SEIS alumnus and executive director of the California Mathematics Project oversees K-12 teaching and learning across the state, discusses potential of the new California Mathematics Framework.

For the last 11 years, Kyndall Brown (’09, Ph.D., Education) has served as executive director of the California Mathematics Project, a statewide network of providers of professional development for K-12 teachers of mathematics. It is fitting that Brown’s current post has historically been based at the UCLA School of Education & Information Studies, enhanced by the expertise of faculty and researchers at the UCLA Mathematics Project.

While still a classroom math teacher, Brown attended the UCLA Mathematics Project Summer Leadership Institute, which led him to contribute more broadly to the teaching of mathematics across California. He was recently involved in the creation of the new California Mathematics Framework and will be instrumental in its implementation across K-12.

Brown previously served as a researcher and teacher educator for the UCLA Mathematics Project at Center X. He achieved his master of arts degree in mathematics education and his teaching credential at CSU Dominguez Hills. Brown is the co-author of “Choosing to See: A Framework for Equity in the Math Classroom.”

How did you contribute to the new California Mathematics Framework?

In July of this year, the State Board of Education approved the new California Mathematics framework. I was involved in a group of folks organized to give feedback on the second draft of the framework, and I did write a snapshot which is an example of mathematics teaching, and that ended up being included in the final version. I’m going to be actively involved in supporting the implementation of the framework. My understanding is that they’ve posted all the edits from the last revision and they’re good to go. Right now, publishers are trying to think about how they’re going to align their materials with the new framework.

From a statewide perspective, how can educators and administrators best prepare themselves to implement the new framework? What would you urge them to do?

I would urge them to read the framework, but I know that’s asking a lot. It’s 1,000 pages, so they need to think, pick, and choose, and most teachers usually don’t read the framework. I would want them to read chapters one and two, and then there are grade level- specific chapters, so they definitely need to look at the chapter related to their specific grade level. They also need to get together with other teachers at their school. If they belong to any math ed organizations, they need to be forming study groups [and] to begin to collaborate with their colleagues, to really think about what it’s going to mean to change their instruction, to align to what the framework is asking [of them].

How would you allay any fears that this could shortchange students who are aspiring to, or in advanced levels of math learning?

There is nothing in the framework that would make make any changes to the access that students had, to advancing in mathematics. There’s a lot of misconceptions out there about the framework, and a lot of misinformation that’s been put out. But there are no changes in the framework that would stop someone from taking whatever courses they wanted or needed to take.

How will the framework give a leg up to those students who are not at advanced levels, from those who are struggling, to those with average math ability?

It’s about thinking about teaching in a different way. In the previous frameworks, the focus was on standards – really, since the 1997 framework, which was the first framework that laid out of the topics that a teacher was supposed to teach at their grade level.

Teachers have these lists of standards, without any real guidance as to how are all these standards interconnected, [such as] what are the most important standards to teach and how they are connected to other ideas in mathematics. Usually, they just followed along the sequence of the textbook, starting with chapter one.

