Jean Ryoo, director of research for the Computer Science Equity Project (CSEP) at UCLA Center X, has been honored with the Jan Hawkins Award for Early Career Contributions to Humanistic Research and Scholarship in Learning Technologies by the American Educational Research Association (AERA). Ryoo, an alumna of UCLA’s School of Education and Information Studies (’13, Ph.D., Urban Schooling) will be recognized in a virtual awards ceremony during the Division C Business Meeting on April 9 and will deliver the Jan Hawkins Lecture at AERA in 2022. UCLA Distinguished Professor of Education Sandra Graham will preside over the ceremony.

This year at AERA, Ryoo will chair a panel discussion on, “Who Has a ‘Seat at the Table’?: Equity in Decision Making About Computer Science Education” that features Black educator voices from her work with schools in Mississippi. She will also present her co-written paper, “Student Agency in Computer Science: Teaching and Learning Socially Responsible Computing in High School Classrooms,” with Jane Margolis, senior researcher for the UCLA Computer Science Equity Project, and Alicia Morris, LAUSD. Both events will take place virtually on Monday, April 12.

Ryoo is currently leading a longitudinal study titled, “REAL-CS Student Voices,” working with Margolis, that highlights the experiences of high school students who have had little to no prior experience with computer science and who come from backgrounds that are historically underrepresented in computer science.

Prior to arriving at UCLA, Ryoo worked with the Tinkering Studio of the San Francisco Exploratorium, to direct research-practice partnerships focused on equity issues in afterschool STEM making programs, including the California Tinkering Afterschool Network. Ryoo’s varied experiences as a museum docent, afterschool educator, and classroom teacher inform her research with the tools to identify and address the inequities that youth and teachers face in different educational contexts.

Ryoo and Margolis have a forthcoming book slated for release in 2022 with MIT Press, a graphic novel for teens that explores issues of inequality related to race, class, and gender in education and computer science. Ryoo achieved her M.Ed.T at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa and her B.A. in Visual and Environmental Studiesfrom Harvard University.

Ampersand met with Ryoo and discussed the progress of national efforts to engage students of color and girls in computer science, the added difficulty that under-resourced schools have in the pandemic teaching computer science – sometimes without a computer – and what keeps her motivated to opening doors for students that have until now remained firmly closed.

Ampersand: How has equity in computer science education progressed?

Jean Ryoo: Ever since Jane Margolis published, “Stuck in the Shallow End,” [in 2008], there have been these large movements to create new courses, like Exploring Computer Science, that are culturally responsive, inquiry-based, and offer rigorous learning opportunities for youth who have been kept out of computing education. And in 2016, President Obama brought forth the CSforAll movement, and so there’s there’s been this great push forward across the nation. We’ve been trying to create these opportunities for youth, especially young women, students of color, youth [from] low-income communities who are highly underrepresented in the field of computing, for meaningful computer science education.

But that being said, there are still very few students learning computer science. In the state of California—that serves majority students of color—even though we’re home to Silicon Valley, only 3 percent of high school students take computer science. It’s clear that when we see that the computing fields are primarily made up of white men and certain Asian men … there’s been this tracking of youth.

I give all that background because in all of these efforts to push for computer science education for the past decade-and-a half, we really aren’t hearing from students. And yet, students are the ones that know best about what works and doesn’t work in education.

