Commentary: Knowledge That Matters

As Californians anxiously await the results of the recall election, residents of Los Angeles likely are unaware that the LAUSD Board of Education will make a pivotal decision on Tuesday with implications for the future of how our schools are funded and governed. The Board will vote on whether to request that the U.S. Department of Education grant flexibility in how the district uses federal education funds. This seemingly innocuous request will unleash what is being called, “Student Centered Funding” (or “SCF”). SCF would reallocate district funds (in line with an unspecified set of student characteristics) and greatly shift budgetary decision-making to the local school level.

I applaud the idea of directing resources to schools with the greatest needs and involving those most impacted in making decisions about how to use these funds. Indeed, I previously have testified on both of these issues before the Board, encouraging it, for example, to adopt the “Equity is Justice” framework energetically supported by organized youth in 2014. But LAUSD’s new move toward SCF seems to be less about supporting high-needs schools or local engagement and more about prompting movement of students from one school to another. Under SCF, additional dollars follow particular students, rather than ensuring that all schools provide all students with the conditions they need and deserve. I am worried that the Board is rushing headlong to adopt a plan that will advance neither equity nor democracy, and may well undermine other valued district purposes.

Before taking a vote that will lead the district inexorably toward SCF, LAUSD Board members should discuss and provide answers to four simple questions.

First, what are the goals of this finance reform and why is SCF a good way to achieve these ends? District officials have suggested that SCF will create “equity, transparency, flexibility, and sustainability,” but they have said little about what these terms will mean in LA schools and communities. In its public documents and presentations, the district has pointed to several other districts that it claims have adopted SCF–for example, Baltimore, Chicago, and San Francisco. Yet there is no single finance model that these districts have embraced, nor any clear outcomes that map onto LAUSD’s goals. Reviewing the evidence a couple years ago, Rutgers University Professor Bruce Baker argued that many districts who adopted student centered funding became less transparent and no more equitable.

Second, how will SCF empower local school communities to make informed budgetary decisions? In theory, SCF shifts power from the district to the school, allowing educators and the school community to “purchase” personnel or programs that address their unique needs. If LAUSD favors local decision-making, it needs to build infrastructure and capacity. For principals to play a meaningful role in school-based budgeting, they will need much more administrative support and professional development in how to work collaboratively on the budget with teachers, community members, and students. And, the teachers, community members, and students will need training as well. We know from many other examples nationally, that this shift will take time and require substantial resources.

Third, how will SCF impact LAUSD’s stated goal of building community schools and strengthening communities? By attaching dollars to individual students, SCF encourages schools to compete to attract students that bring the most funding. This approach likely will increase student mobility and undermine the stability of neighborhood schools. If the district was serious about strengthening communities, it might provide additional dollars to schools based on the number of enrolled students who live within walking distance of the school (a policy that would enhance community stability and would be good for the environment.)

Fourth, why pursue SCF now? LAUSD appears poised to transform how it funds and governs schools amidst a pandemic and during a period of interim leadership. In the coming months, the district will be holding a national search for a new superintendent. That search presents an opportunity for the board to engage stakeholders and the broader community in public discussions about how to achieve educational equity and support democratic participation. The Board should take full advantage of that opportunity and pursue these goals with a superintendent who fully embraces that vision.

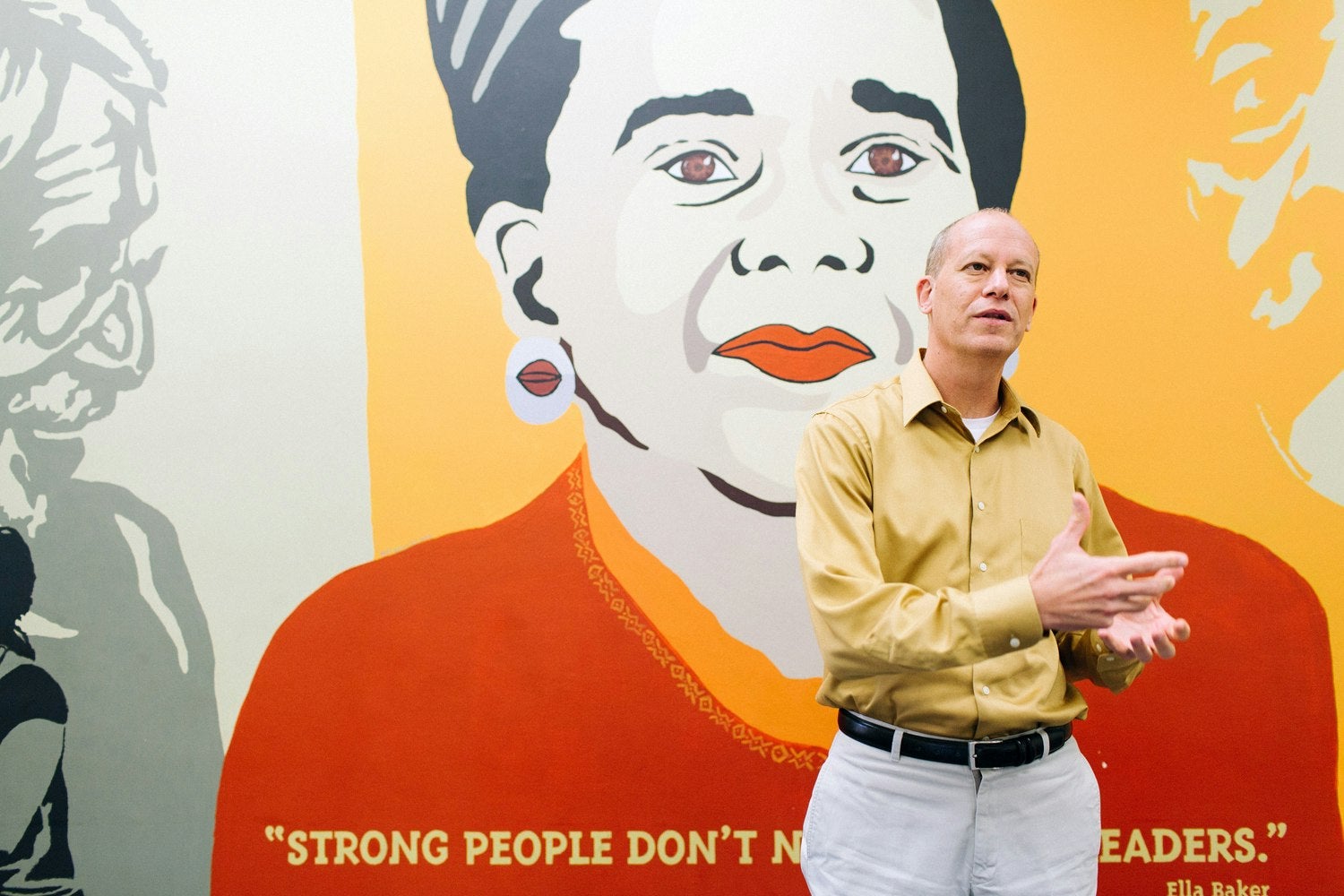

John Rogers is a professor of education at the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies and the director of the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education and Access (IDEA).