TEP senior lecturer Jeff Share co-edits and alumnae Andrea Gambino and Amber Medina pen chapters to support K-12 teachers in empowering students.

“Empowering Youth to Confront the Climate Crisis in English Language Arts,” a new book co-edited by Jeff Share and published by Teachers College Press in collaboration with the National Writing Project (NWP), draws upon educators’ first-hand experiences and critical media literacy to examine ways that teachers can help students find ways to address the climate crisis in K-12 classrooms. Share, who serves as senior lecturer in the UCLA Teacher Education Program (TEP) and undergraduate major, is joined by UCLA alumnae Andrea Gambino (’23, Ph.D., Education) and Amber Medina (’21, M.Ed., Elementary Education and Teaching), who contributed chapters to the book based on their research and expertise. Share, Gambino, and Medina recently took part in a podcast for the National Writing Project, with Richard Beach and Allen Webb, co-editors of “Empowering Youth to Confront the Climate Crisis in English Language Arts.”

Gambino is the founder of Inquire 2 Transform, a community-engaged consulting firm specializing in critical media literacy and project-based learning. She provides research and instructional consulting to K-12 and higher education institutions, including the Los Angeles Unified School District and Stanford University. Also a contributor to Share’s 2024 book, “For the Love of Nature: Ecowriting the World,” Gambino wrote the chapter, “Challenging Climate Disinformation Through Critical Media Literacy and Ecowriting” for the new book.

Medina, a former elementary classroom teacher, wrote the chapter on, “Engaging Elementary Students in Inner-City L.A.” for this volume. She has created content for the nonprofit SubjectToClimate, worked as an Environmental Science and Garden Teacher at an environmental charter school in Los Angeles, and is currently a Program Coordinator, working on a civics education project for the Los Angeles Superior Court.

Share’s research and practice focus on the teaching of critical media literacy in K-12 education and environmental justice. He presents at international conferences, provides professional development at schools, and has trained teachers in critical media literacy in India, Mexico, China, Iraq, Germany, Poland, Hungary, and for the Fulbright Foundation in Argentina. At UCLA, Share created a required course in critical media literacy for TEP teacher candidates, as well as courses in critical media literacy and environmental justice for undergrads in the SEIS Education and Social Transformation major.

Share’s books include “Media Literacy is Elementary: Teaching Youth to Critically Read and Create Media,” “Teaching Climate Change to Adolescents: Reading, Writing, and Making a Difference” (with Beach and Webb); and “The Critical Media Literacy Guide: Engaging Media and Transforming Education” (with UCLA Distinguished Research Professor of Education Douglas Kellner).

Beach, Share, and Webb served as guest co-editors for a special issue of English Journal, published by the National Council of Teachers of English. To read, visit this link.

Share, Medina, and Gambino discuss “Empowering Youth to Confront the Climate Crisis in English Language Arts” and its potential to be a gamechanger for teachers in preparing students to examine the most pressing issues through a social justice and critical media literacy lens.

What inspired “Empowering Youth to Confront the Climate Crisis in English Language Arts”?

Jeff Share: Richard Beach, Allen Webb, and I co-authored the previous book, “Teaching Climate Change to Adolescents: Reading, Writing, and Making a Difference.” We wrote this book in 2017, making the argument for why English language arts teachers need to be engaging with climate and environmental issues. At the annual conferences of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) there have been roundtable sessions for teachers to present about how they are incorporating climate change into English Language Arts.

After about five years of these roundtable sessions, we decided that there’s a lot of valuable material that should be shared. So we chose about 20 amazing presentations and requested short chapters from each of the presenters about their work, and that’s how we curated this powerful collection of essays.

What in your research and practical experience informed your chapters in the book?

Amber Medina: I was an elementary school teacher for three years, and I taught middle school for one year. My chapter was about engaging young elementary students in inner city Los Angeles and trying to reach teachers and give them support on how they can integrate environmental education and environmental justice seamlessly with an interdisciplinary approach.

