A study finds that LA County’s charter schools are underreporting and providing less than adequate resources to assist its student homeless population.

Charter Schools in Los Angeles County serve a significantly lower proportion of homeless students than non-charter schools. Yet those students are more likely to be chronically absent and graduate at substantially lower rates than their peers who attend public schools according to a published report by the UCLA Black Male Institute at the School of Education and Information Studies. Their research analyzing data from the 2018–19 school year found that there were, amongst other key findings, significant racial disparities especially among “Black students who have the highest absentee rates and the lowest graduation rate of any other racial group of students in the charter schools,” according to Elianny Edwards. They also show that charter schools drastically undercount the number of homeless attending their schools, partially due to a lack of well-trained homeless liaisons. Homeless experts agree that 10 percent of economically disadvantaged students experience homelessness. The Federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act mandates that a homeless liaison be on staff to handle this vulnerable population, yet too often the role is left to charter network leadership and school administrators, many too busy or ill-trained to handle the maze of details of working with these students and their families that are in crisis.

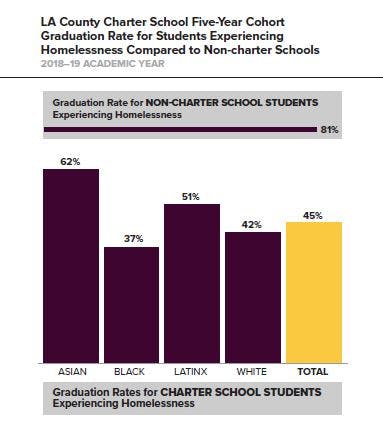

The Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) is home to 600,000 K–12 students and its charter school enrollment is around 252,000. The homeless population for the entire system has averaged approximately 5 percent of the total enrollment. There are more than 4,000 homeless students attending Los Angeles County charter schools, a figure that represents nearly 7 percent of the total LA County K–12 (charter and non-charter public) enrollment that has been identified as homeless. The UCLA Black Male Institute analyzed data between 2016 and 2019 and found that charter schools in Los Angeles County were reporting serving a lower percentage of homeless students than non-charter public schools, yet those students had a higher absentee rate and lower graduation rates, especially amongst Black students. Forty percent of high school students experiencing homelessness in the charter schools had missed more than 18 instructional days as of 2018–19. In the same period analyzed, the charter school homeless population was reported to be approximately 2 percent of its student population. The five-year cohort graduation rates showed that charter school students experiencing homelessness were graduating at a rate of 45 percent, which was 35 percent less than a similar population in non-charter public schools. Black homeless students were a particularly vulnerable, underserved population: 50 percent of these students were chronically absent, resulting in missing more than 10 percent of the school year, a differential between the other racial and ethnic groups of 80 percent.

“Black students have the highest absentee rates and the lowest graduation rate of any other racial group of students in the charter schools.”

The Federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act requires local school districts to provide support in the form of a district liaison that would provide assistance in the schools identifying students that are in crisis due to homeless-ness and provide the necessary support. The Act defines homelessness as anyone who is living in shelters, vehicles, motels or who share housing with others due to economic hardship, or residing in accommodations not initially intended as living or sleeping quarters. It requires that all public schools provide these students with basic needs such as transportation to and from school, school supplies and food service. An audit released in 2019 by the State of California on Local Educational Agencies (LEAs)—school districts, charter schools and county offices of education—found that, amongst other deficiencies, LEAs “are not providing adequate services, that could better ensure the success of these youth.” (CA State Audit 2019).

Yet, data has shown that when LEAs provide the requisite means, including a homeless liaison and support necessary for a student to graduate with a high school diploma, it reduced the chance that as an adult they would become homeless. McKinney-Vento does not specifically require that a school homeless liaison be full time but stipulates only that “appointed personnel have the capacity to fulfill all of the time-intensive responsibilities the position requires.” The report looked at the breakdown of personnel handling these student/family services in 235 charter schools in LA County. Homeless liaisons were more likely to be principals or district executive leaders who would then often assign the role to operations staff that have little student or family interaction training. The top two job titles doing the work of a homeless liaison were principals (33 percent) and business managers (20 percent). Parent and community engagement staff accounted for 20 percent and social workers only 10 percent. A further breakdown of these schools, analyzed for the 2019–20 school year, revealed that principals and vice principals, operations managers and chief operation officers—even office managers—were identified as homeless liaisons at least 136 times, a frequency of nearly 60 percent. Staff that had the appropriate training in working with these vulnerable students, including parent engagement specialists, counselors and directors of students and family services were engaged just 31 times or 13 percent. According to Earl Edwards, “a third of the schools we analyzed designated this position to their school leader—an already busy and demanding position. If the homelessness liaison cannot fulfill their responsibilities, students experiencing homelessness are likely to be unidentified and underserved.”

