UCLA Assistant Professor Anna Markowitz Makes Case for Investment in Early Childhood Educators

In 2020, the then UCLA Graduate School of Education & Information Studies made a major change, adding a new undergraduate major in Education and Social Transformation.

The purpose of the new major is not just to help students gain an understanding of the field of education, but to develop the knowledge, insight and skills needed to lead change. A big part of that is learning about social policy and the role policy can play in social transformation.

“We want to challenge our students to think big about the ways we can use education and policy to address social problems, and build a better future,” said Anna Markowitz, an assistant professor in the school and instructor in the undergraduate program.

Markowitz, a developmental psychologist whose research focuses in great part on early childhood education, teaches a class in early education policy in the undergraduate program.

Earlier this month she shared some of her research and thinking about early childhood education with students and parents attending the Bruin Family Weekend celebration.

It’s a very timely topic. Over the next weeks, the Biden administration will be working to pass the Build Back Better Act, new federal legislation setting new policies and providing funding addressing human infrastructure needs in the United States. A key element of the legislation is a groundbreaking effort to transform early care and education.

Markowitz began her lecture, “How Psychology Can Improve Policy: The Case of Early

Care and Education,” with insights and data making clear that educational equity in the United States is still a long way off.

“I would argue that in the United States one of the most pernicious problems we face is the disparity in educational outcomes, marked by indicators of race and income, indicators that represent disadvantage, marginalization, and systemic racism,” Markowitz said.

“ I really think that this gap and these differences is the core educational issue of our time. It’s not just an achievement gap, it’s an opportunity gap,” she added.

Markowitz argues that policies to improve early care and childhood education are key to addressing equity and ending that achievement gap. To erase the gap, she advocates for the development of a high-quality system of early childhood education for all children.

“We need to invest in early educators across all settings,” she says.

Markowitz’s emphasis on early childhood education draws on research showing that the gaps in achievement among children open early in life and are visible on the first day of kindergarten. While some students begin school ready to go, others have trouble working with other children, difficulty following directions, and may not recognize letters and numbers.

The brain of children develops more rapidly in the first five years of life. It is the high point for brain development, a time when basic neural circuits are formed and strengthened, creating the foundation for every other skill.

The key to learning in this period is what is called “serve and return interactions,” simple but complex interactions between a child and the surrounding environment and adults. A child “serves” something – a look, a gesture, or sound – and a caregiver responds in a way that adds to or expands the experience. For example, a baby shaking a rattle learns how to make it rattle. A young child might touch an object and a caregiver names or describes what it is. Or a child might ask a question and the caregiver gives an answer. These interactions are key to the development of memory, language, and behavior. Sensitive, responsive caregiving supports conceptual development and builds baby brains.

The question Markowitz is serving up is how can we ensure that all children, no matter who they are or where they are born or live get the experiences they need to thrive. Her response is to bring quality interactions with children to scale through early childhood education.

The challenge is that children have disparate experiences as they grow. In the United States, there is no universal system of care, instead, parents are confronted by a complex “non-system” of care. For help in caring for their children, parents turn to a series of options ranging from family and friends or a neighbor who cares for a few children, to private child care or state and federal pre-K programs. Parents often make choices about care based on what and who they know, what meets their work needs, and what they can afford.

And just as there is a range of options, there is a wide range of experiences. Those experiences are too often of low quality for most children, and particularly for those from families with low incomes challenged by costs of care and the demands of work.

“The reality is that most children are not in early childhood education settings of sufficient quality to provide a meaningful developmental boost, Markowitz said. “It’s a key driver of the gap in opportunities.”

To create a system to meet the needs of children, Markowitz suggests investing in early educators.

To underscore her point she compares K-12 educators and those working in early childhood education.

