The historic mid-century campus designed by Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander reflects the school’s commitment to learning, health, and well-being.

A historic model of pedagogical and architectural innovation, UCLA Lab School integrates its indoor and outdoor spaces to support learning, health, and well-being. Built in 1958 by mid-century modernists Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander, the campus provides an opportunity for UCLA researchers at CONNECT and design experts from the architectural firm Perkins Eastman, to study a learning environment that demonstrates the ability to adapt and be resilient in the face of climate disruption.

“I am thrilled by the ways UCLA Lab School is advancing research on how learning environments, including our unique outdoor spaces, influence teaching and student success,” says Christina Christie, Wasserman Dean of the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies. “Through a partnership with Perkins Eastman and the UCLA Lab School CONNECT research team, and with the active engagement of our teachers and students, we are deepening our understanding of how architectural and environmental design support learning.”

In 2022, the Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design brought together CONNECT researchers UCLA Professor of Education Megan Franke and Christine Lee with Perkins Eastman researchers Sean O’Donnell, Rebecca Milne, Emily Chmielewski, Heather Jauregui, and Widya Ramadhani. The collaborative examined the impacts of the school environment and occupant behaviors on thermal comfort, air quality, acoustics, and lighting, underscoring the relationship between learning and indoor environmental quality. This revealed how Neutra’s biorealistic design continues to provide flexible and comfortable indoor settings in support of inquiry-based and nature-based learning amid changing climate conditions.

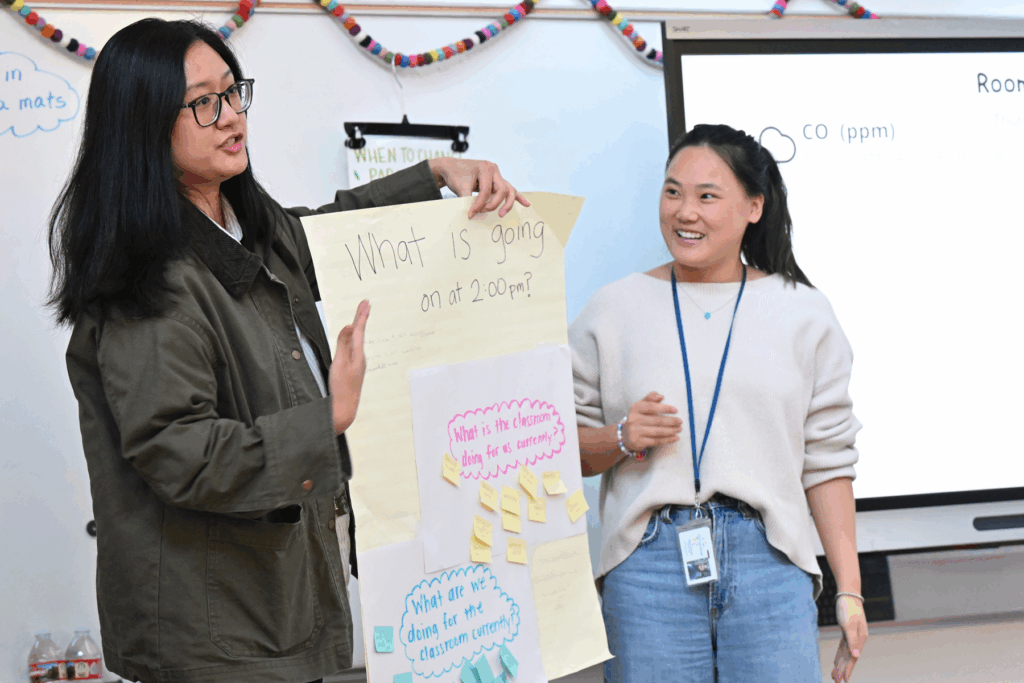

In order to best leverage the school’s architectural design to create healthy learning environments, the Perkins Eastman team came to Lab School to lead two working sessions with teachers and staff. Together they created a tool kit of strategies they could bring back to their classrooms to adapt with the changing climate. The working sessions helped Lab community members to strategize how to use mechanically ventilated resources, windows, blinds, and doors during different times of the day and seasons through a mixed-method approach, including digital modeling, climate projections, occupant questionnaires, classroom observations, and sensor measurements.

“This study underscores that learning and environment are inseparable,” says O’Donnell. “At the UCLA Lab School, every classroom has become a living laboratory for well-being, where teachers and students explore how the spaces they inhabit shape how they feel and learn. The insights gained here empower teachers, students, and designers everywhere to actively create healthier, more focused, and more inspiring places to learn.”

During the working sessions, the researchers recommended implementing behavioral and pedagogical strategies in the Lab School classrooms, including using full classroom spaces to disperse students in pairs or small groups to support better airflow; conducting the most physical activities in the morning or after the room has been unoccupied when CO2 levels are at their lowest; taking fresh air breaks outdoors or in other interior spaces that have less CO2 build-up; and conducting collaborative activities when students are in tighter configurations after fresh air breaks. In addition, teachers were encouraged to schedule classroom activities to take advantage of the time of day and the availability of natural light indoors, in order to balance temperature, create better airflow, provide needed exposure to sunlight, and limit CO2 levels.

