Professor Marjorie Orellana and doctoral students share their findings in the Harvard Educational Review.

While much of the educational press is focused on learning loss during the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic, Marjorie Faulstich Orellana, UCLA professor of education, along with postdoctoral researcher Lu (Priscilla) Liu (’20, Ph.D, Social Research Methodology) and graduate student Sophia L. Ángeles (’22, Ph.D., Urban Schooling) have conducted research that reveals the ways that students and families have actually gained knowledge beyond academics, during periods of lockdown and exclusively remote learning.

Results from their “ethnographically-oriented,” diary-based study, published in the fall issue of the Harvard Educational Review, analyzes the learning experiences expressed in the diaries of 35 families from diverse ethnicities/races, cultures, national origins, and social classes across the United States. Identifying common themes that emerged, the researchers explored the ways that families reorganized their daily lives and reinvented themselves during this unprecedented time, centering their cultural heritage, creativity, health, well-being, and connections to nature and to others. The study also reveals how families used technology in creative and innovative ways.

Countering the current focus on pandemic learning loss, their study serves to begin the conversation for reimagining education in culturally sustaining ways.

How did you choose the families you studied?

Marjorie Orellana: We worked very hard to secure a diverse set of families. We began by casting a net widely to all our social networks. It was all happening very quickly, and we needed to jump on it. That meant including families who would be willing to participate in an ongoing reflection on their pandemic experiences. It was as a time of great instability – many people didn’t know what was going to unfold.

We principally looked at three “buckets” – three types of families, based on the relationship of families to the pandemic and how families of young children were likely to be impacted. The three categories were (1) families who lost work during the pandemic, (2) parents who were going to be working at home while their children were at home, and (3) essential workers. And then, within each of these three categories, we wanted racial, cultural, ethnic, linguistic diversity, and some degree of geographical diversity.

We knew that some families were going to be impacted economically by losing work because of the pandemic. We knew that some people were going to feel increased stress because of working at home while caring for children at home, and we knew that some people were going to be feeling physically health-stressed by having to go out to essential jobs. It was their relationship to the economy and family life that we were trying to capture, and then in turn to ask how this impacted their family life and learning.