Teachers are tasked with so much. In the multi-subject sector, I found myself overwhelmed with the regular K-12 standards in the curriculum, and on top of that, trying to find a way to integrate it without a lot of training and resources. Environmental education can be blended into standards that already exist. I talk a bit about how I learned this during my experience working with the nonprofit, Subject to Climate. I started with them while I was attending UCLA and still working on my credential, and I was able to adopt their inquiry process of developing curriculum – a method that flows from inquiry to investigate to inspire.

Sparking that curiosity with young students is essential and so is giving them the tools and agency to learn things on their own while supporting them in that journey. It ends with empowerment, always adding that element of being agents of change; moving away from ‘It’s this eight-year-old’s responsibility to save the world,’ and more about learning the history of injustices and the activism embedded in it, and how they can be part of that change for a better future.

Andrea Gambino: My chapter highlights the important work of teachers, with elementary and high school students. We know that climate messaging is complex. Climate disinformation can quickly go viral on social media, and it often includes advertising campaigns from companies that promote false messaging about environmental sustainability and ethics through greenwashing.

In my chapter, I go into studies about how teachers work with students to take a close look at the fossil fuel and fast-fashion industries and how they’re able to use curated text sets – media from printed word to video, to social media post, to documentary. They develop their learning around a documentary called “IMPACT x Nightline: Unboxing Shein,” that traces a story of a fashion designer from southern California and how her designs are stolen online and reproduced underneath Shein’s label in a fast-fashion way that harms migrant workers, as well as perpetuates the climate crisis through overconsumption models and toxic dumping. Students learn about the “Six Sins of Greenwashing” to think about rhetoric, how arguments are used, and tools of persuasion that trick audiences. They use the critical media literacy framework to analyze ads and how this false promotion of ecolabels, all the way down to “earth-friendly colors,” actually misleads consumers to believe, “I’m doing something good for the environment.”

I also look at work done with elementary learners and how they use think-aloud strategies, such as: See, Think, Wonder and climate-justice children’s literature, so that they can explore larger issues where there is always hope included. A core element of this book that shines across the authors – which you can always anticipate in a Jeff Share publication – is that there’s going to be strategy, but there’s also going to be hope. We know that to sustain the climate justice movement and the work we do as educators, we have to have hope as the baseline.

Share: In my chapter. I talk about the role of language and the way, grammatically in English, we turn nature into objects. We use the pronoun it instead of he, she, or they and when we refer to nature we refer to it in third-person voice, thereby objectifying the natural world. When we do that, it becomes easier to exploit and harm plants, animals, land, water, and air, as opposed to a more Indigenous perspective, where nature is looked at as something sacred and alive.

One activity I describe in my chapter, involves encouraging students to tell a story from the perspective of a tree, or a mountain, or nature – shifting our lens in order to recognize the value and importance of the natural world. I connect this with the international movement for the rights of nature. Even in the U.S., legal systems are starting to question this notion of who has legal rights to be able to sue, to be protected. There’s a growing movement that argues nature should have these rights, especially considering that we already give legal standing to corporations, some of which are causing tremendous damage to the very world that we depend on.

What are some of the challenges of teaching young students in an urban setting about this and how these issues affect them?

Medina: The biggest challenge has been shifting the focus from individual responsibility to a broader, systems-level understanding—helping students recognize the structural roots of environmental issues and the importance of holding corporations and institutions accountable. One of the lessons I talk about in the chapter is green spaces. I taught this unit with my students in South Central Los Angeles, so we would look at air pollution in those areas in comparison to Pasadena and Beverly Hills and then overlay that with green spaces maps to see that correlation and talk about some of those consequences.

It becomes a lens of looking at government entities and turning to them to be our advocates as well. It sounds complicated when I say, “I’m talking to elementary students about how we can write letters to our local government bodies and state administrators, showing them that young activists are doing this type of work.” But I always tell people, even outside of environmental education, not to underestimate an elementary school student. They have such a fresh take on everything, especially in this changing world.

Students are now growing up with AI and ChatGPT and so many digital resources are accessible to them. They are entering with a very different tool set. They don’t need a million dollars for an advertisement. They can jump on TikTok or Instagram and share their ideas for free. It’s tapping into all the resources a child brings to the table and not selling them short. It’s also taking on how we challenge the way our government functions, who we’re holding accountable, and how we advocate for ourselves, giving students the tools to have their voices heard.

