Upcoming publication by Peter Lang pushes out of the academic box with creative “ecowriting.”

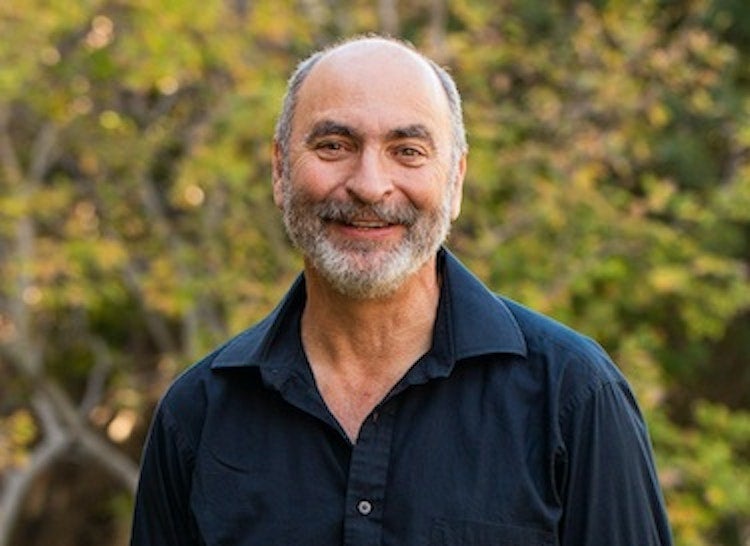

Jeff Share, a lecturer with the UCLA Teacher Education Program and Undergraduate Education Program, has been teaching a class on environmental justice for the last two years to undergraduates in the new Education and Social Transformation major. He was so delighted with the work his students turned in for an assignment on “ecowriting” – namely, creative, non-academic writing about environmental justice, climate change, and related topics – that he thought the results would make a great book. Share edited the end product, “For the Love of Nature: Ecowriting the World,” to be released by Peter Lang in early 2023.

Share, a scholar of critical media literacy, is the co-author of “The Critical Media Literacy Guide: Engaging Media and Transforming Education,” with UCLA Distinguished Research Professor Douglas Kellner.

A former photojournalist and classroom teacher, Share has taught in bilingual classrooms at Leo Politi Elementary School in L.A.’s Pico-Union community and served as Regional Coordinator for Training at the Center for Media Literacy where he wrote curricula and led professional development. Share continues to provide professional development in critical media literacy for LAUSD teachers as well as for educators throughout the United States and internationally. In 2015, Share published a second edition of his 2009 book, “Media Literacy is Elementary: Teaching Youth to Critically Read and Create Media.”

In October, Share chaired a keynote session on “Critical Media Literacy & Environmental Justice,” during the International Symposium on Democracy, Global Citizenship and Transformative Education, presented by the UNESCO Chair of Democracy, Global Citizenship and Transformational Education. His co-presenters were Theresa Redmond, professor of curriculum and instruction at Appalachian State University, and Antonio López, chair and associate professor of communications and media studies at John Cabot University in Rome. Share, Redmond, and López contributed a chapter on “The Global Perspective on Ecomedia Literacy, Ecojustice, and Media Education in a Post-Pandemic World,” in “The Routledge Handbook of Media Education Futures Post-Pandemic.”

What is ecowriting and how did it inspire “For the Love of Nature”?

Jeff Share: A couple of years ago, our Department let me design a class on environmental justice. I used the framework from critical media literacy to focus specifically on the environment, and how media and the messages we get about our relationship to the natural world are constructed and disseminated, as well as how various organizations use media to create strategic narratives about environmental justice and climate change. I also discuss how we can use media to challenge these types of messages and feel a sense of empowerment, in the midst of such overwhelming dangers that we’re seeing with the climate crisis.

Each time I teach this class, I focus more on the power of creating writing and media about our relationships to the environment. The students have been responding really well to this and some of the material they created is very impressive. I was blown away by what I was seeing them do.

My focus on ecowriting began after I read a great article by ecolinguist Gavin Lamb about ecowriting – writing about the natural world – and I used that as the inspiration for my students. They all read his article, and then had to create their own type of ecowriting. It was such a positive experience, and the students talked about how meaningful it was for them. They created poetry. They wrote letters, stories, fiction and non-fiction. One person wrote a short screenplay. It was powerful.

After the class I decided I would like to publish my students’ work and started checking around with different people I know around the world who are doing work in the same area. I asked them if I were to put together a book, could they send me an essay that would go along with this idea about the importance of ecowriting, and I received wonderful responses.

Antonio López in Rome, who is a pioneer in ecomedia literacy, sent me a chapter about creating environmental video essays. A colleague in Australia, who does powerful work with storytelling about our relationships with nature, sent me a fabulous chapter. I’ve been collecting their essays, and my students’ writing. I took it to a publisher, and the publisher loved the idea, and said, “You know, it’d be really great if we also had lesson plans.” So, I asked my former TA Andrea Gambino if she would be interested in writing lesson plans. She loved the idea, and with a former student of hers, wrote a series of excellent lesson plans.

It all came together beautifully and now we are creating a book of essays about different types of ecowriting by academics from around the world, examples of ecowriting by students who have gone through the class, and a whole collection of resources and lesson plans for teaching ecowriting. We’re also looking at the possibility of doing a collaborative publishing with the National Council of Teachers of English and Peter Lang. I’m in conversations right now with NCTE editors about whether we could co-publish this like we did with the last book that I co-wrote with Richard Beach and Allen Webb on teaching climate change to adolescents. We co-published that book with Routledge and NCTE.It gets better distribution when it has more people involved in this way.

