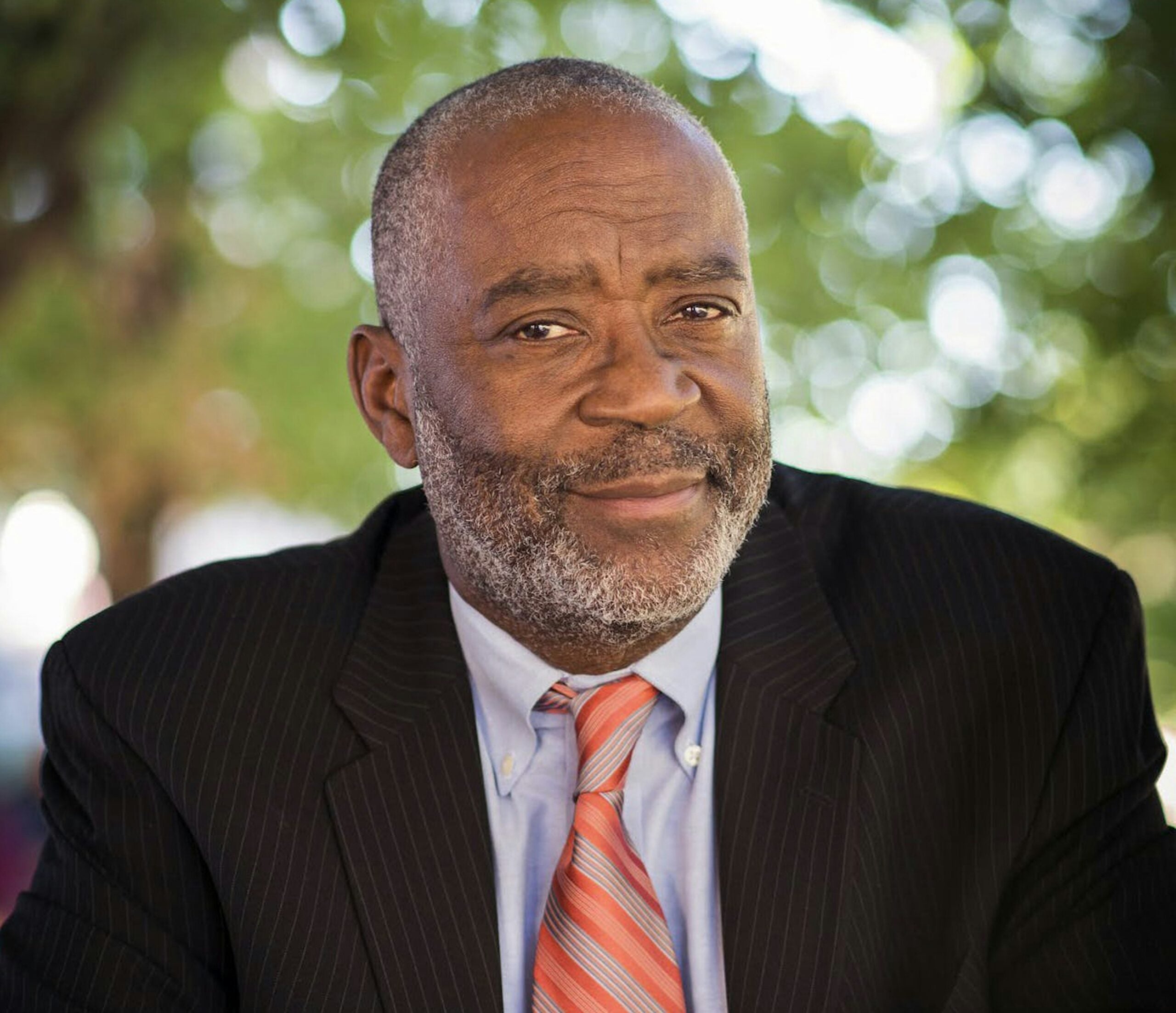

Scholar of Black and Brown trajectories in education brings expertise to African institutions and UCLA’s Bunche Fellows Program.

When Walter Allen was a high school student in Kansas City, Mo during the era of widespread racial segregation, he had teachers at Manual High and Vocational School who broadened students’ horizons and inspired them to do more.

“They were teaching these lower-income, inner city kids who had been written off by a society that didn’t expect anything of us,” said Allen in a 2016 interview. “We had classes like ‘Shoe Repair’ and ‘Environmental Sciences’ – aka ‘Janitorial Service.’ There was the notion that a good number of us would be dead or in jail or drugged out or burnt out on the street before we hit 25. And at that time also, a good number of us were being shipped off to Vietnam. You would barely graduate from high school before they shipped you off because of the draft.

