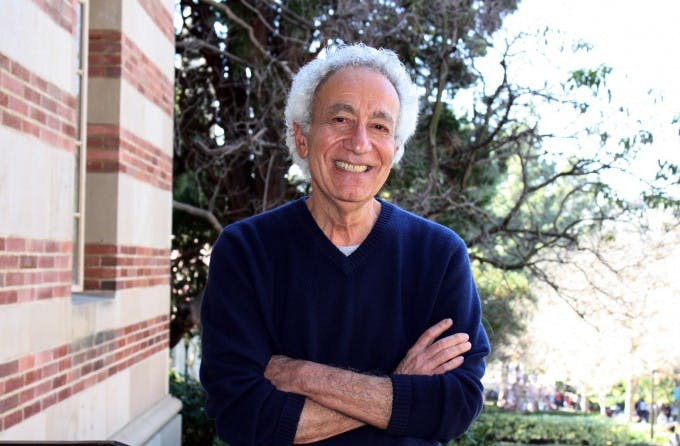

Mike Rose, research professor in the division of Social Research Methodology at UCLA’s Department of Education, has been honored for his career-long guidance of students with the Spencer Foundation Mentoring Award.

“We are all extremely proud of Professor Rose’s most recent recognition,” says Wasserman Dean Marcelo Suárez-Orozco. “Mike is a maître-penseur, a gifted writer, and generous colleague. As this important award from the Spencer Foundation highlights, he is an outstanding mentor. Congratulations, Mike!”

Professor Rose is a member of the National Academy of Education and the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Grawemeyer Award in Education. He has received awards from the Spencer Foundation, the National Council of Teachers of English, the Modern Language Association, and the American Educational Research Association.

Rose has appeared on more than 200 national and regional radio and television outlets, including Fresh Air, Bill Moyers’ World of Ideas, Studs Terkel, NPR Weekend Edition, and Tavis Smiley. He is a regular contributor to the Washington Post’s education blog, “The Answer Sheet” by Valerie Strauss. His previous books include “Possible Lives: The Promise of Public Education in America,” “The Mind at Work: Valuing the Intelligence of the American Worker,” and “Back to School: Why Everyone Deserves a Second Chance at Education.”

Professor Rose delivered a Presidential Session at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, speaking on “Writing Our Way into the Public Sphere.” He has been previously recognized by the Spencer Foundation with several grant projects, including “The Misjudgment of Literacy” as principal investigator in 1986; “The Study of the Learning and Cognition of Skilled Work” in 2000-2001; 1999, and 1997. He was named to the Spencer Mentor Network in 1998.

Rose shares his thoughts on being a mentor, those who have guided him throughout his own education and career, and the two-way rewards of the mentee-mentor relationship.

Ampersand: Who were your greatest mentors and what stood out about how they encouraged and shaped you?

Rose: I have been fortunate beyond belief in having many mentors, from my senior year in high school to well beyond the PhD. It would be impossible for me to talk about my development without this rich and extended web of support. I’ll select several to give you a sense of what I mean, but please understand that they collectively have made my life possible.

Jack McFarland, my high school senior English teacher. He was the person who transformed me from a mediocre, drifting student to a young person interested in books and ideas, and he was the first teacher to talk to me about going to college. It was in his class that I began to learn to think critically and carefully and to pay attention to my writing, to work at it, to want to get better at it.

Mr. McFarland helped get me into a small college as a probationary student, and after a bumpy freshman year, I had three English professors and a philosophy professor who continued what Jack McFarland set in motion. Each had a different interpersonal and pedagogical style, and a different way to approach books and ideas, and it was that variety that helped me grow.

You have to understand that this whole world was so new and strange to me. Neither of my parents, both Italian immigrants, had gone beyond elementary school, and though they loved me deeply and wanted the best for me, they weren’t in a position – either educationally or in terms of social class – to prepare me for or guide me through this strange new world of higher education.

I honestly don’t know if each of these professors thought consciously about working with first-generation students or how much they thought about social class. I was pretty clueless myself about all that. But each of them provided rigorous and compassionate tutelage, showing me how to read difficult books, how to write more precisely, how to think carefully and convincingly.

Fast forward through college, and then lots of teaching and tutoring jobs, to my PhD program here in the UCLA Department of Education many moons ago. My advisor was Richard Shavelson, who would go on to be a renowned cognitive educational psychologist and applied statistician. Let’s think of McFarland and Shavelson as educational bookends, for formal education, anyway, since, let’s face it, we’re always getting educated…and sometimes taken to school.