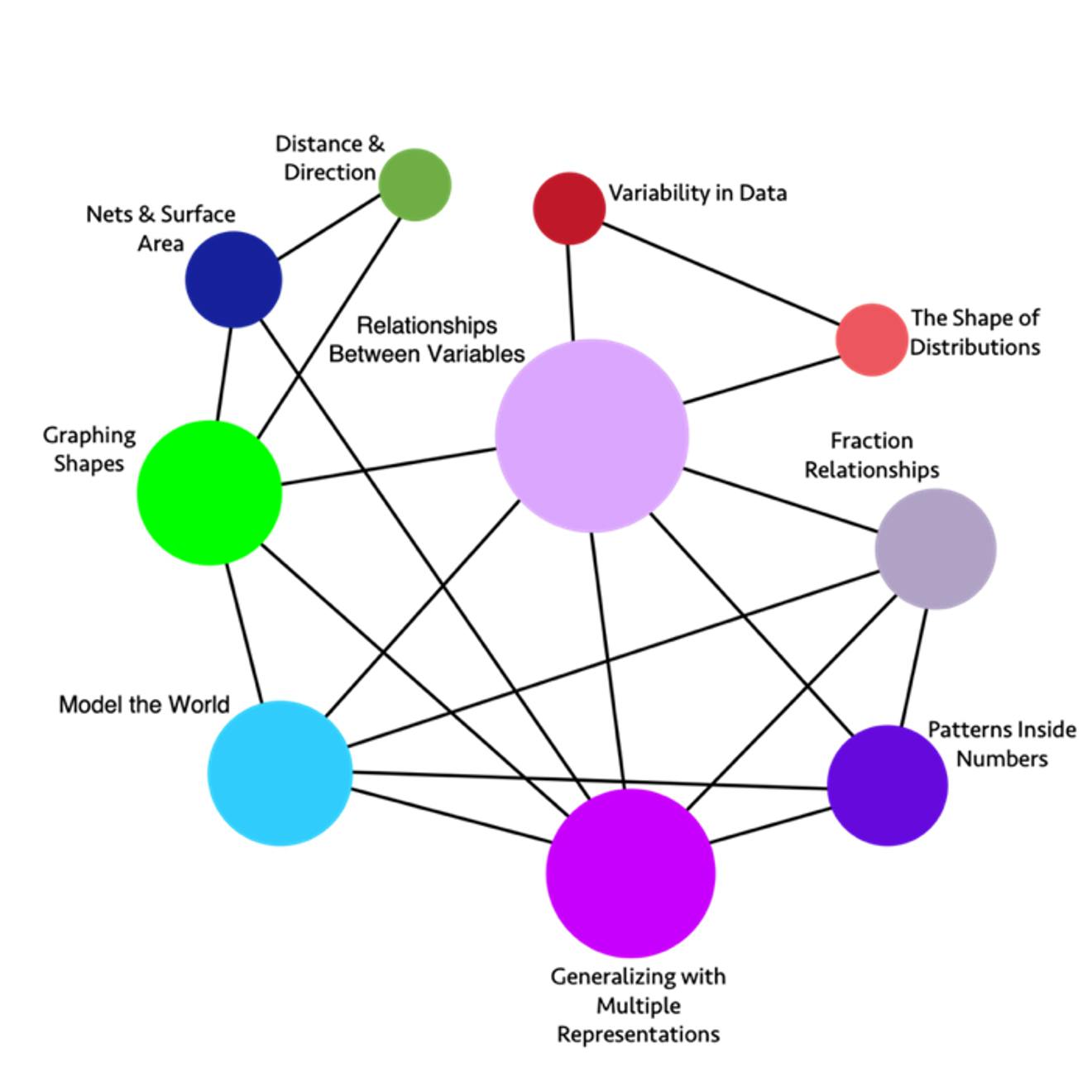

This new framework is reframing that and talking about what are the big and most important ideas in each grade level. And so, in the framework they have created these visual images. For each grade level, [the framework] has these nodes. The larger the node, the more emphasis [that] should be placed on that particular idea or concept. The lines in between show relationships between the big ideas. This gives teachers a much more coherent plan around how these different ideas are connected to one another and what [they] need to place more emphasis on, as opposed to less emphasis. And so that’s one way the [new] framework is different.

In the 2013 framework, or in the Common Core era, the framework introduced the Standards for Mathematical Practice [which] described how students should be engaging in mathematics. (link to visual of Standards) Teachers have been talking about them using them and we’ve been doing professional development around them since 2013.

What the new framework has [added] are the Drivers of Investigation to talk about the why – the forever question in math is “why do I need to know this?” The tasks that we have students engaging in should be helping them to make sense of the world; predict what could happen; and [understand] affect, or impact on the future. And then, the Content Connections are the what. There are four Content Connections: reasoning with data; exploring changing quantities; taking wholes apart and putting parts together; and discovering shape and space.

