve heard them all. I don’t want to hear that stuff.”

So, I went on talking to him and finally, he blew up at me. It was an impact that I will never forget because I touched something in him that allowed me to see into him, and into myself.

A month later, The New York Times ran a map of the southern United States showing lynchings in the 1920s to the 1940s, with a dot for every lynching. And it showed West Texas, north Illinois, through the East Coast and down.

Where was the biggest dot on the map? Phillips County, Arkansas, where my mother’s family lived, where I went to high school. I showed it to Coach D. I laid it out on a table and asked him, “What do you think about this?” He said, “Look, every one of those dots represents a life of one of my people. For 12 generations, we built this country. It’s still right there. It infuriates me.”

We will rationalize it and we’ll get beyond this, but … this is not the end of it until we get down into this deep white superiority. It will not change because people don’t give up power – it gets taken away from them, and I think that’s the only way it’s going to happen.

&: What do you think it’s going to take to stop police brutality and violence now and for the long haul?

Wilms: I’ve become fairly cynical – but more honest – in the last few years, seeing what I’ve seen. I really don’t think things can change until the white part of this society starts to acknowledge its own racist attitudes toward Blacks and others. Then we can have a conversation.

I think a lot of what helped me frame this book was working with people who were very different from what I was. A lot of it took the form of this mediation training that you saw with my students and former gang members, not only discovering that they wanted to help save their neighborhoods, but also their capacity for it, and the connections that can be formed. But that’s got to happen first and it’s hard to do, because it’s not something that we go out of our way to do in our lives.

The conclusion of my book, I’m urging the South L.A. neighborhoods – and this applies to everywhere in the country – to take back their neighborhoods. Stanley “Tookie” Williams – Coach Tray’s father – was recommending that. He wrote a wonderful piece in his book, “Blue Rage and Black Redemption,” about the neighborhood peace protocol. And that was his whole thing – that people have to organize themselves, block-by-block, where we have a person on every block who’s a peace keeper. And when we need to the police, we call them – but only then.

I would hope it would move in that direction, because what happens with the band of politicians in every city – from the mayor on down – is that there’s a lot of money out there, but it never gets to the OneWays. It always gets siphoned off by other interests along the way, at higher levels. I think people have to take it into their own hands politically.

One night sits in my mind. There’s a woman by the name of Paula Henderson, whose son was murdered by gang kids. She has an organization called Mothers in Charge, for mothers to get together and share their horror and their grief. She invited me to come to the church one night, down on Western and 54, a little storefront church.

I went in and they were very nice. They put me at the table with ten or 12 mothers and a couple of clergymen. I was about to ask, “Do you mind if I take notes?” and suddenly they just launched into an hour of grief about their kids. Everybody has a story. I’ve never seen so many hurt people … who were trying to deal with it. It had nothing to do with the cops anymore – it had to do with themselves processing their grief. That’s part of these communities too, that we don’t recognize. And collectively, it gets even stronger – it’s not just [one’s] own individual crying for their child.

Professor Wilms is the co-founder of the Institute for Nonviolence in Los Angeles.

All proceeds from the sale of “Blind to Injustice” go to the LAPD’s Community Safety Program and to OneWay Outreach, one of leading gang reduction programs in Los Angeles.

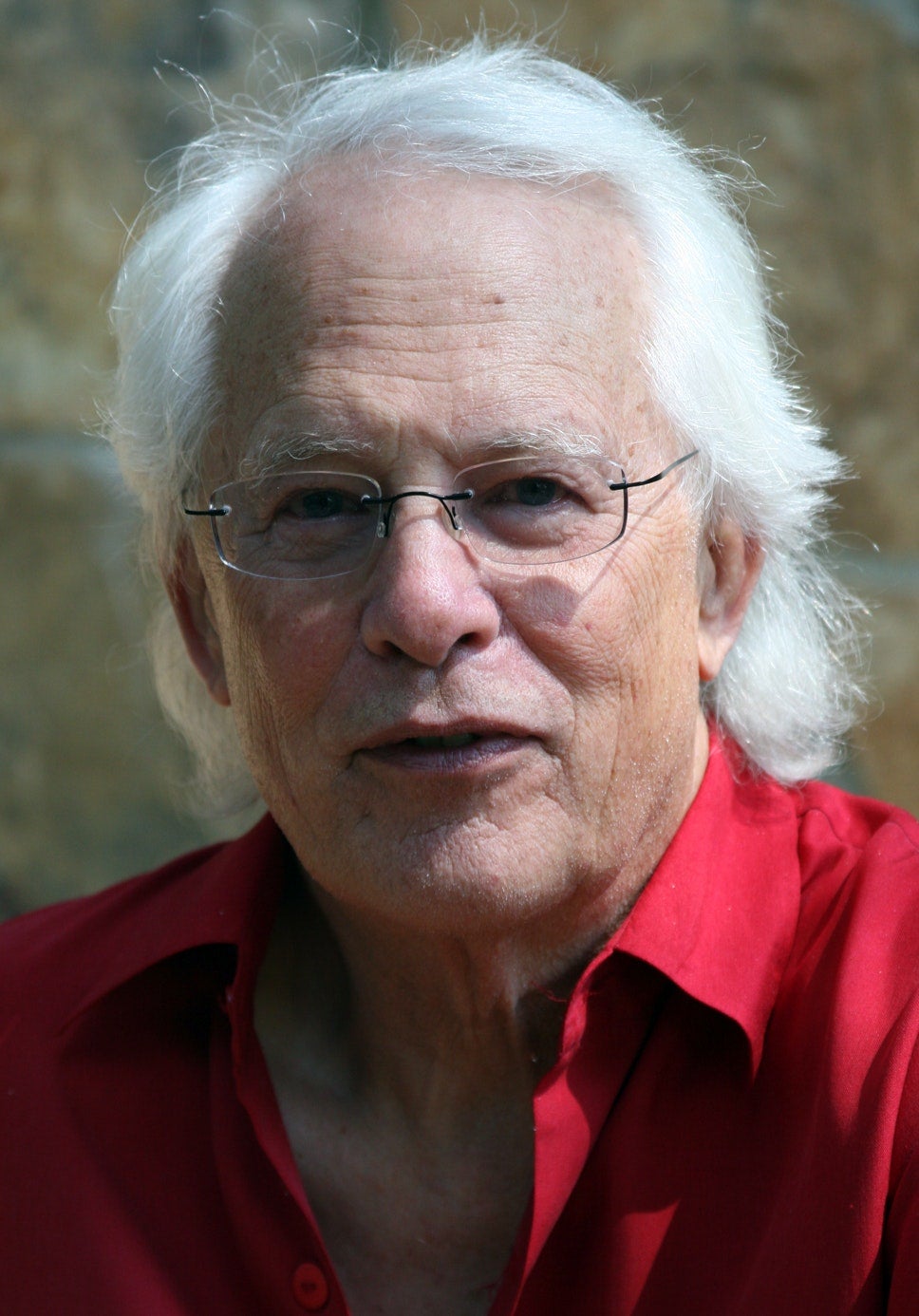

Above: Courtesy of Wellford “Buzz” Wilms