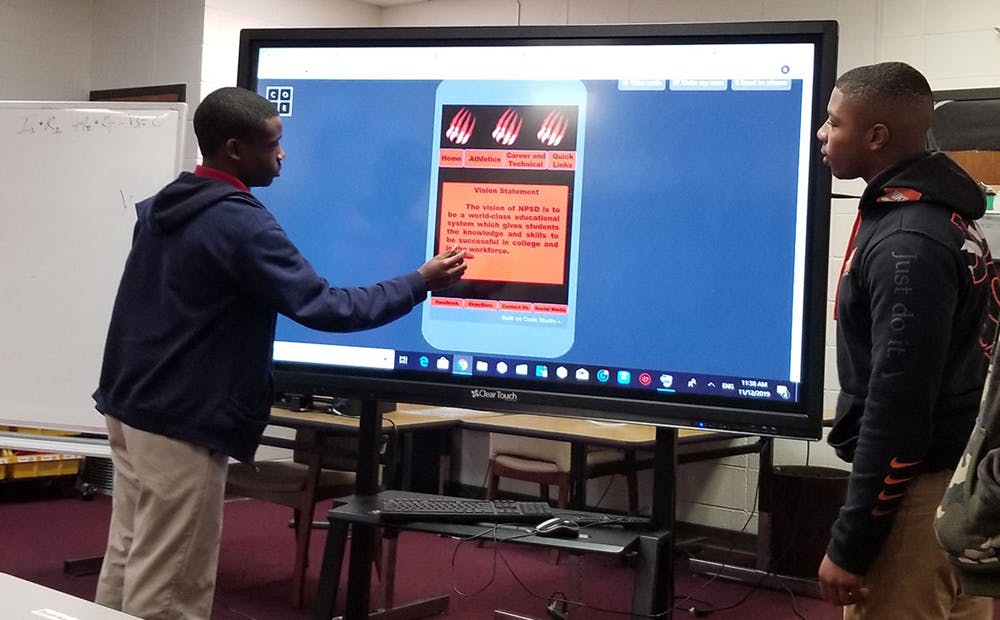

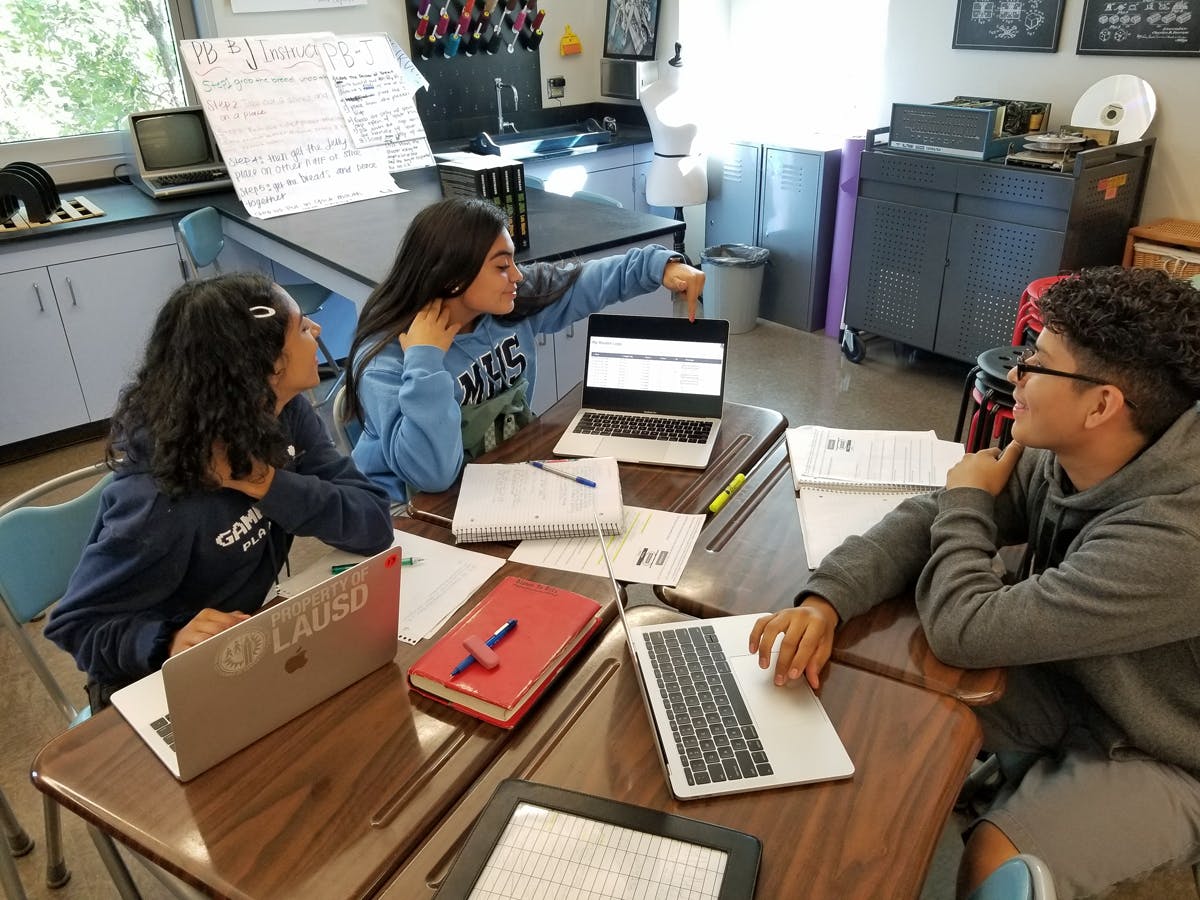

That’s what got Jane and I super excited when we started this work together [to find] how we can work in partnership with educators and students to understand students’ experiences in computer science classrooms, especially students who had little to no prior experience in computing, and who are young women and students of color in LAUSD and in rural Mississippi. We wish to amplify the voices of the Latinx, low-income urban youth and Black rural low-income youth in the South who we work with. Recognizing that computer science is a form of power in today’s world that touches everything we do, think, and feel, our work has really been about supporting student agency so that youth can think and speak out critically about the world around them.

&: How has the pandemic affected your study?

Ryoo: A lot has been cut short because of COVID-19 last year in the middle of our time in Mississippi just as we were getting to know the students and the teachers. We’ve been interviewing students on Zoom to learn about their experiences with computer science, but we’re not getting to know them as well since we’re not with them in their classrooms. But we hope that as the pandemic wanes, we will get to see how the students’ CS experiences in Mississippi continue with them or not as they move through high school into their first years of post- high school life, whether that’s university, community college, or no college at all. We hope to connect with the students in-person and over time as we have been able to do in L.A.