One of these three drivers should be the focus of whatever tasks you’re engaging students in. This is hopefully bringing a lot more coherence to the work and helping teachers make those connections for themselves and for the students.

How often are math standards reviewed?

The first standards were [created] in 1997. In 2013, the Common Core standards came along and kind of refined them. You get fewer standards at each grade level, and then, once the standard is hit, it [isn’t] revisited over and over again. That’s the idea of the framework, that every seven years we would revisit it but they didn’t choose to change any standards in this framework, the standards are the same.

Will they eventually change?

They’re not going to change. Again, hopefully, with teachers looking at what the big ideas are, they’ll be able to focus on those standards that are the most important, where they should be putting most of their emphasis.

At all grade levels, teachers tend to teach what they like to teach. They have their favorite things to teach as opposed to what’s necessarily standards or grade level-aligned. It’s important that the teachers know the standards to them figure out what’s grade level-aligned, but now they’re really going to be able to understand what are the most important concepts their students need to master at each grade level and how are [the concepts are] connected to the other big ideas.

Will this affect frameworks for teaching math across the nation?

Probably not. It will probably influence textbooks, because publishers are going to be writing curricula specifically to these standards. I can imagine other states might adopt some of these curricula as well. But I don’t think it will [affect] all. Education is a state-by-state thing.

What prompted this change overall?

It’s mandated every seven years that the framework be revisited and be updated, so statute is one of the reasons. But again, we’ve been on this path since the Common Core to really focus on student understanding, reasoning, and problem solving. And, this framework took a strong stance towards access and equity as well.

What propelled you to transforming math education?

I began my career as a classroom teacher, and I taught for 13 years at both the middle and high school level. About nine years into my teaching career, I attended the UCLA Math Project Summer Leadership Institute and everything changed. It changed the way I taught, and got me involved in leadership in math education. It was kind of a natural progression and from there, I started getting involved in teacher education.

After being able to observe math education on both statewide and national levels, what do you think are some of the biggest issues in math education right now?

There has always been a shortage of qualified teachers [in] low- performing urban schools, the entire time I’ve been in education [and] now, it’s hitting more affluent schools. But there is still a huge problem in the most economically impacted communities [with] stability in terms of teaching, and particularly with math. I can think of some middle schools where there are no permanent math teachers. There are long-term subs, which means they’re only there for a certain amount of time before they have to leave and be replaced by somebody else.

When you have that kind of situation, there’s no stability, there’s no consistency. And if that happens three years in a row, it’s very unlikely that the student is going to enter high school ready to do college preparatory mathematics. So, we need a stable work force, and particularly in the most heavily impacted schools.

Literature and humanities can be a hotbed of controversy in teaching, but how is the teaching of math affected?

A huge part of math is solving problems, and if it’s a real world problem, then it has to have some context. There has been a huge push towards culturally relevant and responsive pedagogy, and so problems should reflect the realities or students lives. At the lower levels, it’s not that big of an issue, because [within] the nature of the math that they’re doing, you can cover [material] with lots of context that are very benign, not controversial. We’re talking about fractions, you can have them divide up food, anything.

As you start to get into the higher grades, most of the context you see for math problems are military, industrial, or [financially-related]. They just as easily could be about social issues. There has been a movement since around 2005 to incorporate social justice into mathematics classrooms. Not all topics can be taught using a social justice context, but a lot can, particularly at the middle school level. If you’re talking about the strand of statistics and probability, students can collect data about anything. So, why not collect data about things that are important to their lives?

But there’s a pushback. There are people who feel like math should be neutral, that it shouldn’t involve any kind of social context, even though it does. If you’re talking about the the path of a missile, that’s a context. And you’ll see that oftentimes in a math class when they’re talking about quadratic functions and parabolas.

