When Ellen Pearlstein traveled to Japan this summer to visit cultural heritage sites in both Honshu and Hokkaido, she had the unique experience of learning to make washi paper, a handcrafted fibrous paper that is used traditionally for decorative purposes, such as origami, woodblock printing, and calligraphy.

“I teach students about the qualities of paper that impact its preservation and I use paper in physical conservation of collections,” says Pearlstein, a professor in the UCLA Department of Information Studies. “I primarily teach the conservation and deterioration of items made from organic materials – wood, leather, shell, bone, ivory, and paper. We research documents, perform treatments, and also design housings for those types of materials.”

For Pearlstein, washi has great significance as a material used to repair and conserve fragile artifacts and documents. She visited the village of Echizen-shi in Fukui Prefecture to learn how to make this handmade material from Naho Murata, an expert craftsperson who has made washi there for more than 20 years. Echizen-shi has very little tourism and Professor Pearlstein’s visit, her research on washi, and her papermaking lesson with Naho-san were covered in local newspapers.

“Echizen-shi is noted for their paper, a result of the fertile growing conditions for papermaking plants and the quality of the water from natural springs,” says Pearlstein. “There are multiple old master paper makers, and Echizen-shi papers are sold at Hiromi Paper in Santa Monica.

“[Washi] is used as a repair material or a lightweight backing [because] it’s very strong but also very porous,” she says. It’s used to repair not only sheets of paper but also three-dimensional objects like baskets and wooden sculpture.”

Pearlstein says that the process of making washi, which is composed of pulp made from various types of inner bark, is very demanding, both physically and mentally.

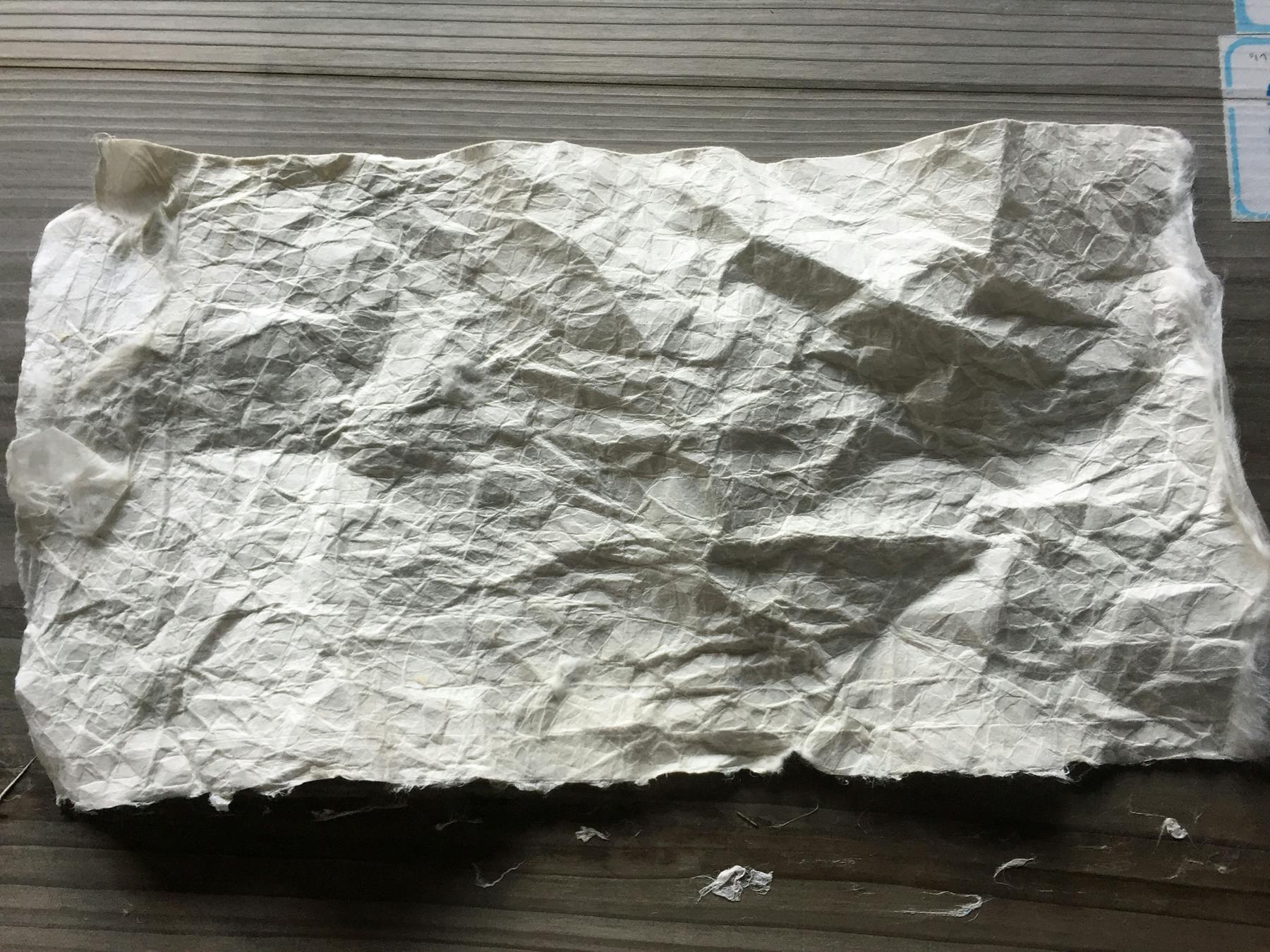

“It was remarkable to me how difficult it is to actually produce a high-quality sheet of paper,” she notes. “It takes years and years to learn how to do this, so I made very simple paper. They would not let me use the highest quality plant pulp because I was just learning. I used a coarser pulp with a lot of woody inclusions in it. The paper I made is quite handsome looking but it’s not suitable for conservation because it’s not as highly refined as the paper used for that purpose.

“Papermaking by hand is a combination of using your mind and body – you have to be very particular in your motions in order to produce an even and strong sheet of paper,” says Pearlstein.

Professor Pearlstein is a scholar in the UCLA/Getty Program in the Conservation of Archaeological and Ethnographic Materials. She is the editor of the book, “The Conservation of Featherwork from Central and South America.” She is currently working on the book, “Developments in the Conservation and Care of Indigenous Collections,” to be published by the Getty Conservation Institute as part of its Readings in Conservation series.

Courtesy of Ellen Pearlstein