While growing up in Iowa, John McNeil experienced some pretty harsh winters. However, at the age of eight, he learned…

While growing up in Iowa, John McNeil experienced some pretty harsh winters. However, at the age of eight, he learned that other children had it worse than he did.

“This was a lesson I learned in the 3grade,” he recalls. “It was cold as the dickens in Iowa, below zero. My mother had put a string on my mittens so I wouldn’t lose them. I hung them up in the cloakroom [at school], these brand-new mittens. And then one day, they weren’t there. I got angry because someone took my mittens, I made a big fuss for two or three days. Finally, the teacher called me over. ‘Do you want your mittens?’ she asked. ‘You bet I want my mittens.’

“So, she told me where to go and I went trudging through the snow. I came upon this little house that had a tar paper roof. This little lady came out with all these kids, and she held these mittens. I realized right away that that woman was in a desperate situation. I just felt ashamed of myself for making a big noise, not knowing what I was doing. This little boy in my room had taken them, of course. I never forgot that.”

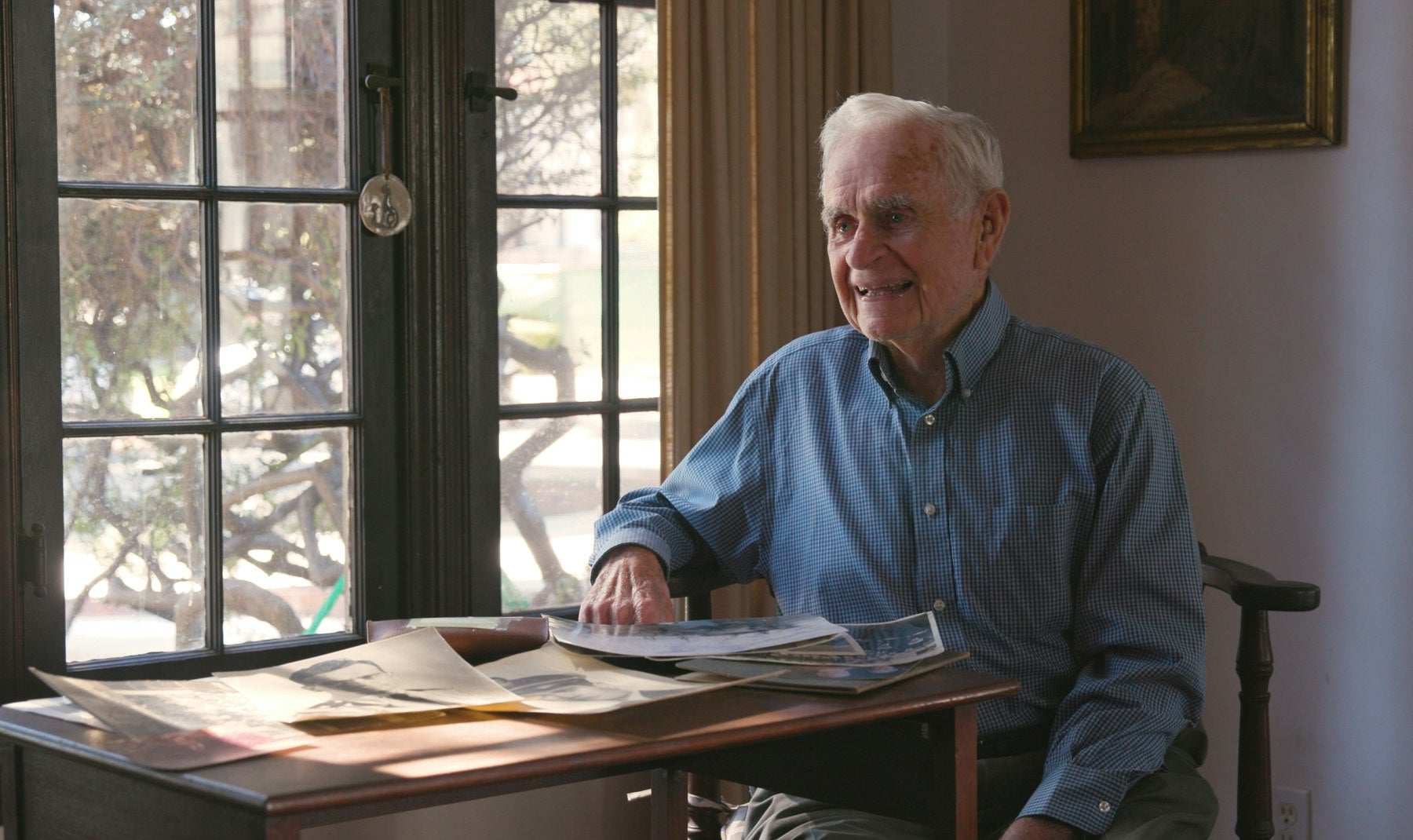

An awareness of those who need help has been a common thread throughout McNeil’s career. For the last three years, the UCLA emeritus professor of education, who turns 99 on October 29, co-taught a course with UCLA lecturer and former student Octavio Pescador (’93, B.A., Political Science; ’03, Ph.D., Education) on entrepreneurial philanthropy. UCLA undergrads worked on projects of their own invention that address issues including health, the environment, and reducing inequality.