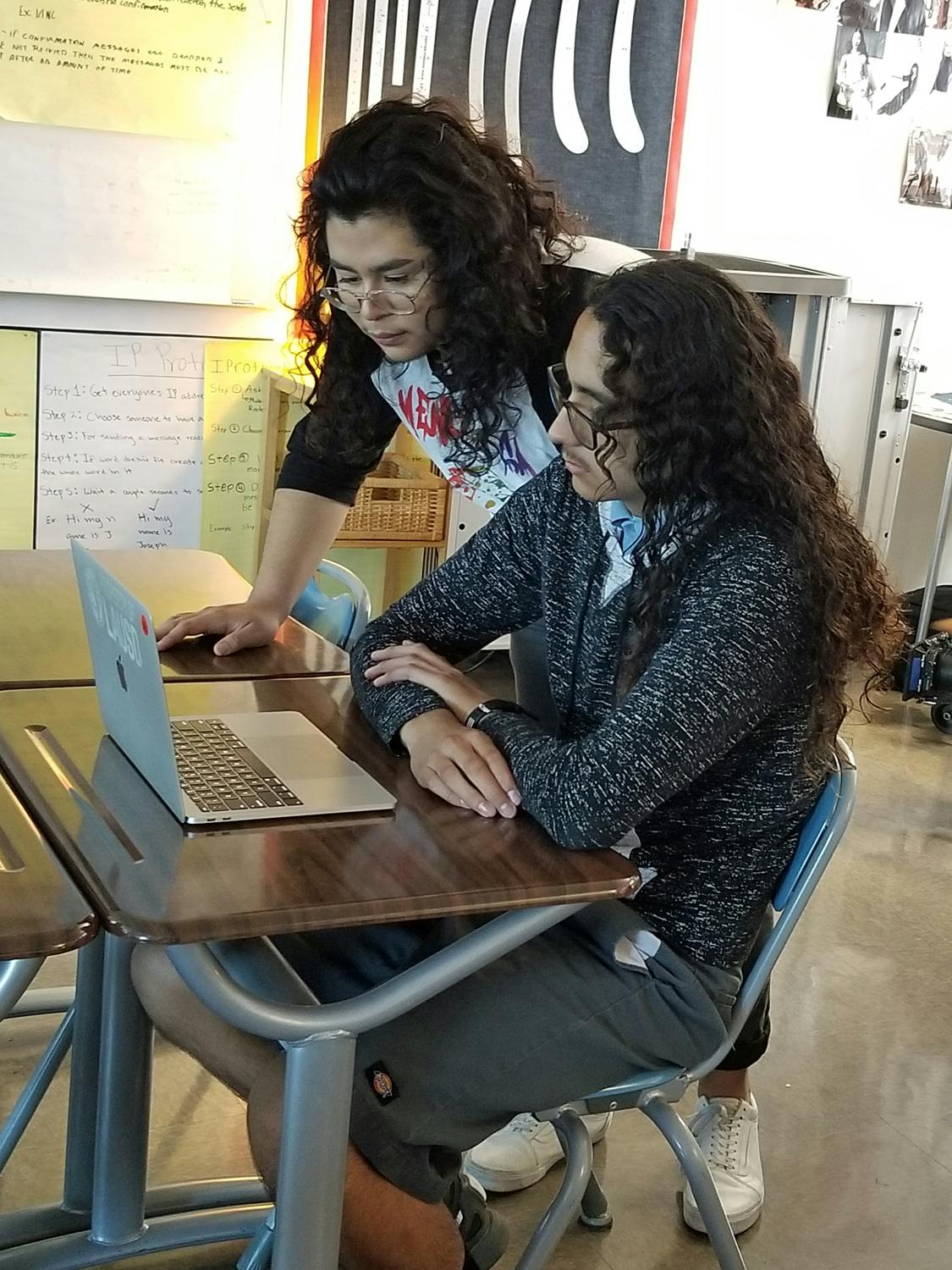

We’ve had to put … the ethnographic piece of being in the classrooms on hold, which is sad because that’s really the place where we would be close with the teachers, get to know the students, get to know the students’ lives. I’m approaching this work with a socio-cultural theory lens, so, in other words, thinking about how learning doesn’t happen [for] a student alone with their books or computer – that learning is a social practice that takes place in a very specific historical context of a place and a time and the politics and culture of the time and the people and its history.

It’s really important for to me to be able to understand student learning and how that relates to their sense of identity and engagement in computing. That is why we were doing this very close observation of classrooms as well as interviewing the students and conducting these surveys from their pre- and post-experiences with computer science.

In one of our schools in Mississippi, the students haven’t met, even online. They’ve just been given packets to do at home, without even a computer or Wi-Fi because the district had a lot of trouble getting devices and Wi-Fi to students. They’re just expecting kids to do everything on paper without experiencing learning together and with teachers. That obviously limits what students can do and learn with computing.

At the other school in Mississippi, the district thought they had everything in place for the start of school in fall of 2020, but then so many students did not actually have devices or Wi-Fi at home. It took a while for the school district to accumulate the devices and then get them distributed, and so they did not have online meetings as a requirement for passing classes, and again, it was all asynchronous work.

COVID-19 has been really a terrible thing for our schools and our children and our teachers – the exhaustion and frustration that our partner teachers experienced throughout this pandemic. So much of what is surfacing in this research is the value of the learning experiences, the relationships, the community building, which is not something easily attainable through asynchronous activities or even online learning contexts.

