On a bright December afternoon, a group of young visitors to UCLA glimpsed campus life by enjoying lunch in DeNeve Commons before being led on tours of the Westwood campus by UCLA students. At the end of the day, the group was treated to a exhibition game the university’s men’s basketball team against the University of San Diego, courtesy of UCLA Athletics, with legendary Bruins Marques Johnson, Bill Walton, and Jamaal Wilkes, in attendance. The day’s itinerary was like any other welcome of prospective Bruins to UCLA, with one major difference: the visitors were young men from OneWay Outreach, a nonprofit program dedicated to erasing violence in South Los Angeles through a focus on sports, education, and mentoring.

Established in 2007 by Travon Williams, OneWay Outreach serves young African American males, who range from ages six to 22. “Coach Tray” as he is known, and two colleagues, Johnny Ross (Coach Bone), and Darryl Miller, Sr. (Coach D) meet the participants of OneWay every Saturday at Algin Sutton Park. The three men serve as spiritual, disciplinarian, and father figures to the children and youth, and provide this homelike respite from the pressures of a community besieged by gang violence, drugs, and poverty, with simple but impactful activities that include eating breakfast, playing basketball, talking, and praying together.

“Restoring Civility,” a class for UCLA undergraduates with a minor in Education, is taught by Professor Wellford “Buzz” Wilms and Avis Ridley-Thomas from Chicana/Chicano Studies. During the three-quarter course, students are trained to become conflict mediators, and then are placed in schools throughout Los Angeles to provide mentorship for at-risk students. Several of the students volunteered to guide OneWay through their campus tours in December.

Professor Wilms, organized the OneWay tour of UCLA, and welcomed the guests to DeNeve Commons by underscoring the mutual educational experience that OneWay and his students were about to begin.

“This is a two-way street: we teach and learn from each other,” said Professor Wilms of the UCLA efforts to connect with OneWay. “Today, the young men from OneWay will gain an insight to a big university where they may go after high school and will develop friendships with UCLA students who can mentor them.

“Our students will develop friendships with the young men from OneWay, whom they can guide through the pursuit of higher education. And then, UCLA itself will benefit by becoming more sensitive to the needs of all young people in Los Angeles, including those who may never have considered higher education for themselves seriously.”

Williams accompanied one of the smaller groups that the OneWay contingent was organized into for the tours, a group that he described as “the group that needs [guidance] the most.” Seeing the looks on the faces of OneWay participants and their interactions with college students – many of whom came from similar socioeconomic backgrounds – he observed that their day at UCLA was “a defining moment.”

“I am getting goosebumps looking at [the boys’] faces,” said Williams. “We African Americans – we bottle in our emotions. They’re laughing and bantering – this is a different joy for them to be here. You can see the child in them, whereas in [our] community, they learn to put on the tough act.”

Williams is no stranger to the tough act. His father, Stanley “Tookie” Williams, was a founding member of the Crips. After more than 30 years in prison and on Death Row, was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize five times for his writings against gang violence and crime. Travon Williams seeks to honor his father through his work with One Way and by being a strong parent himself.

“My father was my father, so I never looked at him as the monster that society portrayed him as,” said Williams. “What kind of relationship can you have with someone who is incarcerated on Death Row? They constantly monitor your phone calls and everything. But we had the best relationship we could have as far as me being what they call a ‘prison baby.’ But our relationship was beautiful. It affected me in a positive way.”

Williams, who has two sons of his own – one who is attending CSU Northridge – said that leading OneWay has “helped me to appreciate them more, and learn to deal with their little mishaps because I know the [parenting] problems I’m dealing with are nothing compared to the problems in the community at large. It makes me a better parent, and a better man overall.”

Andre Hayes owns a phone store in the neighborhood, and knows many of the youth that the organization serves. He says that the nonprofit has made a huge difference in the South Los Angeles neighborhood that has been nicknamed “Death Alley” by local media,and decided to join Williams and his corps of volunteers, most of whom grew up in the community, after walking in to one of the Saturday sessions taking place in the gym at Algin Sutton.

“They were in a circle, talking to the boys, and I just sat down and listened,” Hayes recalls. “I liked how it was going, so every Saturday, I’ve come here ever since.

“OneWay shows these kids that there is something outside of this. They don’t have to do what everyone else is doing – being in a gang. They may not have been anywhere, but this gives them an opportunity to see different things.”

These different things include the UCLA tour, inter-city basketball tournaments, and an upcoming tour of the Los Angeles Port and the USS Iowa, a WWII-era battleship that is now a museum in the L.A. Harbor. Sometimes, the “different things” mean teaching the youth to take a more proactive look at their own community. Once a month, Williams, Ross, and Miller drive through the neighborhood with the boys and young men of OneWay, who distribute bag lunches, bottled water, and a little cash to homeless people whom they have seen living on the streets, beneath underpasses and in camps. Some of the youth who are feeding the homeless have themselves been homeless – or continue to be – even as they address the issues of getting through school or finding work, with guidance from One Way.

Edgar Carpinteyro, is a third-year UCLA undergraduate, with a double major in Chicana/o studies and history. He served as one of the volunteer tour guides from Professor Wilms’ class, and about a month later, spoke at one of OneWay’s regular meetings about college and the steps needed to get there.