Working in groups, the students tackled solutions to build morale through music in disaster-ridden Sri Lanka, preventing overpopulation and venereal disease in Africa with condom use, local programs for migrant children in Los Angeles, and preserving aboriginal languages in Japan. Students also learned how to write grant proposals and conversed via Skype with nonprofit leaders in developing nations like Guatemala and Honduras, to name a few.

“They were charged with actually making a difference,” Professor McNeil says. “Whatever their project was going to be it would contribute to having an impact. I’m just astounded by their imagination and ambition.”

Before arriving at UCLA in 1956 to lead the Teacher Education Program, McNeil, who had moved with his parents to San Diego prior to World War II, taught at a combination junior-senior high school that he helped to establish in 1947, and wrote instructional materials for local school districts. His students were from families who had migrated west during the Dust Bowl era of the 1930s, as his family had moved from Iowa to find better opportunities during the Great Depression. McNeil often focused on the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a document adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948 that sought to prevent the atrocities that took place during the Second World War from happening again. The document also represented a guarantee to basic human rights including the right to work in just favorable conditions; the right to education and the benefits of cultural freedom and scientific progress; and the right to the highest attainable standards of physical and mental well-being.

“They were wonderful kids, I enjoyed the teaching experience tremendously,” recalls McNeil. “I told them about propaganda and how doctors were advertising Camels cigarettes on TV to get the kids to smoke. Or, you’d see a magazine ad with, “Dr. So-and-So smokes Lucky Strikes.” I had them write propaganda themselves so they would know what it was.

“Then one night I got a phone call and it was the principal of the school. He said, ‘I want to fire you, we can’t keep you in the school any longer.’ This was the time [of] the Red Scare. Everybody was afraid of the Communists and they were taking our library books and burning them. I asked, ‘What’s the charge?’ and he said, ‘They think you’re a Communist.’”

McNeil later found out that the father of one of his students – a man who worked for the public school district – had made the charge against him. He was surprised so he met with the man and after McNeil explained his beliefs about how students learn the man dropped his opposition. McNeil later became curriculum director for San Diego public schools before leaving for Columbia University to earn his doctorate. However, this was not to be his last brush with revolutionary and subversive ideas.

“While I was at Columbia, UCLA needed someone to take over the Teacher Education Program, so they invited me to come here,” recalls McNeil. “The salary was terrible, if I told you, you wouldn’t believe it. But I said I would rather be here because I would have more influence than if I stayed in San Diego. It was a tremendous opportunity, a tremendous place to live and spend one’s life.”

Under the guidance of Dean Howard E. Wilson, McNeil was to realize the goals of civic engagement, social justice, and inquiry that remain the standard of UCLA’s GSE&IS today. Having served as an officer in the Navy during WWII, Professor McNeil was able to give back to his fellow veterans by leading a program that provided teacher training for retired military personnel. He also set the UCLA standard for preparing educators to serve all students in Los Angeles: Instead of giving his student teachers assignments in affluent West Los Angeles neighborhoods near campus as was the norm, he had his teacher candidates – who were predominantly female – spend at least one of their apprenticeships in an inner-city school.

“I put that as a rule, to get involved with the area that was [perceived as] more threatening at that time to our teachers,” says McNeil. “I’m trying to give a picture of the emotions of that time, and the racism was terrible. I got phone calls from students’ boyfriends and fathers – ‘You can’t send my daughter … you can’t send my girl to Watts.’ But they went, they were willing to do it and it opened their eyes to a forgotten part of the city.”

Dean Wilson also wanted his faculty to become more engaged in international research. Professor McNeil was sent to Mexico to write curriculum and conduct professional development workshops for teachers, and create a national reading program for Mexican schools. In addition, McNeil and a colleague, who had created the first computer instruction in schools, were invited to Mexico in 1960 by the wife of President Diaz Ordaz to demonstrate it there, underwritten by Howard Hughes.

McNeil went on to conduct similar projects and research in Latin America, Jamaica, and the Caribbean. He says that he learned to appreciate the value of parental and local educational interventions.

“I learned in Jamaica that when the parents and students participate in the development of their own activities like learning math, for example, kids learn from their parents and those [lessons] endure,” says McNeil. “But when outsiders come and say, ‘Take this program and use it,’ the books are put aside and students’ learning suffers.

“It’s the same thing as when [ebola] came to Africa. People were dying, and outside medical experts came and said to burn the bodies – it didn’t match their culture. But when Africans built their own defenses against the illness rather than adopting outsiders’ treatments, they finally stopped it.”

Back at UCLA, Professor McNeil taught through the turbulent Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam War protest years.