This research is really focused on student voice and understanding also the relationship between computer science, education, and students’ sense of self and agency – do they feel like they can do something in the world with what they learn? Our theory is that if they don’t have a sense of identity or agency with a subject, why would they ever want to learn it?

Exploring this topic has been really exciting, especially in our findings that illustrate the importance of making computer science learning relevant to students’ personal interests, their passions, and also having a positive impact on the world. We already know this from the work of great scholars such as Gloria Ladson-Billings, Luis Moll, Na’ilah Nasir, and many others about the importance of supporting practice-linked identities, making connections to students’ lived realities and funds of knowledge, etc.

The tendency is for people to think that teenagers are self-absorbed and don’t think about anything besides their Instagram postings, but it’s really not true. In our research, the students have been voicing that they have all of these issues that they care about, whether it’s Black Lives Matter, women’s rights, issues around LGBTQ, the environment – very real problems that our world faces that the students want to address. When computer science is taught to them in ways that show them how computing can be used to address real world issues and problems, student engagement increases and learning deepens.

Computer science is impacting all of these issues very deeply, as we see with racist algorithms and AI – like the incredible research that Safiya Noble (UCLA associate professor of information studies) has been doing, for example, and that Cathy O’Neil, Ruha Benjamin, Timnit Gebru, Joy Buolamwini and Meredith Broussard and many others have been doing. Interestingly, they’re all women – and many are women of color – who have done this research around these deep problems in computer science and these deep ethical issues that are impacting our society today. And yet, that’s not often talked about in schools, especially not in computer science classrooms. It’s been really inspiring to learn from the youth about how much they see these connections and want their computer science education to make those connections for them so that they can make a difference.