There have been a number of books that have come out in the last few years, focusing on social justice tasks at different grade levels. One is called, “Do Postal Codes Predict Test Scores?” They use a GIS map, an interactive map that has laid out all of the different census tracts in, let’s say, the state of California. So, it has all this data about median income, parental education level, median household value, things like that. But, it also has on it the high schools in each area, and their SAT or ACT scores. The students then can collect data where they compare SAT score and household income. There are all these different factors that they can analyze it by, and then they create a scatter plot. They create a line of best fit, which is an algebraic equation, and then they interpret it in the context of the problem.

What the data is likely going to show is the higher the median income, the higher the SAT and ACT scores. You’re teaching them about slope, y- intercept, algebraic functions, but it has a context around social justice that causes them to think, “Okay, what does the SAT or ACT really measure?” So it’s raising social and political consciousness and at the same time, it’s showing them that math can be used for these purposes, that math can be used as a tool for liberation.

In Chapter Two of the framework, which is Teaching for Equity and Engagement, it talks about five components of equitable and engaging teaching for all students. The components are plan teaching around big ideas; use open engaging tasks; teach towards social justice; provide student questions and conjectures; and prioritize reasoning and justification. So, teaching towards social justice is one of the components that the framework identifies as equitable, engaging teaching for all students.

How do you hope this new framework and any other measures like it, will help to shape a new generation of math educators, as well as people in positions like yourself that can help push change from a bigger perspective?

I’m hoping that it will influence professional development of in-service teachers; that it will influence the preparation of pre-service teachers; that it will influence the curriculum that gets created so that teachers will have the instructional resources to implement the framework.

There is going to have to be an investment in professional development, there’s no two ways around it. We’re not going to see change unless teachers really have an opportunity to spend time, like I said before, collaborating with one another to make sense of what the framework is asking for; thinking about, “What does it look like in my classroom, for my students?”’ and getting the support that they need to experiment and try things out. And I hope people don’t think that the fact that a new framework was created, that in and of itself means that there’s going to be change. It’s not. There have to be some real money resources put behind this for it to work.

At this point, do you see most districts buying in, or is it too soon to tell?

There is this quasi- governmental organization called the California Collaborative for Excellence in Education. They made this $50 million grant available that will be divided amongst the 58 county offices of education in California, a math science and computer science grant. And so, county offices have four years to spend the money. They’re in the process right now of doing asset mapping in their regions, creating action plans. The hope is that a lot of this money will be used to support framework implementation. I also heard that Superintendent Thurman is trying to propose legislation specifically for mathematics professional development, so I’m hoping that will work out as well.

How did your education at UCLA prepare you for an opportunity to lead math education in the state of California?

Going to the UCLA Math Project was a pathway to graduate school. The person who preceded me in my current position, Dr. Susie Hakansson was at the time, the site director of the UCLA Math Project. She really was the one who nurtured my leadership, and there were so many other people. I was working here, and then this NSF grant called Diversity in Math Education became available [and provided] a full ride. It was real easy to do, working for the Math Project, being here on campus, having Megan Franke as my advisor, who at that time was the director of Center X, and so it was easy to connect with her and interact with her and get her support [for the] math ed focus of my dissertation.

What inspired your recent book, “Choosing to See: A Framework for Equity in the Math Classroom”?

My co-author Pamela Seda and I wanted to really share what does equity mean in a math classroom or what does culturally relevant pedagogy look like in a math classroom. In a language arts classroom, I can have students read literature that reflects the cultures that they come from. In social studies class, I can have them study [those] cultures.

What we wanted to do is to pull together all the resources from over the years, because she has about as much experience as I have. What are the resources that teachers can use to make their math classrooms more equitable? As as part of her dissertation, she came up with a framework called the ICU CARE framework. Each letter stands for one of the principles: include others as experts; be critically conscious; understand your students well; use culturally relevant curricula; assess, activate and build on prior knowledge; release, control, and inspect. For each one of those principles, there’s a chapter in the book. We talk about what the principle is about, why it’s equitable, and what happens when you don’t engage in that principle, as well as sample activities of what [teachers] can do.