How did the Los Angeles wildfires provide a moment in which to underscore the importance of environmental education?

Gambino: The first week the wildfires began, I met with a group of climate educators from NCTE who were asking, “How are you maneuvering this? How are you getting information?” I shared how crucial the Watch Duty app and citizen journalism were, being able to maneuver different platforms, but pausing to critically think and question what I was seeing. I found myself using the critical media literacy framework questions in real time, not only questioning misinformation but also exploring environmental racism and the unequal impact of the wildfires on low-income Angelenos.

I was extremely grateful to be able to rely on some of my academic training and specifically my work with Jeff, Amber, and colleagues, to be able to maneuver that because as we know, the emotions were heavy. A lot of this was reactive in the moment, and that’s a painful space to be in, especially as an educator. It was a reminder how crucial climate literacy is – and understanding language like burn zone, burn scar, knowing how to read the air quality index, thinking about toxins – and how many more lessons we need, to be proactive rather than reactive.

No one is left untouched by the climate crisis. My home state, North Carolina, was also affected by Hurricane Helene. I was thinking about the growing number of climate catastrophes across the United States and around the world, and at the same time, how communities can come together under dire circumstances. It’s an important time to integrate social justice and environmental justice education.

Do you think that environmental justice will be a graduation requirement in K-12, in the way that critical media literacy has become?

Share: I think it absolutely will. As the climate crisis gets worse and worse, people start to realize the importance of it. Just like the public discourse from the Los Angeles wildfires, people are starting to talk about the damage of global warming on our homes and our communities.

More and more, people are recognizing that these are global issues, and as the climate gets hotter, we experience more extreme weather events, whether they’re storms, droughts, floods, or fires. There is so much evidence in all parts about the climate crisis, from the disappearing glaciers to the expanding deserts. People aren’t going to be able to keep denying global warming.

At some point, educators will realize this is the most important crisis of our time and we need to prepare students how to adapt to it and also how to mitigate the problems. Schools need to address the realities and help students learn how to change the ways we’re living, to reduce the over-consumption, and especially how to change the systems and structures that are the root causes of our problems. We need to be empowering students to take actions demanding corporations and governments stop exploiting the environment and people, stop extracting and burning the fossil fuels, and start creating healthier, sustainable, and more socially just alternatives.

Jeff Share will present a workshop on “Exploring Critical Media Literacy and Making Memes,” on Sunday, June 8, in the Glorya Kaufman Community Center at the Wende Museum in Culver City.

The free event is open to ages 14+. For more information and to register to attend, visit Eventbrite.

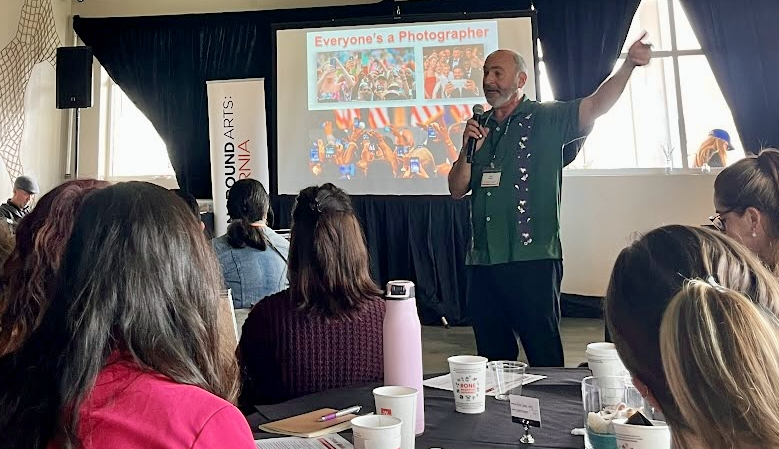

Above: Jeff Share speaks with teachers at an event with Turnaround Arts California, a nonprofit that supports the capacity of teachers and principals to lead for change through the arts.

Courtesy of Jeff Share