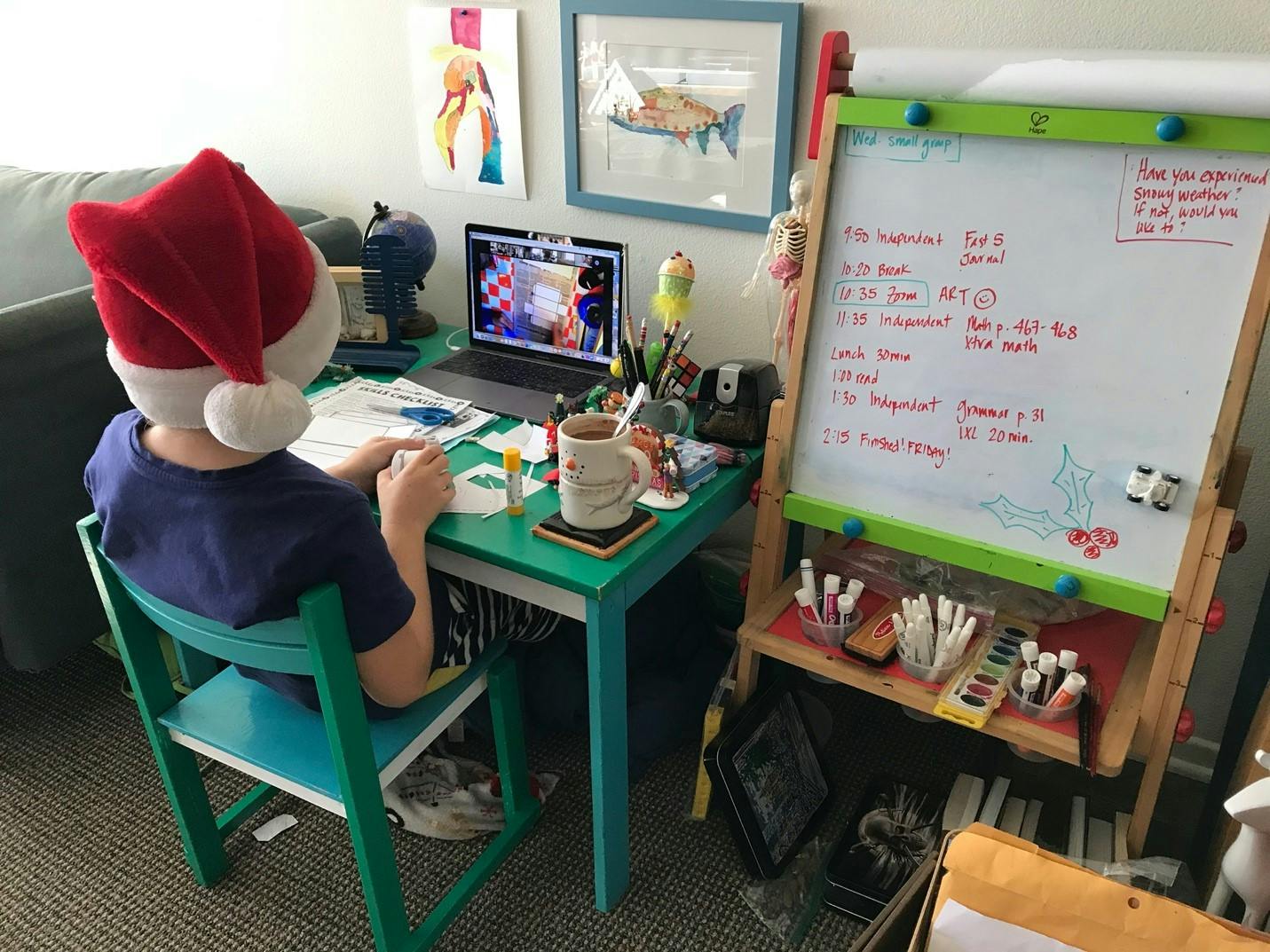

Courtesy of the Garduño Family, Chicago, Illinois

How did the economic impact play out among your research subjects’ ability to cope?

Marjorie Orellana: We had families from widely varying income levels, different relationships to a work, economy, and family life, and from different racial, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic groups. We saw that people were impacted in many different ways, and yes, economics mattered for the resources families could draw.

Those impacts were very real stressors – economic stresses, psychological, emotional, physical concerns about health, and more. We know that a great deal of public attention has gone to those things and has gone to learning loss as measured by test scores and as measured by traditional accounts. We do not diminish that at all.

At the same time, our offering is to say that by talking with families, listening to them, hearing their experiences through the pandemic … we see that, families learned a lot of things, they have a lot to say. They drew their own conclusions about what they value in terms of education and cultural process for their children and they enacted that in the choices they made.

And that even includes technology. Yes, families were initially impacted by not having access to high-speed internet, and yet schools, to varying degrees, managed to get iPads into kids’ hands. So, kids learned a lot about technology that we could build on, going forward.

What was the income range of the families you studied?

Priscilla Liu: We recruited 35 families in total, and eight of them self-reported that their household income was less than $25K; five as $25-49K; and nine as $50 to $99K. The rest were beyond $100K.

I also wanted to build upon what Marjorie said about this inequitable access to technology. Yes, there are families, who have an annual income below $25K, they still get iPads from the schools, and the kids were actually trying to figure out, in that situation, how to use the technology creatively. So, we are not talking about the inequitable distribution of technology or access to internet. In this paper, we are talking about how children with limited resources are being creative and the parents are supporting them, facilitating this learning process.

What were some of the most common themes that emerged from how these families managed to thrive amid the pandemic?

Sophia L. Ángeles: We identified different themes, but the findings all relate to how families were learning together, spending time together, whether it was engaging in the sharing of a cultural exchange, language or cooking. We also highlight how families took time to engage in self-care: how they attended to their physical, spiritual, and mental health. For example there was one family that that we highlight that engaged in a family night, around games, movies, and food.

Spending time with family was a very big theme, and we document many different variations of how families were doing this, the activities that they were engaged in, and the learning that was happening. For example, one household in the Central Valley used Zoom to help their children learn Hindi with their grandparents. Many of our families are part of transnational families and took advantage of digital tools to talk to family in Mexico, Guatemala, Italy or China. We offer these different variations of what it meant to be together.

I’m guessing that a lot of these families – pre-pandemic – didn’t have that kind of time to engage in family time. Do you want to comment on that?

Marjorie Orellana: Elinor Ochs’ book on a Sloan Center study in the early 2000s, which is a study of middle-class family lives, reports on the tremendous stressors families felt – that they didn’t have enough time together. They lived super-scheduled lives. They didn’t have much time under the same roof at all. There were tensions over the stresses of homework when it entered the home and stresses over the division of labor for household tasks.