“I have learned that often, students and parents do not have access to much information about colleges and universities because of the lack of resources,” he says. “It is important for UCLA students like us to pass this kind of knowledge to the community. OneWay is taking an extra step in helping these young high school students get into college.

“Having come from a low-income community, I feel that my struggles [are relatable] to many of these students, and by sharing some of my experiences I can hopefully make a positive impact,” Carpinteyro says. “Sometimes, students just need someone to show that they care about them.”

Pearl Aquino, a fourth-year undergraduate majoring in psychology, aspires to become an occupational therapist working with college-age youth. She says that although she did not have access to the type of hands-on mentoring for college that OneWay provides, and that it would have better prepared her for higher education.

“Kids in underserved populations are in an environment that is indeed limiting in many aspects, and fails to recognize all the possibilities that they have,” she says. “Work is what they have in mind after high school, if they even reach high school, because this is what their environment teaches them: you have to work to survive. But exposing them to a path of higher education gives them the opportunity to learn more, do more, and be more than they think they can be.”

Ebreon Farris (’11, B.A., Sociology), a site coordinator from UCLA’s Early Academic Outreach Program, was a featured speaker at one of OneWay’s regular Saturday meetings in January. He says that having had the experience participating in UCLA’s GEAR UP (Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs) and the opportunity to serve as a math tutor for students at Morningside High School and his alma mater, Inglewood High School, started him on his way to a college degree.

“Although GEAR UP was strictly there to provide academic tutoring for subjects we struggled with, they also provided an atmosphere that expanded beyond our educational scope of what we could accomplish,” says Farris of the impact that the program had on students in Inglewood Unified School District. “The program followed us through high school as well. Due to the amount of exposure and belief they instilled in us, I was under the impression that college is not only intentional, but was also embedded in our future.”

Farris spoke not only to OneWay participants, but to several students and parents among the community who were connected to Williams and other members of the nonprofit. While issues such as financial aid and GPAs were topmost in attendees’ minds, there was also great interest in the college admissions process expressed by adults – several of them parents of OneWay youth – who wished to return to college or enroll for the first time.

“Growing up, I was fortunate enough to be a part of programs that enriched my education with information of the advantages we held by being disadvantaged,” says Farris. “Many students who qualify for free or reduced lunch also qualify for fee waivers for both standardized tests as well at least 12 college application fees that could amount up $700.

“Many individuals in underserved communities are not aware of the disparities that are set against them and seldom gain information that is beneficial. It is the mission of UCLA’s EAOP to ensure that these underserved communities are provided these resources and knowledge.”

Noelberto Hernandez is a fourth-year UCLA undergraduate, with a major in sociology. He says that being in the Education Minor program gives him a more intimate view of young people’s perspectives that complements his study of sociology. He hopes that the involvement of the Education Minor students with OneWay will help the youth see college as a real option, not an impossible pipedream.

“When many of these kids refer to schools like UCLA, they use the words, ‘I wish I could go there’; ‘You have to be a genius to get in’; or ‘This is a dream school,’” says Hernandez. “They talk about it as something that seems impossible to them, but in reality, they don’t have to wish, be geniuses, or just dream. With discipline and the right path, they could all make this their reality.

“This experience with OneWay has enhanced my learning with the realization that we need to make things like [college] seem less impossible for them – something that if they work at it little by little, they can achieve it.”

The gathering of high school students that Farris recently spoke to at Algin Sutton Park represented only one-third of the boys and young men who are participants in OneWay who have specifically expressed an interest in going to college. He says the realization of African American youth aspiring to college is a critical instrument for change.

“I wish I could tell those who were not present at the meeting that the preparation and competitive spirit necessary to get into college will only begin when African American youth become aware of how high they can go in pursuing their dreams and when they make it a priority to learn, to grow, and to advocate on behalf of their own futures.

“Because my parents and older siblings were not able to attain a higher education, I felt the responsibility of providing an image of success and change for the rest of my immediate and extended family,” Farris says. “The desire for a higher education is a concept that our communities are assumed to lack. It’s up to us to shift that notion that currently surrounds our communities and schools.”

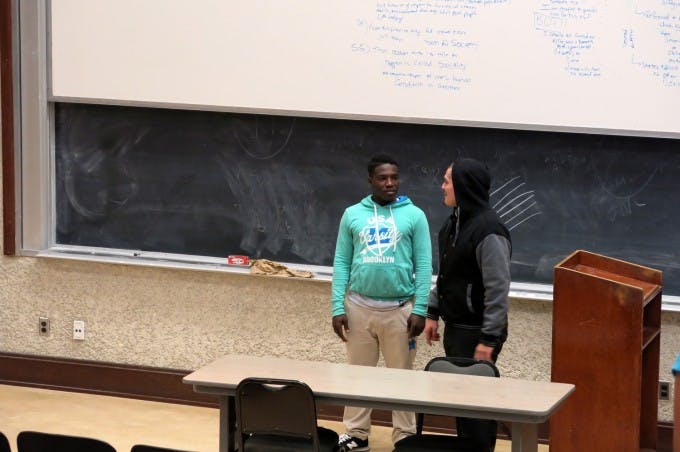

Above: Visitors from OneWay Outreach ascend Bruin Steps while touring the UCLA campus, guided by undergraduates in the Education Minor program who hope to help young African American males aspire to and achieve higher education.