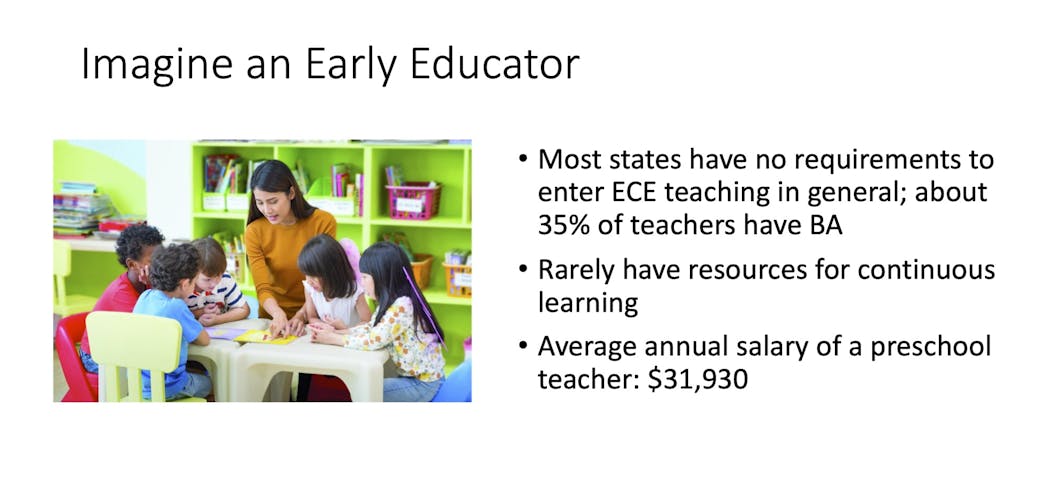

K-12 educators have significantly more education, access to training and support, and earn far more than those that work in childcare or early childhood education settings. They are more likely to grow in knowledge and skills and to stay in their careers.

Early childhood educators are also doing complex work with children at a critical time in their development, yet no state has a universal college education (BA) requirement for teachers of four-year-olds, and most states have no education requirements for child care teachers. There is little in the way of accessible funding for training and support to help these teachers get better at their jobs and strengthen their interactions with young children. And they make about half of what K-12 teachers make. The average annual salary of a preschool teacher is $31,930, childcare providers make even less.

Markowitz is part of a research-policy partnership with the Louisiana Department of Education. That research has found many pre-school teachers face real and difficult challenges that are not only stressful for them, but that have implications for children.

