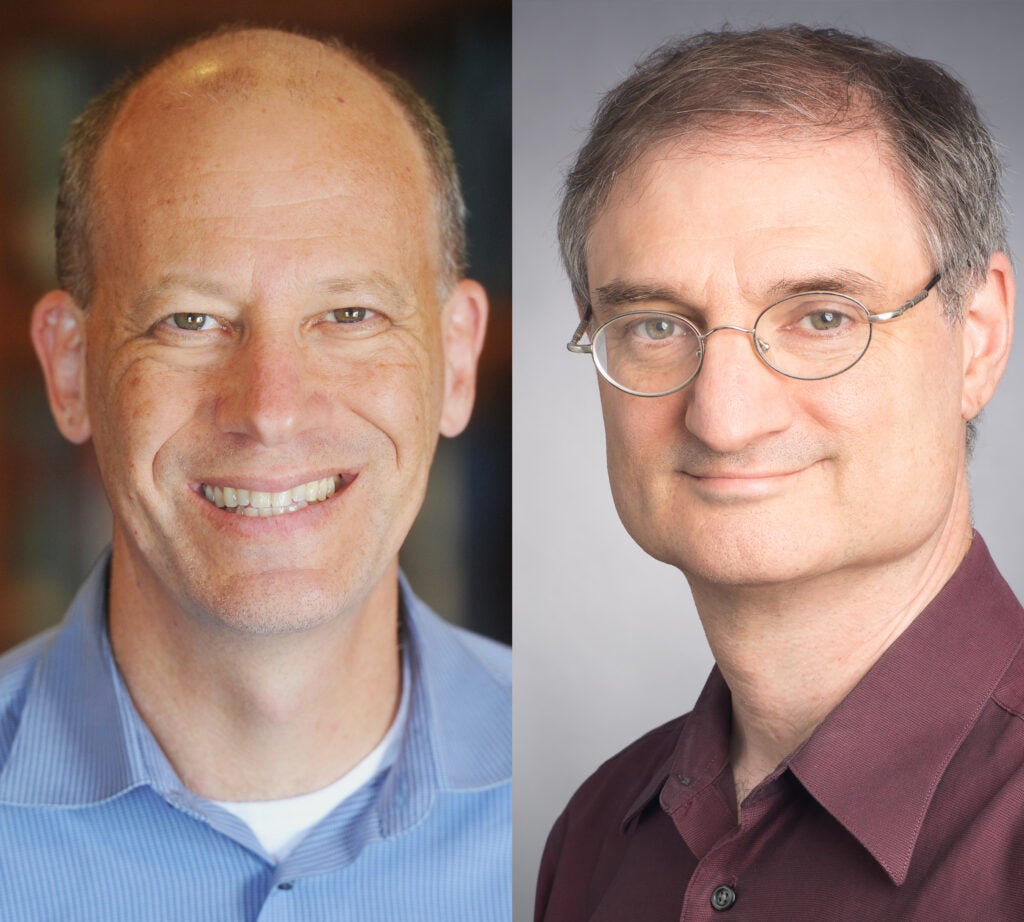

New paper by Joseph Kahne of UC Riverside and UCLA’s John Rogers and Alexander Kwako examines the new politics of education.

“If the ‘tempest of political strife‘ is let loose upon our common schools, they would be overwhelmed with sudden ruin.” – Horace Mann

