UCLA’s retiring Breslauer Professor of Bibliographical Studies serves on the Council of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences; chairs the Advisory Committee for the organization’s Humanities, Arts, and Cultures program.

UCLA Distinguished Professor of Information Studies Johanna Drucker has been elected for membership in the American Philosophical Society, as part of this year’s class representing The Arts, Professions, and Leaders in Public and Private Affairs. Founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin, the organization is the oldest learned society in the United States.

Recently, Professor Drucker was also appointed to the Council of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, which provides oversight of the scholarly and policy research activities of the Academy and its publications; reviews and recommends for their approval all academic studies and commissions undertaken in the name of the Academy; provides direction regarding the Academy’s publications, including the Academy’s quarterly journal, Dædalus.

The American Academy of Arts & Sciences, founded in 1780, is both an honorary society that recognizes and celebrates the excellence of its members and an independent research center convening leaders from across disciplines, professions, and perspectives to address significant challenges. Drucker, a member of the AAAS since 2014, has also been named the inaugural chair of an advisory committee for the organization’s program in Humanities, Arts, and Cultures.

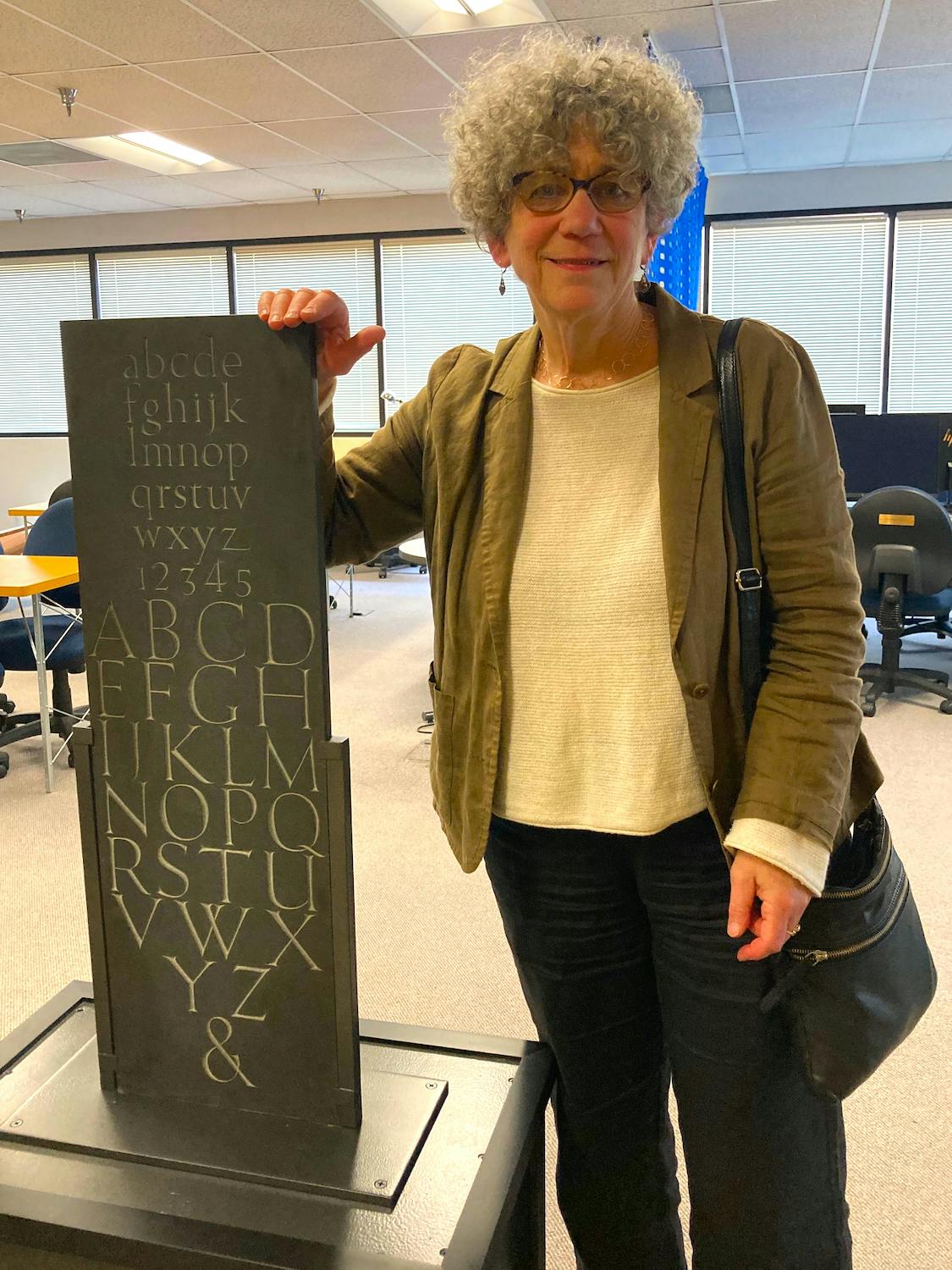

This spring, Professor Drucker, who is internationally known for her work in artists’ books, the history of graphic design, typography, experimental poetry, fine art, and digital humanities, is retiring from UCLA and leaves a unique parting gift to the UCLA Department of Information Studies, reflecting her love of the printed word, the reinstallation of a stone slate depicting the letters, “ABC” on side, and the entire alphabet on the reverse side.

The slate, which had been brought to UCLA in 1969 by David Palmer, a counselor of UCLA Psychological & Counseling Services. Palmer, who had a great interest in fine letters, discovered the alphabet slate while touring Fedden’s studio in the Cotswolds. Although Palmer couldn’t afford to buy the slate, Fedden insisted he take it home to Los Angeles, in hopes of finding a buyer for it. Ad Brugger, who was the executive secretary of ASUCLA at that time, and Andrew Horn, former assistant dean, and vice chairman of what was then the Department of the UCLA School of Library Service, shared Palmer’s appreciation for the slate, and it was obtained by the University. For a time, it was displayed in the student bookstore and later, near the School of Library Service, which was housed in Powell Library.