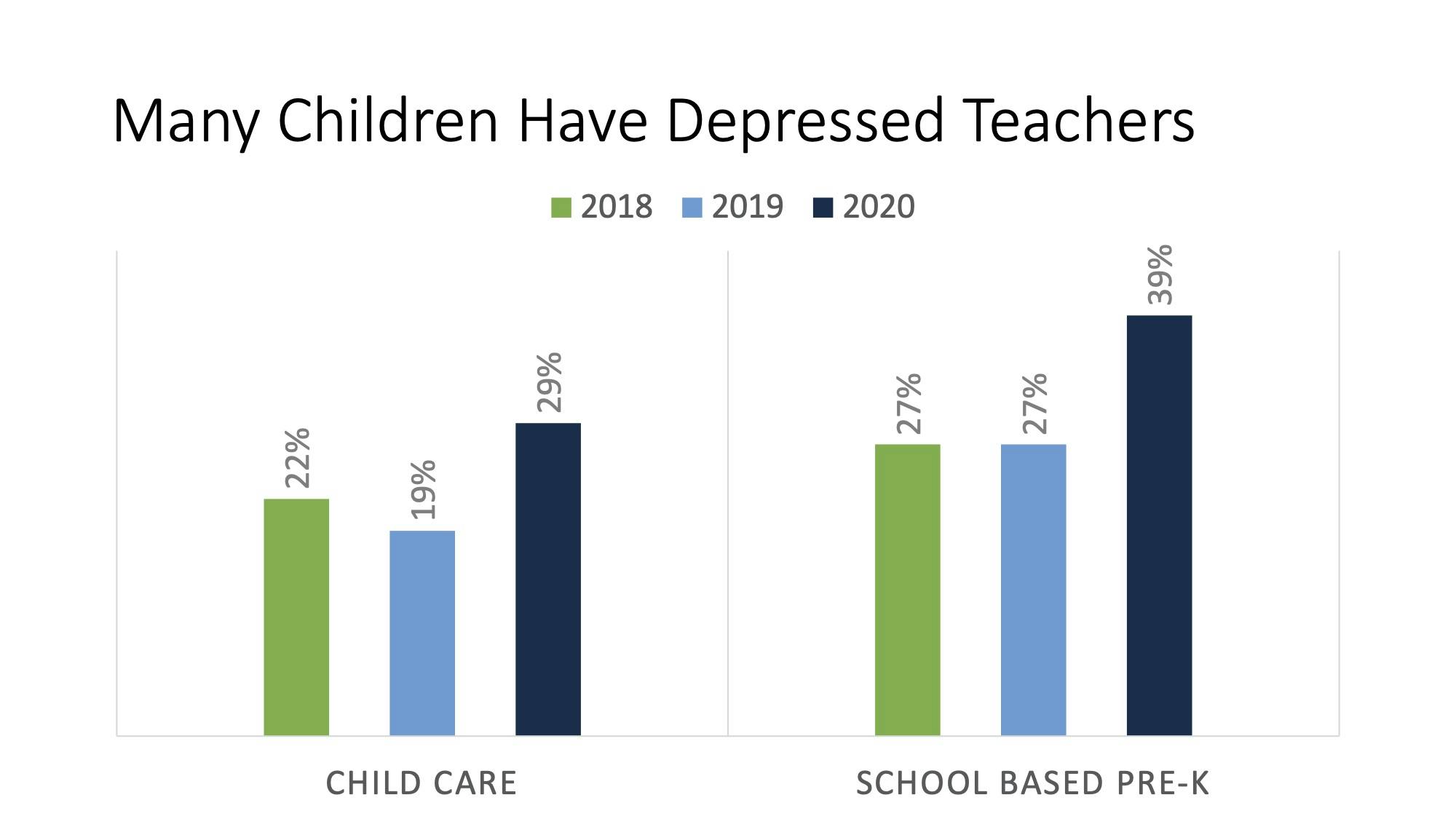

Many children have early education teachers who are depressed and who struggle with economic anxiety. Half of childcare teachers are food insecure, meaning they worry about having access to enough food to feed themselves or their families.

“The depression rates among these teachers are very high,” Markowitz said. “The low incomes they earn has a real impact on their daily wellbeing.”

Markowitz and her colleagues believe these high levels of stress and depression matter in the classroom and the experiences of children. Stressed caregivers are less effective. They may offer lower quality interactions with children and weaker teacher-child relationships, leading to increased problem behaviors for children.

