For most students, the ability to afford college is a primary concern. Access to financial aid is key to their participation in higher education. Fortunately, in recent years, changes to the application process, such as streamlining the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), have helped to reduce the complexity of applying.

But recent research by Joanne Do, a doctoral graduate of the UCLA Education Leadership Program, makes clear that for many students, challenges to accessing needed financial aid extend beyond the initial application process, increasing worry and taking a toll on student well-being.

Published as part of the recently launched UCLA ELP Dissertation Brief Series, the study, “How the Financial Aid Process Negatively Impacts Students,” explored how the financial aid process affects first-generation college students.

“This research is really about how the financial aid process affects students individually and personally, and the impact that process has on students’ experiences in college,” Do said. “I was really interested in seeing how the personal impact of some these processes that we put in place affects students.”

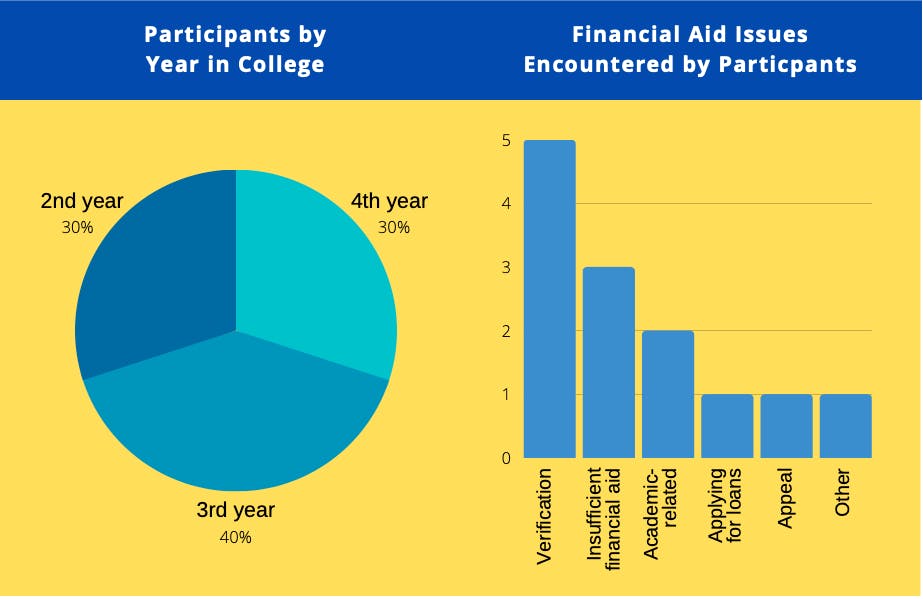

Based on interviews with 10 students, field observations of the financial aid office, and a review of forms and documents, the study contends that students face significant challenges with the financial aid process beyond the initial application. Students often are asked to provide proof of the information they submit, yet they struggle to understand and meet inconsistent institutional definitions of “adequate proof.” These same institutions also often flag students for additional verification and use complex jargon that is hard for students to understand, while placing the burden for accountability on students.

“Students are confronted with subsequent processes that prioritize compliance over their well-being,“ Do said.

Do’s study underscores how much time the focus on compliance adds to the financial aid process, prolonging student worry about their awards. And students reported that they received neither the support nor the resources they needed from their financial aid office.

“One participant really stood out to me,” Do said. “She was just tired. She was exhausted by the process. She was frustrated. It had just gotten to a point of fatigue, where she told me, ‘I don’t know how many times I need to be told and feel like I can’t afford school — that I don’t belong here because I can’t afford it.’”

The brief makes clear the toll on students. Students said their experiences with the financial aid process were dominated by fear, amplified by their own awareness of their first-generation status and need for financial aid. Students who dealt with the financial aid verification process said it was marked by an atmosphere of compliance and policing, furthering their feelings of anxiety, powerlessness, and diminished status.

“The students I interviewed were fearful of inadvertently making a mistake, of not knowing or understanding the rules and then breaking them and being held accountable for them.” Do said. “I think that was really amplified by the fact that they’re first-generation college students, so they don’t know what the rules are. They also fear that if they do something that compromises their financial aid, that’s it for them. They can’t afford to go to school, and their goals of attaining a degree and pursuing their future are going to be taken away from them.”

Do’s research springs from her own personal experiences as a first-generation college student.

“I just didn’t have very much knowledge or cultural or social capital to navigate even the application process. And when I was applying to college, my family and I were very naive about how much college would cost,” Do said. “We really weren’t prepared, and we didn’t get much help with financial aid. ”

After college, Do’s interest in the impact of the financial aid process grew while was working with low-income, first-generation college students. She saw how difficult the process was for students who had even fewer resources than she had as a student.

“I’ll never forget, I was standing in line next to a student I was trying to help at the financial aid office. And seeing the way this person in financial aid talked to him, spewing jargon at him, like she didn’t really care to understand what questions he was asking or what he was trying to,” Do said. “And the student, he just turns to me, and he says, ‘Do you hear the way she is talking to me? She’s talking to me like I’m stupid.’ And I just thought, ‘How could these processes be impacting students like this? A process that is supposed to help a student be able to afford to go to school?” That’s sort of where this research started.”

Do wants institutions to be more accountable to their students, and she hopes they will take up promising practices she has learned about in her research—simple things, like changes to language to make it friendlier and easier to understand, even including positive statements such as, “You belong here. You can do this. You belong at this institution.”

To improve their financial aid experience, students said they needed additional support and resources that are consistent, accessible, and attuned to their status as first-generation college students. Based on her study as well as her professional experience and understanding of the research literature, Do includes recommendations for equitable practices outlining steps that institutions, organizations, and policymakers can work toward to increase transparency, foster collaboration, reduce complexity and inefficiency, and create a culture of caring in financial aid.

“I think the most important thing about financial aid that I want people to understand is just how critical it is for so many students in order to access and succeed in college. Without it, many just won’t make it through,” Do notes.

“We need to remember these students are accessing aid because they want to go to college! And no student should feel like can’t go just because they can’t get access to their financial aid. Our institutions should really go out of their way to help students know what options there are, to help support students through that process, and to encourage their participation in school and make the most of their education.”

The full ELP Research Dissertation Brief, including more detailed recommendations is available here