Fast forward to 2020, when UCLA was on lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Russell Richards, husband of Tabitha Fedden, Bryant’s youngest daughter, reached out to Professor Drucker, in the hopes that she could let him know the current home of the slate on campus. Drucker was able to locate the slate, which had eventually been placed unnoticed in the IS Lab in the SEIS Building. She had a sturdy plinth constructed as a base for the Fedden slate, and recently presented it to the UCLA Department of Information Studies.

Johanna Drucker, UCLA Distinguished Professor of Information Studies, with a slate depicting the alphabet, created by British craftsman Bryan Fedden. The slate, which arrived at the University in 1969, has been placed various locations, including Powell Library. Drucker recently had a sturdy base constructed for the slate and presented it to the UCLA Department of Information Studies. Photo courtesy of Johanna Drucker

Professor Drucker joined the faculty of the UCLA Department of Information Studies in 2008 as the inaugural Martin and Bernard Breslauer Professor of Bibliographical Studies. Among her recent accolades, she was honored with the 2021 Steven Heller Award for Cultural Commentary from the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA); the 2019 Alexandra Garrett Award for Service from Beyond Baroque Literary Center in Los Angeles; an honorary Ph.D in fine arts from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2016; and the Walter Ong Award for Scholarship, Media Ecology Association in 2015. Drucker was named the inaugural Distinguished Beinecke Fellow in the Humanities in 2018 by Yale University.

Professor Drucker’s most recent book, “Inventing the Alphabet: The Origins of Letters From Antiquity to the Present,” published by the University of Chicago Press, has been lauded by Science Magazine as just, “… not another history – it is a historiography, addressing the intellectual history of this crucial topic for the first time.” In the book, Drucker aims to dispel the misconceptions surrounding the existence of more than one alphabet – the myriad of letter forms throughout the world are actually considered as script – as well as the links between the original alphabet that was created around 1700 BCE and the alphanumeric notation that provides the infrastructure for the internet.