The project, which is to continue throughout the school year, has already yielded results, including igniting a curiosity that UCLA Lab School students have taken upon themselves to address through inquiry.

Lee, who has conducted other studies at UCLA Lab School around environmental learning, says that providing the students with access to sensor data throughout the day has propelled them to asking research questions, starting when increased levels of CO2 were observed. She mounted air quality sensors in classrooms and gave access to the data to the students so that they could watch how CO2 levels fluctuated throughout the day.

“They [once] saw that the CO2 was at 1,000 and asked, ‘Is that bad?’” she says. “I said, ‘Let’s take a look,’ and sure enough, they figured out, ‘That’s bad. We need to do something about that.’

“It started with [opening] the windows and the doors It led them to go back to the data and see that [the levels] dropped when they did that,” says Lee. “That’s how it started. Now, there are asking advanced questions about, ‘Why do we care so much about CO2?’ ‘What does this even mean?’ By diving deep into the data, there are questions about investigating patterns. The kids have gone off now to research those questions.”

The pedological foundation of UCLA Lab School was established in Los Angeles in 1929 by founding principal Corrine A. Seeds, whose work was shaped by the teachings of educational reformer John Dewey. The school, then known as University Elementary School (UES), was moved to its permanent location on the UCLA campus in 1949, in a one-story building designed by Alexander. Between 1957 and 1958, Alexander and his colleague Neutra collaborated on the design of three additions to the campus, including a long, bar-shaped building; a set of four classrooms clustered around a central hall; and a series of three classrooms arranged in a “finger plan” fanning out from a curved corridor with courtyards in between.

Although the finger plan component was demolished in 1992, the remaining school buildings continue to preserve Neutra’s biorealism intent, incorporating natural ventilation and daylight and engaging the surrounding landscape as an extension of the indoor learning environment. Collaborating closely with Principal Seeds, Neutra and Alexander created a school with strong connections to nature, flexible learning environments, and spaces that encouraged children’s movement and exploration. The UCLA Lab School is a profound embodiment of Neutra’s philosophy of biorealism or biological realism, which he defined as, “the inherent and inseparable relationship between [people] and nature.”

A report, “Biorealism Today: Lessons Learned from Richard Neutra’s UCLA Lab School,” was released by Perkins Eastman in November, outlining the research project and its findings, delineating how the study underscores the importance of collaboration among architects, educators, and researchers in addressing challenges and developing solutions that integrate architectural and pedagogical strategies for optimal learning. The case study of UCLA Lab School provides evidence-based approaches that can be an example of the benefits of biorealism to other schools. The report offers guidance to educators, designers, and building operators on adapting both new and existing facilities to maintain effective teaching and learning.

Dean Christie says that the support of Raymond Neutra, president of the Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design, “[honors] his father Richard Neutra’s architectural legacy and highlights the enduring connection between thoughtful design and educational innovation.”

“This is an example of research-inspired design,” says Raymond Neutra, who visited UCLA Lab School in October. “The Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design endorses those who pursue practices like this in architecture. Perkins Eastman has been visiting their designed buildings after completion to see what they can learn for future projects.

“We asked the Perkins Eastman team and researchers at the Neutra and Alexander-designed 1959 UCLA Lab School if they would like to do a post- occupancy evaluation at the historic indoor-outdoor school, even if it was 66 years late. They said yes, and now we have the report.”

“We hope this study sparks broader dialogue on how architecture, nature, and behavior intersect to support learning,” says Ramadhani, a co-author of the report. “By revealing how indoor environmental quality affects cognition and comfort, it offers practical guidance to create more adaptive, resilient, and human-centered schools.”

“Perkins Eastman has a long history of evidence-based design research, particularly in healthcare, workplace, and educational settings,” says Milne. “While this study is unique in its combination of pedagogy, indoor environmental quality, and biorealism in a K–12 context, it builds on our broader commitment to understanding how the built environment influences human behavior, well-being, and performance.”

Lorrie Cariaga, a teacher at UCLA Lab School, says that the study has propelled her students to make several changes to their routines – as well as that of their parents – and that after a month into the study, they became “obsessed” with monitoring the CO2 levels in her classroom, asking for extra time during classes to discuss new strategies to maintain an optimum learning environment, such as finding out what types of plants would be beneficial to reducing CO2 in their classroom and in the Lab School’s greenhouse.

“They are like mini weather reporters, because at any given time during the day, they’re reporting the CO2 levels, the noise level,” says Cariaga. “I have students who are telling their parents to open up the windows in the morning to let the stale air out. It’s just fascinating how they’re making those environmental changes based on these little sensors that came into our classrooms.

“They’ve learned that 540 [PPM] is the optimum number for brain function and cognitive abilities,” she says. “It’s when you have the most energy – they’re not tired, they’re not sluggish. When we [were going to] take our math test, it was high… at 800 [PPM]. They didn’t want to take the test until we got the numbers [down]. We put the fan on, opened the windows, and did some breathwork and it lowered it down. And then we took [the test].”