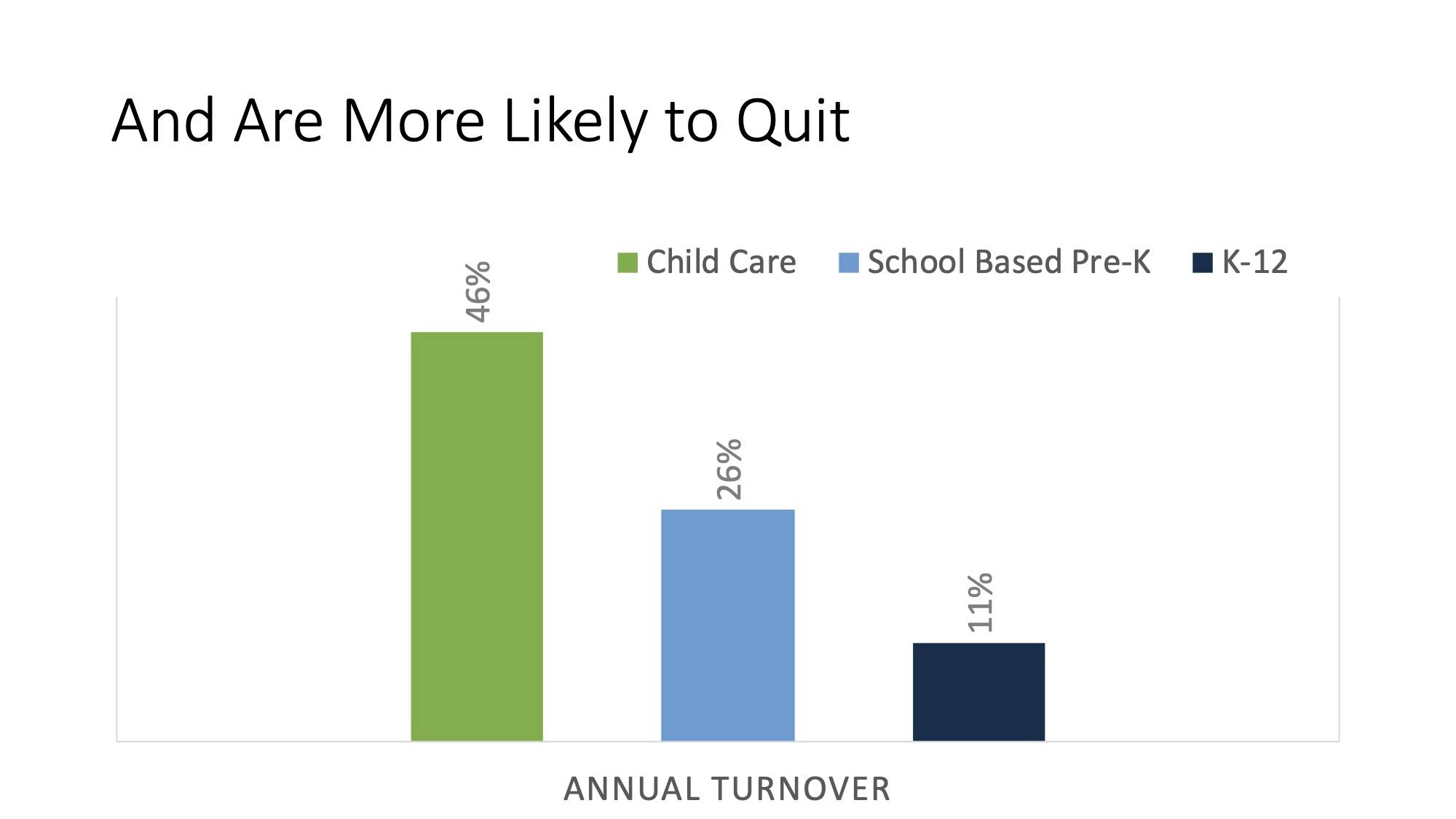

They are also more likely to quit. In the Louisiana study, nearly half of childcare teachers and a quarter of those working in pre-k settings left their jobs from one year to the next.

When teachers leave, child development suffers. An analysis of Head Start data by Markowitz shows that children whose caregivers leave showed less growth on measures of language, word and letter recognition, and early writing skills than those whose caregivers stayed. Their parents were also more likely to report their children had behavior problems.

To build a better system that meets the needs of children and parents, Markowitz contends we need to address the training and compensation of the early childhood education workforce.

As an example, she points to efforts underway in Louisiana to provide financial incentives for quality. They have established quality rating and improvement systems and offer refundable tax credits paid to both centers and teachers who provide high-quality interactions as measured by those systems. The program offers incentives of $3,300 to teachers.

“For many early education teachers, that’s about 10 to 15 percent of their salaries, an amount that can make a real difference in their lives,” Markowitz said.

Louisiana is also providing high-quality training opportunities for early childhood educators, including the establishment of an Early Childhood Ancillary Certificate. The program is free for teachers and those that complete the training are eligible to receive the states’ tax credits.

Established in 2014 the program in Louisiana has seen a dramatic increase in the quality of child care settings statewide.

“We need to look at the insights from psychology, about how children learn, about the primacy of relationships and interactions for young children, to build better early childhood education systems,” Markowitz concludes. “In educational policy, we need to ask what’s the right investment– what will get us the most bang for our buck, what will create opportunities for more efficient policy.

“Far and away the evidence suggests that children’s earliest years provide a powerful window for investment. It is the interactions children have with adult caregivers that do the most to build a strong foundation for learning. Smart investments in teachers offer a new vision for early learning, and have the potential to expand high-quality early childhood education, narrow opportunity gaps, and become a force for educational equity.”

The full presentation by Anna Markowitz is available at here.