“But I had these teachers who were remarkable. They would discuss ideas and ask us what we were going to do about our futures. [They] refused to accept that we weren’t capable of achieving whatever goals and dreams we set, and they refused to allow us to settle for lower standards. They took us canoeing, exposed us to theatre, and for me, planted dreams of college.”

Today, Allen, who is a UCLA Distinguished Professor of Education, Sociology and African American Studies, works to make those dreams possible for students in Africa and in South America, as director of the UCLA Capacity Building Center. Founded in 2019, the Center brings the expertise of UCLA to institutions such as the University of Ghana, Addis Ababa University, the University of Rwanda, the Association of African Universities, and the Colombia System of Higher Education, to ensure access and diversity with self-assessments of student services and technological innovation, as well as enhancing these institutions’ fundraising and development efforts.

Professor Allen came to UCLA in 1988 as a professor of sociology after serving on the faculty of the University of Michigan from 1979 to 1991. He is currently the Allan Murray Cartter Professor of Higher Education in the Higher Education and Organizational Change (HEOC) division of the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies.

The UCLA Capacity Building Center is a reboot of the UCLA Choices Project, which Professor Allen founded in 1998. His expertise includes the comparative study of race, ethnicity, and inequality; diversity in higher education; family studies; and the status of Black males in American society.

Allen is the recipient of numerous honors, including key awards from the American Educational Research Association (AERA), namely, the AERA Fellows Award (2009) and the Scholars of Color Distinguished Career Contribution Award (2016). In 2018, Professor Allen delivered the W.E.B. Du Bois Lecture at AERA’s annual meeting, highlighting the historical segregation of both faculty and students, the social and economic impact of a college degree upon Black communities, and the hopes represented by the Civil Rights Movement and Black Lives Matter. Recently, Allen received the Dr. John Hope Franklin Award from Diverse: Issues in Higher Education (2020).

Professor Allen is a member of the National Academy of Education, and earlier this year, was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. At UCLA, Allen was the 2011-12 Fellow of the Sudikoff Family Institute of Education & New Media, an initiative for the public engagement of SE&IS faculty.

Professor Allen has served as an expert witness in affirmative action and higher education desegregation cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, including Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger (for Student Intervenors); and U.S. v. Fordice (MS). He has also testified on race, education, and inequality before the United Nations in Geneva and the U. S. House of Representatives.

Allen is a sought-after commentator in international media and has been interviewed by numerous outlets including The Oprah Winfrey Show, The MacNeil-Lehrer Report, 60 Minutes, the BBC, NBC Evening News with Tom Brokaw, GLOBO- Brazilian Television Network, Jet Magazine, Le Nouvel Observateur, The Chicago Tribune, Black Enterprise, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and U.S. News and World Report. In 2017, Professor Allen served as an advisor and appeared in the documentary “Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Historically Black Colleges and Universities.”

Professor Allen’s recent publications include forewords to “Behind the Diversity Numbers: Achieving Racial Equity on Campus”; “High Achieving African American Students and the College Choice Process: Applying Critial Race Theory”; and the preface to “Measuring Race: Why Disaggregating Data Matters for Addressing Educational Inequality,” co-edited by UCLA professor of education Robert T. Teranishi, and UCLA Education alumni Bach Mai Dolly Nguyen, Cynthia M. Alcantar, and Edward R. Curammeng. In addition, Allen co-edits the Palgrave Macmillan series, “Neighborhoods, Communities, and Urban Marginality,” and has contributed to “From Ivory Towers to Ebony Towers: Transforming Humanities Curricula in South Africa, Africa, and African American Studies.”

Allen earned his Ph.D. and his M.A. in sociology at the University of Chicago, and his bachelor’s degree in sociology at Beloit College. He did his postdoctoral studies in psycho-social epidemiology while on the faculty at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

The Latest: How did you create the Center for Capacity Building?

Walter Allen: The UCLA Capacity Building Center focuses on working with universities generally, but specifically under-resourced universities. That would be Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), for example – in the United States. And then, across Colombia and South America, and the universities in Ghana that I’ve been working with… the University of Cape Coast, the University of Ghana, and a couple of smaller private institutions.

What we are doing with those institutions is, in a nutshell, helping them to work through the issues, challenges and benefits that come from a continuing focus on academic excellence, and at the same time, broadening participation [and] ensuring diversity and inclusion.

No one ever has enough money, but academia is notoriously inefficient in terms of spending the money and resources that we have. We work with them to do an assessment of their strengths and the resources that they have, make some determinations about how those resources can be deployed more effectively, consistent with the goals that the institution is setting for itself, and then at the same time, working to help them identify new funding sources.

It’s an evaluation to improve, rather than prove. The traditional evaluation either proves that you accomplished what you set out to accomplish, or you didn’t. Our evaluation approach is more along the lines of the institution sharing its goals, and us then giving them feedback to adjust course, so that they can more effectively pursue their goal, as opposed to waiting until the end of the evaluation, to tell them what they could have been doing to save money or increase participation.