This new book is very much a UCLA product, inspired by our own students, undergrads and grad students, and by what I’ve been learning from working with the students, teaching the class.

What do you feel are the most significant impacts of the pandemic on the environment and how can they be addressed?

The pandemic has done numerous things. I think one of the big things it’s done is showing us the possibilities of change, because a lot of people were very quick to say, this is not possible, that will never happen. And what the pandemic demonstrated is, yes, it can. We can shut down the entire society in a day, if we decide there is a serious crisis. This is something that Naomi Klein has been writing about for years before the pandemic. She would refer back to World War I and World War II, about how people made changes when there was a crisis.

What we need to do now is change the narrative and help people understand that the issue today is not climate change – the issue today is climate crisis. The more we can change the language behind this, the more likely we can start to shift people’s mindsets to recognize the severity of our current time.

With your career in photojournalism to the present, what are the changes you’ve seen in public perception, in regard to the environment, across generations and among all walks of life?

Anecdotally, from what I’ve seen and been hearing from my students and my son, is that the young people today are far more aware and concerned about this than old fogies like me. I think that’s a really important piece to recognize: that the youth are more serious, more understanding, and more active about this problem than anyone else. So many of the activists are young who are pushing different issues in terms of the environmental crisis around the world, from Greta Thunberg to the youth who filed the lawsuit against the U.S. government over the climate crisis, to activists in Africa, Latin America, all around the world – some of the strongest activists are our kids, our youth. That’s an important lesson for us to recognize. We need to be partnering with the youth, and we need to stop this kind of expert adult talking down to them and start working in collaboration with them.

The other group who I’ve been seeing and learning a lot from is the Indigenous folks in many parts of the world, who have for a long time been on the front lines of environmental issues and have been living sustainably with the land for thousands of years. We need to be looking towards them for leadership. We need to be supporting them, working in solidarity with them as allies, with the Indigenous communities who have been doing this work much longer than us, who know what they’re doing, and who have been struggling against the destructive forces of colonialism and capitalism for so long. We have a lot we can learn from them about disrupting our colonial ideologies and practices, repairing our disconnections from the natural world, and recognizing our interdependence with nature.

What do your students’ writings reveal to you about their hopes and fears around nature and the environment?

That they’re very concerned. They’re passionate about this and for many of them the climate crisis is the number one issue. Even in classes where I’m not teaching environmental justice, that always comes to the forefront. Students bring in questions about, “what does this mean for the environment?” I am more and more trying to bring environmental justice into every class I teach, because I think it’s a theme that can’t just be looked at as a separate subject. In reality, it’s connected to everything.

In a few years, everyone is going to be feeling the impact that many of the southern hemisphere island nations and poor areas are already feeling today. The climate crisis is not just a thing of the future. One of the big issues that I explore with my students is the inequality of the environmental crisis, it’s affecting everybody, but not equally. Some people are highly impacted right now, and other people won’t be impacted for a while. It is essential that we understand that inequality is a social and environmental justice issue, it is all connected.

It is also important to consider the myth of universal responsibility, as if we are all equally responsible for this crisis. While it is good for all of us to be conscientious about our own carbon footprint and our individual impact on the environment, it is much more important to hold our government and corporations responsible for all they have done and continue to do or not do that is causing this environmental emergency. Our own military burns more CO2 than most countries around the world. Fossil fuel companies continue to make astronomical profits while they have known for decades the scientific evidence about their culpability for global warming. So, there are certain entities that that have tremendous responsibility and enormous power, that if they decided to stop burning fossil fuels or change their extractive policies we could change the future.

One of the things we’re seeing more often is people who were denying climate change are now starting to say, well, yeah, okay, it is real, but it’s only because of overpopulation. This is a way of shifting the blame from us in the northern hemisphere, who are using far more fossil fuels and emitting much more greenhouse gases than any of the people in the southern hemisphere. Even though they are having more children, they are not contributing more to global warming. And so, this attempt at blaming overpopulation is really a racist trope that’s just trying to deflect responsibility from the ones who are benefiting the most while they have been contributing the greatest amount of CO2 into the environment.

How has social media changed these perceptions, whether they’re among the young or people, our age, or even older people?

We are seeing a lot of the youth using social media for activism. And I think that’s one of the shining lights here: since it is the youth who are pushing forward so much of the critical work in terms of environmental justice, they’re using the tools they know. Many young people know how to use social media much better than us older folks. I go to my son all the time for help, to teach me how to do things with my phone and access all the different apps. I think that’s also a tremendous help in terms of organizing movements towards changing society in a way where we can be more sustainable and more just.

Another place we are starting to see change is in the environmental movement. In the United States it has been isolated, very White and middle class. In fact, there were times when the environmental movement would go up against the working class, against unions. And now we’re seeing a big shift in terms of bringing social justice and intersectionality into our understandings of environmental justice, and more people of color are at the forefront of the environmental movement.

There’s a great article that my students read every year, written by Hop Hopkins in the Sierra Club, and it’s titled, “Racism is Killing the Planet.” He writes powerfully about White supremacy and sacrifice zones, how there are certain places we know we can dump our trash or put our polluting industry, and that’s always in areas with large concentrations of people of color and poverty. He argues well that environmental justice is intimately connected to social justice.

.