Drucker’s other notable books include “Downdrift: An Eco-fiction” (Three Rooms Press, 2018); “Visualization: Modelling Interpretation” (MIT Press, 2020); “Iliazd: Metabiography of a Modernist” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020), and “The Digital Humanities Coursebook” (Routledge, 2020). “Off-World Fairy Tales,” a collaboration with Susan Bee, was published in Fall 2020 (Litmus Press). Drucker’s work has been translated into Korean, Catalan, Chinese, Spanish, French, Hungarian, Danish, and Portuguese.

Professor Drucker achieved her Ph.D. in ecriture at the University of California, Berkeley, where she also received her master’s degree in visual studies. She has her bachelor of fine arts degree from the California College of Arts and Crafts.

What do you look forward most to doing with the American Philosophical Society?

It will be interesting to see. It was founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1743 for the purpose of promoting useful knowledge. The people who are elected [with me this year] come from every field, from math, physics, international relations, art, and archaeology. It’s meant to foster [an] exchange of knowledge across disciplines and among scholars and researchers.

I’m going to get to know the society and the nice thing is it’s in Philadelphia, which is my hometown. It’s in those buildings I always knew as a kid; it’s very venerable in that in that way.

What will be your goals as chair of the Advisory Committee for the Humanities, Arts and Culture for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences?

My role as chair of the Advisory Committee for the Humanities, Arts and Culture [is] first of all, to help constitute the committee. I’m sitting at a table with people who have major roles in advising the Museum of Modern Art, working with the Mellon Foundation, engaged in theater, the arts, and humanities nationally–so it’s a super brain trust. These are people who are really experienced and well-positioned in our cultural, philanthropic, and educational institutions. The role I have there is to engage them in conversation to help develop projects for the Academy and from the Academy, so it’s pretty exciting.

I’m trying to encourage this group to think a lot more in terms of public humanities and exchange, and not so much just outreach, but also intake. If you want people to feel like they are stakeholders in anything, you have to engage them – you can’t just go and take something to them. You have to want what they have to contribute.

Both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society are elite institutions, but [they are] very aware of the need to reconstitute their membership to diversify, not just in terms of the demographics of membership but in terms of projects and outlook… what constitutes authoritative research, and how do we understand knowledge in the 21st Century and effective modes of communication, of knowledge and distribution and production.

I’m really interested in how effective communication is designed. You can put it in blocks of plain grey text, which is what a lot of these academic publications look like, and guess what – it’s not working. I’m trying to get them to think in terms of forms of communication that reach a broader and younger audience. One of my suggestions for the Academy is that we should have a young ambassadors group, that we need to bring in high school students, college students, young people who are not necessarily in academic work but interested in community engagement, and talk with them about the future of knowledge.

By the time people get elected to the Academy, they are usually fairly advanced in their careers. The average age of people entering the Academy is 55 to 65. They’re accomplished, but they’re mid to late career, so that skews in a certain way. I’m hoping to enliven things a bit, kind of shake it up a little.

Given your history at UCLA of imparting a love of typography and print to your students, the reinistallation of the Bryan Fedden slate is such a fitting and generous parting gift. How do you hope future students and viewers of the slate will be inspired by it?

There’s a lovely corner where we have children’s books, our kind of reading area. It will be a nice piece to have visible. The slate was not my gift, just the refurbishing and mounting of it onto a pedestal so it can be appreciated as a work of the stone carver’s art. But also, these letters, so familiar to us in their Roman form, have a long history. The alphabet was invented in the Ancient Near East by Semitic speakers who were part of Afro-Asiatic culture. It spread globally and now undergirds communication (in its variant forms such as Arabic, Cyrillic, Tamil and many other scripts) throughout the world. I hope the slate will inspire our students and others to understand this long history.

My love of the alphabet was deepened by my work as a letterpress printer, but also as a scholar. While the alphabet has had a major impact on Western culture, its origin predates its adoption by Greek speakers by a thousand years.

If I could inspire any future pursuits at UCLA, they would be to respect the cultural otherness of the past and engage with the intellectual history of the human record. The Breslauer Chair was endowed by the descendants of German-Jewish book dealers and bibliophiles who respected long traditions of learning. I was honored to be the first scholar to occupy the position.