And Shavelson took me to school. He approached things in a way so different from the humanities orientation I had absorbed in Mr. McFarland’s English class and then in college. We were the Odd Couple, for sure, but, you know, I learned so much from him, learned another way to think, acquired an entirely new set of analytical tools. And the combining – I might even say, fusion – of these different ways to approach the world would prove invaluable to me as a teacher, writer, and researcher.

Mr. McFarland’s class was also the beginning—in school, anyway—of a political education that would slowly develop in and through the books and classes I mention above. But a really important political mentor for me was a peer (mentors don’t have to older or further up some institutional food chain): Lillian Roybal Rose (no relation).

In my mid-twenties I joined a wonderful War on Poverty program called Teacher Corps. Danny Solorzano was also in it a few years after me. Lillian was one of my teammates. She is the daughter of Congressman Ed Roybal, a major force in Mexican-American politics both locally and nationally. Lillian grew up in a household that ate, drank, and slept progressive politics, a household very different from mine. We became fast friends, and her friendship created for me a daily master class in political awareness, in yet another way to see the world and act on it.

&: From those experiences, what do you bring to your own role as a mentor?

Rose: When I think back over all the exceptional mentors I had, I can see what I drew from them that, over time – and I stress that “over time” point; our own development as teachers and mentors is gradual, experimental, integrative, and fraught with blunders – has contributed to my own mentoring:

Assume intelligence and give people challenging work.

Listen to what people tell you as they do that work. Really listen. What captivates them. Challenges them. Confuses them.

Expect growth to be difficult. It can be fulfilling, invigorating, confirming…but it will have its periods of difficulty.

How you respond to that difficulty is crucial. Try your best to understand it. Be compassionate about it. But also help people work through it.

&: What does being a mentor mean to you?

Rose: I get deep pleasure out of thinking hard with people about issues that matter to them. To do this effectively, I have to listen carefully, try to understand as best I can what their projects are and why they care about them—and what, if anything, is vexing them.

I often work with students whose fields I don’t know a lot about, so typically I can’t give quick and precise guidance: “do this;” “look at this study.” I’m not a very good mentor in that regard. But I can get them to articulate in as plain a language as possible their projects, the conceptual and methodological assumptions undergirding them, and why they are drawn to them, why they matter. Then I try to repeat back to them what I am hearing, which can be clarifying.

There’s something else that goes on in this process, and it is rare and valuable. Both of us have to slow down in several ways, no easy thing in the current pressure cooker of graduate study and especially of one’s early career. Physically taking the time (a telling phrase) to sit and think and talk, but also trying to execute a slow-motion on cognition: Why am I saying this? Why exactly am I using this framework or method? Why, really why, do I give a damn about this topic?

There are times, though, when I do get quite specific, very micro-level and hands-on in working with others—and that is with writing, thinking together on the page, so to speak. This kind of close work demands that I’ve been listening and have a sense of what people are trying to do with language. Then I might suggest to them a transitional move that gets them from point a to point b, or a syntactic structure that can logically connect the ideas they’re trying to connect, or phrasing that more precisely expresses the thought or feeling they’re trying to convey.

I think you have to model stuff like this, show people how to do it, share the writerly tricks of the trade you’ve learned over the years. As with assisting the mastery of any performative skill—surgery to dance—you have to show as well as tell.

&: What is the most critical thing that you want your students to walk away with from your mentorship of not only their academic work, but their career and lives?

Rose: Whew. This is a hard one, for there’s a lot to say. Will you let me pick two things I’d like people I work with to take from our time together?

The first is to be as conceptually and methodologically wide-ranging as you can be. I know the name of the game is to specialize, to master a theoretical approach to the world and a methodology harmonious to that theory. I understand. And, to be sure, you do want to develop expertise. But to the degree you can, spread your wings a little. Try out a few other conceptual lenses, learn at least a bit about other methodologies. The issues we study are so, so complex that we need more than one line of sight on them. And the more ways we have of seeing, the better mentors we’ll be for the range of students who will be seeking our help.

The second is to develop the art of listening. It’s stunning how seldom we really listen to each other. Think about it: How often in conversation do you get the sense that you are really being heard, that someone is actually responding to what you are saying, is trying to understand you? My point here ties into your third question: I think that good mentoring emerges from trying to understand people’s projects, why they matter to them, what they want to achieve with them, and what barriers they might be facing.

If I had to pick one thing that made a huge difference for me, I think it would be that each of the people in my life who helped me grow believed in me. That is such an extraordinary thing that one human being can do for another: to believe in and affirm another person’s ability.