In general, how accessible is higher education to most African students?

It’s not an a very different story from what you see in the U.S. and across Europe: higher education enrolls those who have privilege and who have opportunities that are not widely spread across the population. In Africa, it’s the children of parents who are college-educated, the children of the middle classes. It’s the same old story that we’ve seen, but with a twist. [African nations] are very much investing in education from K-12 to higher education, as a means to drive national development.

I was struck by the fact that there was a time that something similar operated in California, [which] also invested in K-12 to higher education as an engine that would drive the state’s economy and prosperity. Over time, the motivation to invest in the development of the population … with the expectation that you get these great returns in the future, has been waning and slipping a bit.

I’ve talked about the fact that it is not coincidental that the shift in the prioritization and the justification for investing in education writ broadly, and with higher education in particular, has coincided with the changing composition of the student population. As the system has become “browner,” there’s been less of an imperative to invest, and that ultimately cost us all.

In Africa and Colombia, they are trying to move in the direction of expanding and getting access to higher education, with an eye toward driving national development. One of their major strategies for expanding access is to make maximum use of distance education. In Colombia, with several of the universities there, it’s pretty much their definition as institutions. Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios is one of those universities where the majority of their student population accesses their courses, content, and their degrees via distance education. We’re working with them on those technologies. A key goal is sharing “lessons learned” across the global South, i.e., Colombia to Ghana.

Are those technologies readily available to the general population? Or is that another question of equity around the ability to afford devices and reliable connectivity?

The institutions are having to rethink the platforms for delivering the services, because when you start talking about the Internet, no, that is not widely available. It is tied more closely to economics. But as we were doing the assessments, we looked around and nearly everyone had a cell phone. It was hard to find spaces and folk who didn’t have cell phone access or places where the cell phone infrastructure was not good. So then, it challenged the universities, the distance education sector, to rethink how they should be delivering those services, those products.

[The internet] is extensively available in the large cities in Ghana and in Accra… obviously in large cities, Cartagena and Bogota in Colombia. When you get out into the hinterlands, you just don’t have the infrastructure for internet. As I said, people all over the country are relying on cell phones for banking, commerce, and of course, for communications. And so, what we have been encouraging, and what the institutions are starting to retool, is to deliver educational opportunities [and] courses and curricula over cell phones.

It is really an amazing and beautiful thing to see, but also a little bit disappointing. You want to push for change when people are trying to work with Excel on a small device. But the irony is that the kids … figure it out and they do it, but it’s wasteful in terms of efficiency. There has to be coordination across those different sectors that contribute to providing and delivering the educational platform. There is a very real technical aspect, as with the pedagogical and instructional standpoint, [in] making books and articles which can be quite voluminous, available over cell phones.

There are ways to do that. Possibly, they can simply streamline the statistical packages and the content, so that it is more easily handled by cell phone platforms, and there seems to be some progress in those directions. Why not downsize PowerPoint… everything that’s there, as we know, you don’t really use. Figuring out A, B, and C versions that have the minimal components, and at the same time, just shrinking their size in terms of gigabytes [to] get, if you will, a version of PowerPoint that is streamlined. It won’t have all the bells and whistles of the normal version, but it gets the job done.

Digitalization has been a real driving force in what we do, not only digitizing [content], but also equipping administrators, students, faculty, and staff that we work with to upgrade their skills, to use the digital resources to improve practice in their areas of responsibility. We’ve developed assessment tools that have been implemented and validated in Colombia at several universities. We’re implementing and further refining them in the Ghanaian context because [in] each context they share the similarities, but they have distinct, unique features. Above all else, we must always be reminded that ultimately, the best guidance comes from those people on the ground in those institutions and countries.

UCLA Distinguished Professor of Education Walter Allen (third row, at center) visits the University of Cartagena. Courtesy of Walter Allen

How did you come to study higher education in Ghana and in Columbia?

It’s been evolving over my nearly 50-year career, in terms of setting inequality and the mechanisms for addressing those inequities with the primary focus on race and ethnicity in Black students, but not solely – it’s become more of a focus on students who have the potential but who are denied access.

I’ve always studied historically Black colleges and universities, and [how] their reality is defined by limited resources, relative to or by comparison to predominantly White institutions. As I was doing the work as an expert witness in court cases with plaintiffs who were advocating for more equity and funding to historically Black colleges and universities, it became a no-brainer to try and understand how they got so much done, with so little.

If there’s a point that we all agree on – both the plaintiffs and defendants in these cases – when it comes to historically Black colleges and universities, those colleges and universities punch above their weight. They account for this incredible percentage of Blacks who have achieved professional degrees, PhDs, law degrees … and they graduate a disproportionate slice of Black students who earned college degrees. They have a fraction of the resources, and yet, they’re accounting for a quarter of Blacks who not only graduate with these degrees but go on to predominantly White institutions and excel in the professions and careers that they choose.