I am also supporting a major project led by Julie Flapan and Roxana Hadad, which is a research-practice partnership across the state of California, working with 14 different school districts and local education agencies. These efforts overlap with CSforCA.

We’ve developed what we call the Equity Guide, which is essentially a handbook of different issues to take into consideration if you are an administrator, school leader, or district leader interested in bringing computer science into your school, so that you can avoid problems that create more inequalities as well as introduce computing in equity-centered ways. That is coupled with an administrator workshop that our group also developed [in] collaboration with our school district partners across the state, that includes people whose districts have really been at the forefront of bringing computer science into schools, as well as districts [that] are just now beginning to bring computer science into their schools.

&: What does being honored by AERA in the name and legacy of Jan Hawkins mean to you?

Ryoo: Jan Hawkins was such an amazing woman and scholar and researcher, and she emphasized the importance of working in partnership with educators, with community, and why there needs to be more of that. Perhaps that might also have been why they were interested in my work because that’s something I really think is important.

I don’t do this alone. When I see this award, I really see it as a as a reflection of the larger community that I have the privilege of being part of in this work, with the teachers and the students and the school district leaders and other instructors and other researchers.

&: What propels your career in educational research, particularly a field that is as vital as equity in computer science education?

Ryoo: First of all, computer science education is really a window – this is how Jane would say it – a window into seeing how segregation and inequality work in our schools. If you want to understand how tracking works, if you want to understand how racism and sexism work to deny youth access to an education they deserve, just look at computer science education.

I’m angered and frustrated by the ways youth have been denied the education they deserve. How can it be that in this day and age, things could still be so backward when it comes to our young women, our youth of color, our low-income students or immigrant students, English learners, students with disabilities – they have been pushed out and denied access to computing knowledge and skill base that impacts absolutely everything in our everyday lives.

Our youth [should have] the opportunity to have the critical thinking skills and the abilities to understand how computer science works – regardless of whether or not they want to become computer scientists. What I care about is that they can be critical thinkers who understand how computer science functions because without that knowledge, our communities will continue to be manipulated and used, our data taken, our privacy lost. And no one will even notice it’s happening and how and why.

The second thing that propels me in this work is that I feel computer science education offers an opportunity to completely reimagine and rethink what teaching and learning look like in our schools. In this newer field of study, we have an opportunity to innovate and introduce learning experiences that are more humanizing and [committed to] a liberatory practice.

If you look at the history of technology and its implementation in schools, from radios to TVs to VHS to DVD … there’s this vicious cycle. Everybody gets excited, they spend a ton of money on it, but then teachers are not given professional development to understand how to use it. And then, all of a sudden, yet another new technology comes out and all the other stuff becomes outdated. Money was lost, but schools feel pressured to spend more money on the newer technology, and the cycle begins again. I think it’s really important not to get stuck in that cycle, [focusing] simply on the technological tools themselves. We must focus on the greater purpose of what we want to achieve with those tools toward critical thinking, creativity, and engaging in inquiry-based processes that support skill development.

Computer science… touts itself as a field that thinks outside the box, that is creative and imaginative, that can solve our world problems. If that’s really true, then we have this opportunity to create innovative curricula and support educators in new ways of teaching that are culturally sustaining.

The technology alone is not what matters. It’s how we use it and understand the impacts of technology that matter: does technology support social good or cause harm? We need to be thinking about issues of civic engagement in connection with computer science. At this point, there is cause to worry about how technological innovation is creating harm for communities of color through algorithmic bias, racist facial recognition systems, etc.

What really fuels me in this work has been the relationships and the community building. Every time I interview a student, every time I get to visit them in the classroom, every time I get to work with my partner teachers in LA Unified or in Mississippi, I feel so honored. They carry so much wisdom and knowledge and experience and that’s what I get really excited about, is seeing the world through their words and their vision and passions. I feel deeply responsible to amplify what they’ve shared, to do right by them… so that they can be part of that process of amplifying their stories, as co-authors or as participants in a conference presentation or a book or story or article.

There are many students that I communicate with regularly, as well as teachers with whom I am building lifelong friendships. And when you have that community that you build together through a project like this… again, I feel, very honored and lucky to have that opportunity. That’s what keeps me going – the people that I’ve met and the things we’ve been able to learn together.

Photo by Raymond Gaston