“It was intense,” he recalls. “Police helicopters were hovering all over the campus. The students tore off the railings from around Moore Hall, it was so destructive. One quarter, I was asked to enroll former prisoners and revolutionaries into my class. It was a curriculum course, and there were about 30 of them, really kind of off the streets. But I liked them, they spoke honestly, and we all learned.”

McNeil muses on the innovative ways that UCLA’s Graduate School of Education & Information Studies continues to influence the most pressing questions that challenge education in Los Angeles, California, the nation, and the world.

“The influence here is tremendous,” he says. “You’ve got [Wasserman Dean] Marcelo Suárez-Orozco and Carola Suárez-Orozco, who work so much with migrants; Carlos (Alberto Torres, UNESCO Chair in Global Learning and Global Citizenship Education), who is with UNESCO. They’re worldwide UCLA – they’re making a tremendous difference now. [Migration is] the big issue today, all over the world … and here it’s UCLA that’s on top of that.”

The big question, according to McNeil who has been in the middle of the debate for decades, is “What is education?” He answers his own question saying, “We don’t know yet. That is our topic right now in the United States, right in [Moore Hall]. What do we mean by education? What should it be? Preparing for just a job, preparing for intellectual enlightenment? What is the purpose of education? What does it mean for your children? That’s where I am at the moment.”

When asked what he is most proud of after 60-plus years on the UCLA campus, his naval service at the Battle of Normandy, and a global career in education, Professor McNeil demurs.

“It’s more like… things I’m most grateful for,” he says. “It would take all afternoon to summarize it. It’s been the most wonderful experience. Even things that were disheartening – looking back on them they were really something.

“The people – that’s one thing I am grateful for at UCLA. So many of the people I’ve known here are the greatest people. It’s the humanity, it’s the people, That’s one reason I’m not too concerned about time. They contributed so much to my life, every one of them. So many are not here anymore, they’re only in my memories, but I’m grateful for having known them.

“It’s been a wonderful voyage. It’s people, it’s opportunities, it’s imagination. It’s getting into heaven ahead of time.”

McNeil earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English from San Diego State University, as well as his lifetime teaching credential. He achieved his doctorate in curriculum and instruction at Columbia University. He is the author of “Contemporary Curriculum” (8th Edition. Hoboken: Wiley, 2014); “Curriculum: The Teacher’s Initiative (Pearson, 3Edition, 2002) and “International Development: Challenge and Controversy” (Sentia Publishing, 2018).

For a video of Professor John McNeil by UCLA Newsroom, visit UCLA on YouTube. For birthday greetings from his colleagues and friends, visit Twitter.

Photo by Sebastian Hernandez, UCLA Newsroom

More birthday greetings from Professor McNeil’s friends and colleagues:

John – I am happy to see that frequent badminton playing leads to amazing longevity and vitality. Congratulations!

Bengt Muthen, Professor Emeritus, Social Research Methodology, UCLA Department of Education

At UCLA, in the department of Education, we have been honored to have John McNeil as a colleague. I say this from the perspective of my role as a colleague, former chair of the department and short period as Interim Dean. Although, our areas of academic specialization were different, I gained so much from my discussions with him. These discussions of course, occurred when he came home from settling important educational problems around the globe. I am privileged to be able to send him Birthday wishes and of course, a Birthday kiss.

Norma D. Feshbach Ph.D, ABPP

Professor Emerita, Chair, and Interim Dean, UCLA Graduate School of Education & Information Studies

“A treasure, a giant, a godsend…” There are no superlatives that do justice to John McNeil’s character and talents. I am witness to his leadership in teacher education, literacy research and development, curriculum studies, and bilingualism. He is one of the world’s greats and I am honored to be his friend and colleague.

Happy Birthday, Profesor!

Concepcion M. Valadez, Research Professor, UCLA Department of Education

Hi John – Happy Birthday! Even after being your student, your colleague, and your friend for so long, it still seems astounding that you have reached this important milestone. I will take this moment to thank you for the model you were for all of us students: open, enthusiastic, accepting, hard-working and innovative. I still remember how you pushed me to Conejo Valley (at age 23) to report on my linguistics curriculum project and get a job offer. My memories of you include your ability to exhaust all badminton players in by running them back and forth the court and your willingness to take and then love a yellow MGB.

Eva Baker, Distinguished Research Professor, UCLA Department of Education, and founding director, CRESST

Dear John – It’s hard to believe that we have known each other for 50 years! You actually brought me into the Graduate School of Education in 1968 and convinced me to decline Anderson School’s invitation to join them. I have always thought the world of you both as a scholar and as a human being. In addition to your own impressive productivity, you have an uncanny ability to make other people feel good about themselves and to inspire them to pursue their own work at elevated levels. I have always enjoyed our wide-ranging discussions — pedagogy, social issues, entrepreneurship, commercial real estate … you name it. I think pehaps few among your academic colleagues know what an astute businessman you are in addition to all your academic accomplishments. You have always been there for me, and I want you to know that I will always be there for you. Happy happy birthday, my dear colleague.

Marilyn Kourilsky, Professor Emerita, UCLA Department of Education