Educational researchers and policy makers have had much to say about the issues around teaching children through the pandemic, with topics ranging from learning loss to safely returning to in-person instruction in schools. However, the voices of children themselves and how they have made sense of the pandemic has been noticeably absent from the public commentary.

Researchers at UCLA have sought to change that, with their classroom study conducted at UCLA Lab School titled, “¿Qué dicen Las/os Niñas/os? – What Do Children Say? Children’s Perspectives on Pandemic-related Remote Learning & Going Back to School.” Inmaculada Gárcia-Sánchez, associate professor of education and Marjorie Faulstich Orellana, professor of education worked with Elena Pérez, Ed.D., a dual-language classroom teacher at UCLA Lab School, to center the thoughts and feelings of children during the pandemic.

The research team worked with Lab School students in the Early Childhood II (ECII) Dual Language (DL) program,to find out what the children had been learning in remote classes, individually, and with their families; what they liked and didn’t like about Zoom classrooms; and how they made sense of the transition back to in-person learning. The study was aimed at capturing children’s perspectives during a critical juncture, as they transitioned to hybrid/in-person instruction after many months of learning remotely from March 2020 through June of 2021.

“The children had clear opinions about both the challenges and possibilities of Zoom learning,” Pérez noted. “Their views were centrally shaped by relationships: they definitely preferred being together in person, but because some kids couldn’t be in school in person for different reasons, some kids indicated that they liked Zoom better, because they could see ‘all of their friends’.

“When schools re-opened, they were very happy to be back with their friends in the playground,” Professor Orellana added, “But they told us that they got to enjoy doing other things at home that they couldn’t do at school, in other relationships: with their pets and family members.”

“Their views were both complex and pragmatic,” Professor García-Sánchez explained. “They didn’t like when the computer screens froze, or they got accidentally kicked out of the Zoom rooms. But they learned how to troubleshoot the problems and get back on – often stepping up to show others – including the adults in the room – how to do things with the technology.”

Professors García-Sánchez and Orellana worked with Pérez on designing and implementing classroom activities that elicited children’s perspectives, including weekly bilingual discussions about children’s feelings about the pandemic, their experiences with Zoom classrooms, and their understanding of safety rules upon return to school. These discussions were integrated with pedagogical aims, such as comparing and contrasting in-person vs. Zoom learning. All discussions were designed to support both English and Spanish learners in expanding their linguistic repertoires and aimed at supporting their social, emotional, cognitive, and linguistic development.

The researchers also turned to the children’s classroom work related to their topics, including “mapas de exploración” – maps of places where kids spent time during the pandemic, at home and beyond; drawings about feelings while “hiding” behind face masks; representations of acts of kindness that they gave or received during the pandemic; and photo-journals of their pandemic activities.

“We offered children a variety of ways to express their thoughts and feelings about the pandemic: in photos, drawings, and dramatizations,” noted Professor Orellana, allowing different ways into the issues.

Professor García-Sánchez added that, “visual arts, as a form of ‘play,’ allow for an imaginative space where the children were able to explore the complexities of the reality of the pandemic. And this, in turn, allowed for a more nuanced and deeper perspective from the children than sometimes we were able to get from interviews or group discussions.”

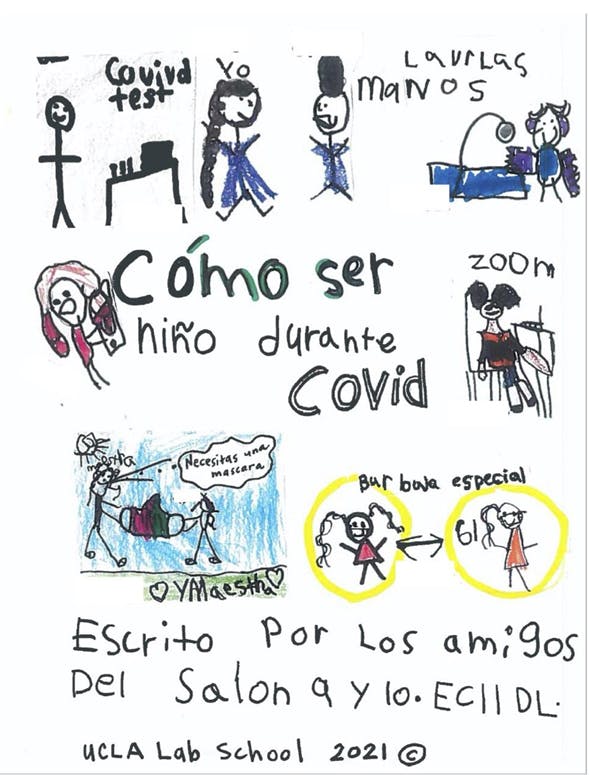

The visual arts component also strengthened children’s investment and leadership in the research project. After reading a book titled, “To Be a Kid” and discussing how kids’ activities had changed due to the pandemic, the children started making their own drawings of their realities and suggested to the researchers that they could write their own book on, “How to be a Kid During the Pandemic.”

Following the children’s lead over the course of several weeks, the researchers and the class brainstormed ideas, drafted, revised, edited, and published the book, “Cómo ser niño durante Covid.”

“This was one of the ways in which the pandemic became the ultimate project learning experience,” said Professor García-Sánchez. A celebration of the culmination of the project took place on June 10 at the UCLA Sculpture Garden.

Over the summer, the researchers will examine the children’s words and drawings, in order to think about their sense-making processes during this unprecedented time and to develop qualitative analyses to share in different forms for a variety of audiences including educators, policymakers, parents, and other children.

“For sure, the effects of the pandemic were inequitable: some children lost family members; some family members lost jobs; and other families seemed relatively unaffected, or had the resources to avoid its worst effects,” said Professor Orellana.

“But this was part of the learning experience,” added Pérez. “Listening to children was key for understanding how the pandemic was experienced by different kids and families, and using that understanding to cultivate empathy for each other and for other people in the world.”

Above: UCLA Lab School students enjoy the publication of their book, “Cómo ser niño durante Covid/How to be a Kid During the Pandemic,” in the UCLA Sculpture Garden on June 10.

Photo by Elena Pérez