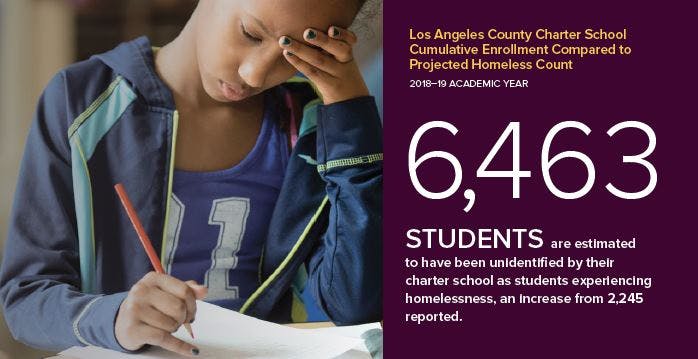

The research also cites a huge discrepancy in the reported homeless students in LAUSD charter schools in 2018–19 which could also be indicators of the lack of well-trained staff that are able to identify students who fall into this category. An audit of 180 of 269 operational charter schools shows that the student homeless population may have been undercounted by over 6,400 students, when using the 10 percent benchmark as defined by McKinney-Vento. Hence, of the county’s economically disadvantaged students (in this instance, 87,083), LA County charter schools’ actual count would have increased from 2,245 reported to a projected 8,708. The research collected on these 180 LAUSD charter schools maintains that over 80 percent of the student body is economically disadvantaged. Yet, charters reported that in 105 of the 180, less than 1 percent of their students experienced homelessness.

As the charter school system has grown in LA County there has been a consolidation of administrative services within the larger network of charter schools. The logic behind this shared centralized service was to provide consistent messaging and operations to better streamline common support to all schools within their networks and maintain a unified set of procedures (these are referred to as Charter School Networks). One type of shared service would include student/parent handbooks and website templates as a one-stop source for all information on each school’s offerings. Yet when the institute reviewed 15 of the largest charter school networks in LA County they found that only two schools listed the educational rights of students experiencing homelessness on their school websites. It also found that five of the fifteen network schools mentioned the education rights of families experiencing homelessness in their family/student handbooks. A little more than half referenced McKinney-Vento. They also found at least four charter school networks that did not provide reference to any resources and that several homeless liaisons were not even listed. This lack of access to distributed materials both as online resources or in school policy handbooks created barriers for “self-advocacy to disclosing their homeless status.” Birmingham Community Charter was specifically cited in the State Auditor’s report as being negligent in not including this information. Since then, Birmingham has revised its responsibilities on its website for any and all homeless youth and their families (Birmingham Community Charter High School), in both English and Spanish.

“Of the charter schools analyzed for the 2019–20 school year, principals and vice principals, operations managers—even office managers—were identified as homeless liaisons.”

MOVING FORWARD

There are many recommendations that the report has concluded would greatly improve the effectiveness in supporting vulnerable student populations in the charter schools and charter school networks.

- Accountability, starting with the installation of a highly trained homeless liaison would best be able to engender trust in building relationships with families in order to advise and advocate on their behalf.

- Audits of a school’s homeless population should be done twice a year to better provide a benchmark to offset the possible issue of miscounting. If the homeless population falls below the benchmark, the homeless liaisons would then be required to provide data to rationalize their numbers being so low. The authors believe that the audit process “ensures that all kids experiencing homelessness at the school are being identified and served.” The California State Auditor’s Office made a similar recommendation in their report.

- All charter schools should be required to “explicitly state the educational rights of students experiencing homelessness.” Schools or their networks should be identified and held accountable if they do not provide this critical information.

- Finally, a support team, led by the homeless liaison and including teachers, counselors, parents, county departments, community partners and other school personnel should be created to analyze and advise on the necessary resources to meet the specific needs of families and students experiencing homelessness at each respective school in order to ensure that these students can be supported for success.

“The success of public schools is often measured in part by graduation and attendance rates, even among those students experiencing the very real challenges of homelessness. The same measures should be applied to the evaluation of charter schools. They need to do more and better in serving students experiencing homelessness.”

The Los Angeles Times reported in March 2019 that the LAUSD, the nation’s second-largest school district, has an entire division that oversees the charters, both new and existing, and has been lauded as being one of the state’s most “robust monitors.” Still at the local level those responsible for oversight include very small school districts with minimal staff and underfunded resources, that are unable to be effective monitors on behalf of all students, let alone homeless ones (Los Angeles Times). According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, more people in California experience homelessness than in any other state in the nation. At the same time, according to available data, California LEAs are not doing enough to identify youth experiencing homelessness (CA State Audit 2019). With the overall number of charter schools in California growing (at least 1,300 as of 2019), the core mission of all schools cannot be more critical for educating students. Tyrone Howard, UCLA Education professor and co-author of the institute’s report, says, “The success of public schools is often measured in part by graduation and attendance rates, even among those students experiencing the very real challenges of homelessness. The same measures should be applied to the evaluation of charter schools. They need to do more and better in serving students experiencing homelessness.

Key findings:

- In LA County charter schools, the five-year cohort graduation rate for charter school students experiencing homelessness is 45 percent, approximately 35 percentage points lower than the graduation rate for students experiencing homelessness in non-charter, public schools.

- Forty percent of high school students experiencing homelessness in LA county charter schools were chronically absent and missed 18 or more instructional days in the 2018–19 school year. Moreover, one out of every two Black high school students experiencing homelessness were chronically absent.

- The homeless liaison is the most important role in supporting students experiencing homelessness as defined by the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. In LA County charter schools, this role is often designated to network leadership and school administrators.

- Homelessness experts assert that typically 10 percent of economically disadvantaged students experience homelessness. Employing a 10 percent benchmark in LA county charter schools suggests that in 2018–19 potentially 6,463 students experiencing homelessness were not identified or served.

- To ensure that students experiencing homelessness are identified and supported in charter schools, it is critical that schools implement student audits twice a year using a 10 percent benchmark to identify potential undercounting. Further, schools must designate a homeless liaison capable of fully executing the federal mandates of the position and serving as head of a larger student support team.

Link to full report: https://blackmaleinstitute.org/unseen-and-unsupported/

This article is part of the UCLA Ed&IS Magazine Summer 2021 Issue. To read the full issue click here.