I began to study it in conjunction with making a simple argument to the courts that if these HBCUs can accomplish so much with so little, just imagine how their contributions can be expanded if they receive more equitable funding, and in that context also, talking about the fact that many of those schools serve non-African American populations. The medical school at Howard University [or] the law school at Florida A&M or at Southern University, have as much as 40 percent non-Black students, students from Latino and Asian American backgrounds. Increasing their capacity for non-traditional students and students – some White – who would be blocked from access otherwise, expands their opportunities and ultimately benefits the state and the society writ large.

That was one of our major compelling arguments in our University of Maryland case, which was settled in favor of plaintiffs last year to the tune of half a billion dollars of additional investment in the four historically Black colleges and universities in that in the in state. It did hinge sizably on how they served not only Black students, but a slice of Black students who don’t have privilege, who are not only first-generation college [students], as well as some White first-generation high school graduates. And, for that matter, also serving international students who come into the state, but are not able to access the predominantly White institutions; and other White, Latino, and Asian students.

How are the original aims of The Choices Project enfolded into the Center for Capacity Building?

The goal of the Choices Project was always focused on broadening access for Black and Latino students primarily, but ultimately came to focus on work for underrepresented Asian American populations. We have been doing some work on Filipinos and Southeast Asians, groups that can get lost when you don’t deal with the diversity within diverse populations.

As you come to understand what’s going on, you start seeing patterns and challenges that are cross-cutting in terms of the different groups by race and ethnicity. For example, across those groups privilege matters, in terms of whether you have access to college and the extent to which you can find yourself in a K-12 setting that enhances your educational growth, development, and opportunity. Gender is cross-cutting in terms of those disparities and inequities, and the kinds of jobs and education that one’s parents have.

I started with a narrow focus and it became broader as I started seeing all of the associated connections and pursuing those to study difference within different groups, to try and better understand how we can become more effective in this goal that UCLA has defined as inclusive excellence.

You can’t really be excellent if you’re not inclusive because you’re not dealing with the broad set of knowledge and capabilities of the population. So, that becomes a question of initial capacity building. I’ve always studied inequities. But for me, it’s also been equally – if not more – important, to say, “Okay, you’ve got these inequities, but what are the solutions?” That’s something that’s driven me over my entire career.

What are you teaching this quarter?

I am teaching a class that is a dream come true. It’s been a culmination of everything I’ve been working on my whole life, which is developing kids who are forward thinkers, who emphasize not only academic excellence, but also social commitment. That was my training at Beloit College, that interdisciplinary tradition of public service, and academic excellence in public service.

The Bunche Fellows Program is an honors program for students who have an interest in the study of African life, culture, history, and institutions. The experience that we create for them parallels what they would have if they were attending an elite private college one- of the small private, liberal arts universities or colleges, or even more so, a historically Black college or university, where the programming is student-centered. You have close relationships with the faculty, and you are stretched.

What we’ve been able to do under the auspices of the Bunche Center and with the brilliant fundraising and vision of Kelly Lytle Hernandez (UCLA professor of history and director, Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies) is find the funding to pay the kids so that they don’t have to work in the cafeteria to make ends meet. You pay them to work on a faculty research project, and they are full members of those faculty research projects in all the disciplines. Over in, say, brain and sleep research in the life sciences, policy, law, sociology, education, and of course, the cultural areas, history and English, you focus on the study of Blacklife, both nationally and globally.

These kids are getting a kind of experience. I mean, they are winning awards. One of our most Bunche Fellows Program undergraduate students won an honorable mention. She’s a second-year undergraduate, made a presentation of a poster at the national Black Doctoral Network. So it is that level of academic empowerment and development that we emphasize for these students.

My intention was, towards the end of my career, to go to a place like Howard University or Spelman, and run the honors program. It’s a dream come true that I’ve been able to have it here at UCLA. And again, that’s a way of reimagining how we do our work, where the students have closer working relationships with faculty members as undergraduates, working as if they are graduate students … growing as intellectuals and as researchers, and also doing work that is oriented towards positive social change.

Visit these links for recent articles by Professor Allen:

“Integrating Educational Technology in East Africa: One Size Does Not Fit All”

Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes Journal

“Hidden in Plain Sight: Historically Black Colleges and Universities in America”

Quaderni di Sociologia: la società contemporanea / The Color Line and the History of Sociology

“College is…: Focusing on the college knowledge of gang-associated Latino boys and young men”

Urban Education

(With UCLA Professor Emerita of Education Patricia McDonough and

Adrian H. Huerta (’16, PhD, Education; ‘M.A., Higher Education)