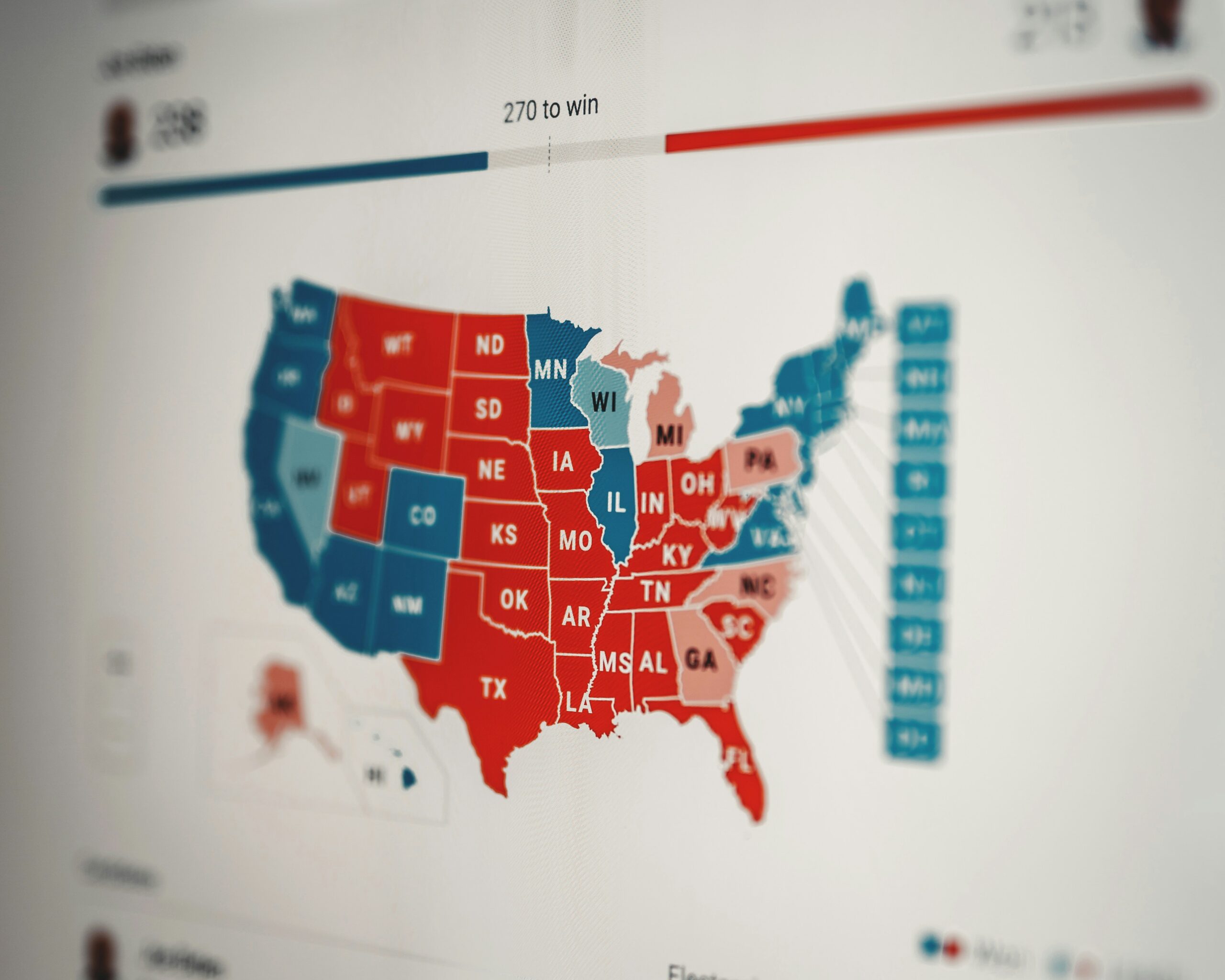

The politics of education in the United States have often been fierce. Yet throughout most of American history, these conflicts have reflected ethnicity, language, religion, or race and have not been organized around partisan identities.

That appears to be changing.

In a new research paper published in the AERA Open journal, “The New Politics of Education and the Pursuit of a Diverse Democracy,” Joseph Kahne of UC Riverside and John Rogers and Alexander Kwako of UCLA explore increasing partisanship in local education settings and the implications for public schools. As perspectives on education related to diversity increasingly align with political parties, education toward a diverse democracy has become a highly partisan issue. A central finding of the study is that parent and community-driven conflicts as well as actions to support education for a diverse democracy, are associated with a school’s partisan context. The paper underscores the increasingly partisan politics of education and how current partisan pressures threaten public schools’ efforts to educate toward a diverse democracy. The study aims to inform understanding of the new partisan politics of education, set forth priorities for future research, and, ultimately, suggest directions for strategic action on the part of educators, policymakers, and others.

“Public schools seem to be teetering dangerously close to the reality of Mann’s prediction,” says Rogers, a professor of education at UCLA and director of the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education and Access. “The increasingly partisan politics of education make it vital that we understand and assess how partisan pressures threaten public schools’ efforts to educate toward a diverse democracy and develop strategies to address the challenges.”

The research paper, one of the first large-scale studies of how a school’s partisan context may influence educational priorities, underscores increasing levels of partisanship and details how the level and context of partisanship are influencing conflict in schools and the response of educators in support of educating for a diverse democracy.

“Bringing young people together from different cultures and backgrounds to explore the full range of knowledge is essential to learning and to preparing students for full and fair participation in a diverse democracy,” says Kahne, a professor of education policy and politics and director of the Civic Engagement Research Group (CERG) at the University of California, Riverside. “Educational efforts to promote a diverse democracy are fundamentally important, and it is deeply troubling that such efforts appear threatened by the new partisan politics of education.”

The study drew on a unique national survey of 682 high school principals, conducted by Rogers and Kahne in the summer of 2022. Detailing the impact of increased partisanship, the study finds that high schools in purple contexts (those with more evenly mixed levels of Democrat and Republican support) are particularly likely to experience parent and community pushback related to education toward a diverse democracy and that schools in both purple and red communities are less likely to provide support for this priority.