So, it’s very interesting to see the experiences of our families, 20 years later, and to put them in dialogue with the Sloan Center study, to see how the pandemic shifted family life. For some families, those stresses increased as [they] were still trying to get out the door and go to essential jobs. For others, it decreased, and they had more time together under [one] roof.

We’re trying to bring all of these lessons into the future, not to just say, okay, the pandemic is over, we’re back to normal. We know that something very profound happened during those two years to each of us individually, and to us in our families and household units.

Courtesy of the Blanco Family, Los Angeles, California

Since the study, what strikes you as families begin to go back into their regular routines of work and school out in the world?

Marjorie Orellana: I’m most struck by the fact that in very few spheres do I hear people really taking a pause to say, “Can we reflect on what we all just went through, and what we learned from it?” There seems to be this rush to get back to normal and speed up and get the kids caught up [on] all that they left behind.

Sophia L. Ángeles: From this study, we learned that multigenerational households are rich with resources whether that be cultural, linguistic, or human. I hope that we are able to recognize these types of households in a more positive light moving forward.

Priscilla Liu: I am struck by how families with international ties perceived and coped with the pandemic differently, because they received information from overseas, and interpreted it and implemented the family-level “policies” in their own ways. For instance, in the U.S. the dominant narrative is that the pandemic is over and we can go back to the regular routine of work and school; however, in some countries there are still strict policies and mandates on COVID, so some of our families still follow these rules and ask their children to wear masks even when they go back to school in person now.

What were the sentiments around learning loss among the families you studied?

Marjorie Orellana: Families expressed a variety of concerns to us, and certainly some families were worried about the setback for their children. The middle-class families, or more educated parents in our households, seemed more concerned about that. What we’ve heard families say more of – more than talk about learning loss – was, they see their kids are more relaxed now. They’re less stressed. They valued having the time to connect as families. Learning loss wasn’t at the top of families’ radars.

They were concerned about health. They were concerned about safety. They were concerned about wellbeing. They were concerned about mental health. They were concerned about the stressors on them as they juggled and managed these things, and sure, a little concern about how they could play a role in having their kids keep up with the demands of school as it was put on to Zoom.

Priscilla Liu: I echo what Marjorie just said, and also, from our paper, we wanted to tell the world that we recognize the learning loss but wanted to show what was gained, and to expand how we understand learning. It’s not just about learning school curriculum. It’s about the everyday practices. Children acquire knowledge, social rules, heritage, culture, and language through these everyday routine activities.

On top of that, we also wanted to show the world that both parents and children learned a lot of life lessons. That’s something unique about our project. Some teenagers wrote stories and diaries [expressing] that they learned to be empathetic. They learned to be grateful. They learned how to help others within their communities, across different families. We were actually very surprised to see that from the teenagers’ journals, and they reflected wisdom beyond their age. That’s what we want to tell the world – that on top of the loss, we also have some positive lessons.

Courtesy of the Buttermiller Family, Los Angeles, California

Marjorie Orellana: We’re not trying to brush under the rug the very real concerns. We just feel that we’re not really listening to families if we only focus on learning loss, because that’s not what they’re telling us. There was one highly educated mother who was concerned that her son might experience some learning loss, but she also marveled at his creativity that was flourishing during this time, and she quoted him her son as saying, “I love COVID, because we have time to be creative.”

Sophia L. Ángeles: It was very interesting to see what they were learning as the pandemic was unfolding across the world, including how they made sense of how we as a society take care of each other.

Do you offer suggestions in the paper for how schools can do that?

Marjorie Orellana: Basically, we suggest doing what we did in this study: talking with and listening to families. We can ask, “How did you experience this. What did you do? What did you learn? What was some new skills you acquired?” Then, we can see how schools could create more space for sustaining those practices and skills.

We know this was a profound experience, and it affected people in lots of ways, including mental health and stress. We’re just saying, given that it had such a dramatic impact on family life, on mental and physical health, on learning, can we pause? Can we learn from it? Can we talk about it? Can we build on these experiences to build a better educational and mental health future?

Sophia L. Ángeles is a tenure-track assistant professor of education in the College of Education at Penn State . She is the 2021 recipient of a Haynes Lindley Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship from the Haynes Foundation.

Lu (Priscilla) Liu is a lecturer in the Attallah College of Educational Studies at Chapman University in Irvine, California.

To read, “Reinventing Ourselves” and Reimagining Education: Everyday Learning and Life Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic,” visit the Harvard Educational Review website.