The authors write that, as Mann predicted, growth in these partisan divisions has been associated with far greater political strife, constraining educators’ efforts. Across the nation, parents and community members, with support from conservative philanthropies, legal advocacy organizations, and grassroots networks, have used school board meetings as a stage for highly contentious and sometimes violent rhetoric that attacks both school board members and local educators. The study reports that conflict in schools initiated by parents and community members was common, especially in purple and more affluent communities. The levels of conflict and resistance from parents and community members, as reported by principals, were sizable.

Overall, almost eight in ten principals reported conflict from parents and community members tied to issues related to race and racism, teaching about controversial issues, or policies and practices related to LGBTQ+ youth. Worrisomely, almost a third (31%) of district leaders in a nationally representative survey reported that parents and community members made written or verbal threats against educators in their districts for teaching politically controversial topics during the 2021–2022 school year.

The report argues that the current contention in schools may be tied to the increasingly polarized nature of American politics, which has grown substantially over the last two decades. In particular, affective polarization, which measures the degree to which partisans dislike, fear, and distrust members of the opposing party, has grown precipitously.

Additionally, substantial evidence indicates that anti-democratic values and the politics of resentment are drivers of current political conflict and resistance to education toward a diverse democracy. This troubling trend, sometimes called democratic backsliding, erodes democratic commitments to equal participation, pluralism, and informed debate. The authors contend that it may unleash attacks on efforts of public schools to promote policies on diversity, equity, and inclusion; lessons that support students to judge the credibility of information; and curricula that expose students to the full history of the United States and encourage free and robust discussion of controversial issues.

The politics of resentment, including racial resentment and anger toward perceived elites, is also closely tied to current conflicts in schools and resistance to education toward a diverse democracy. Mobilizing feelings of resentment has become a central strategy in the new partisan politics of education. It is used by conservative media, think tanks, philanthropies, and politicians to build and deepen commitments to a partisan coalition as part of a broader political strategy. Since 2020, representatives of the Republican Party and allied activist groups have increasingly criticized priorities linked to education toward a diverse democracy, such as diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives and efforts to support LGBTQ+ students.

In this partisan context, such factors also influence whether or not a school provides supports for educating toward a diverse democracy. The study finds that although purple communities experienced the most parent and community conflict, high schools in both purple and red communities were less likely than those in blue communities to provide supports aimed at enabling education toward a diverse democracy. Principals in these schools were far less likely to report that they or their districts provided professional development and that they took action to promote education toward a diverse democracy than were principals of high schools in blue communities. In short, the more conservative a community, the less the support for education toward a diverse democracy.

The report also makes clear that the chilling of supports for diverse democracy can occur with or without partisan conflict. While political conflict was most pronounced in purple communities, lack of support for education toward a diverse democracy was more pronounced in red communities. The lack of community-driven conflict in red communities may well result from those communities having few advocates for education toward a diverse democracy.

Additionally, students are more likely to make hateful and demeaning remarks in schools with high percentages of white students. Specifically, in schools with higher percentages of white students, principals were more likely to report students making hostile and demeaning remarks toward African American youth, LGBTQ+ youth, and classmates holding opposing political viewpoints.

Schools in more affluent communities (those with a lower percentage of students receiving free and reduced price lunch) also were more likely than other schools to experience parent and community conflict.

Politics and demographics are not destiny. Democracy-minded leadership matters.

“While increasing partisanship is fueling conflict in local education settings, politics and demographics are not destiny, democracy-minded leadership matters,” says Kahne. “The research shows that both district and school leadership can make a meaningful difference.”

Schools with civically engaged leaders and schools in districts with leadership that emphasized democratic priorities were far more likely to promote education toward a diverse democracy. In some school districts in the survey, superintendents or other district leaders underscored the importance of democratic aims by speaking about civic and democratic priorities in meetings with principals or by asking principals for evidence related to their efforts to advance civic and democratic goals. Principals in those districts were much more likely to report that they made statements to their staff regarding the importance of diverse democracy and that their schools or districts provided professional development in support of that goal.

Additionally, principals who were themselves civically and politically engaged were far more likely to encourage education toward a diverse democracy than those who were not. This connection may indicate the value of hiring principals who are civically engaged and of supporting all principals to develop skills and understandings related to civic engagement in a diverse democracy.

“As our schools face partisan attacks, these findings seem to offer some hope,” says Rogers. “Even in the context of the new partisan politics of education, both school and district leaders have the power to make a difference. It is essential that education leaders feel empowered and encouraged to take action.”

“The New Politics of Education and the Pursuit of a Diverse Democracy,” is published in the AERA Open Journal.