Exploring the lives of youth in the of Rio has been the research focus of Veriene Melo, a UCLA doctoral candidate in the division of Social Sciences & Comparative Education (SSCE). Supported by a dissertation fellowship from UCLA’s Graduate Division and the Jorge Paulo Lemann fellowship from UCLA’s Center for Brazilian Studies, Melo has been gathering data for the last four years on the work of Agência de Redes para Juventude (Networks for Youth Agency), an organization in Rio de Janeiro that seeks to direct young people in the creation of projects to impact their communities, while giving them the tools and skills for city-wide engagement.

A native of Brazil, Melo has studied how Agência’s entrepreneurial education has changed the lives of youth in favelas by helping them explore the value of their own cultural capital and aspirations. The creation of projects in culture and arts, for instance, have led many of the program participants to finding ways to succeed personally and give back to their communities. No small feat, considering that youth face not only the challenges of poverty and crime, but the ironically-named “pacification” efforts by the state police, which has attempted to take control of territories controlled by drug factions for the past eight years but often resorts to racial profiling and extreme violence against young people.

“Roughly 60,000 homicides take place every year in Brazil,” says Melo. “The victims of half of these are young people, 77 percent of whom are Black. You may have nothing to do with what’s going on, but when you are a 19-year-old Black kid, you have to watch out a lot more so you are not in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Melo says that the lack of education and work opportunities – conditions that resonate within many urban communities the world over – forms a vicious cycle with no escape for these youth. A low quality public education is all that is available to most and only one-third of the population get to graduate from high school. Although Brazil’s public universities are considered the best in the country, students need a good basic education to pass the entrance exams, or have the ability to pay for a private university. In addition, there are large numbers of youth working informally or not working at all. These issues combined translate to a rate of young people being classified as NEETS (Not in Employment, Education, or Training) as high as 22 percent.

Melo says that building contacts with people who live in different communities, or having a family member who managed to achieve an education, are key to exposing young people to another way of life. She notes her own trajectory as an example.

“I grew up in the Baixada Fluminense in the state of Rio,” she says.”The region is considered very violent and is surrounded by a lot of impoverished communities.”

Despite her humble upbringing, Melo dreamed of exploring the world – an aspiration that became more tangible once she ventured beyond her community.

“My mom worked at a public hospital, and you could get a discount at university at that time, so I started attending college in Copacabana, which is a more affluent neighborhood I rarely frequented,” she says. “It would take me almost two hours to get there. One of my classmates, a girl who lived in the area, showed me that I could travel and study abroad and encouraged me to apply for a program. And that’s how I was introduced to a whole different reality – otherwise I would have stayed where I was.”

Melo did study abroad in summer programs at the Universidad de Granada and at the Alliance Française in Paris before achieving her bachelor’s degree in International Studies and Spanish at the University of Colorado, Denver. Thanks to a full fellowship from the Ayacucho Foundation, she went on to earn her master’s degree in Latin American Studies at Stanford University in 2012. Since then she has worked as a researcher at the Program on Poverty and Governance (PovGov) directed by Beatriz Magaloni, associate professor of political science at Stanford. In addition to an impact evaluation of Agência, she has been involved in projects that examine issues of police use of force and community perceptions of public security with a focus in Rio’s favelas.

“Rio’s police force is considered one of the most lethal,” notes Melo. “When making a comparison to the U.S. – they basically have a Ferguson [scenario] every day.”

“When conducting research in these communities the profound exposure to violence was really shocking to me,” she notes. “People there have a different understanding of it. I think if you live under that regularly, you end up becoming immune to it. That’s why it’s so hard to ask questions on this topic because they are based on what researchers think violence means.”

Melo says that despite living under these almost unimaginable conditions, youth who have participated in Agência have been able to realize that they can find paths to achieve their potential. She says that her in-depth interviews have revealed, amid the harsh lifestyle, “an excitement from when the program came into their lives and how it changed how they view everything around them.”

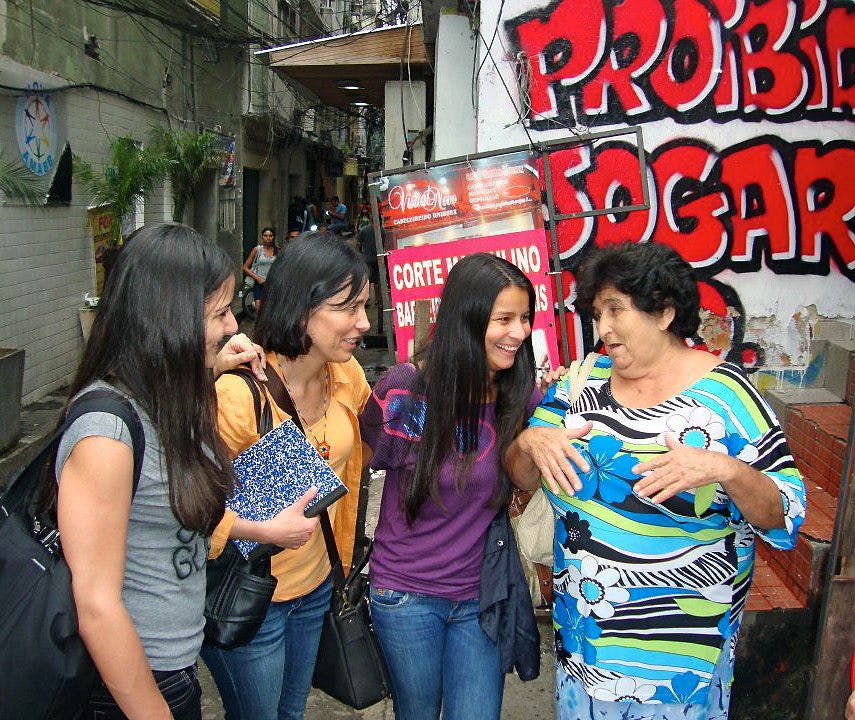

“That’s why I think the work Agência does is so important,” says Melo. “What they propose is that youth create projects to impact the community, based on their views of what its most important needs are. They introduce them to people who are doing things across the city, who are people they would never ordinarily meet. That opens up so much in terms of the way you view yourself, what you can do, and what is possible.”

Melo underscores how Agência’s successes can be attributed to how the program respects what favela youth bring to the table, an approach she is attempting to connect to the critical pedagogy of Paulo Freire in her dissertation under the supervision of UCLA Professor of Education Carlos Alberto Torres.

“There are [social] programs that come in from the outside, with a fixed ‘recipe’ on what to do,” Melo says. “I’ve always been interested in critical pedagogy and working with people, trying to understand what their necessities are, listening to them, and recognizing their knowledge. Nobody knows better the issues they go through than the people who live in those spaces.

“A critical education empowers people. It helps them understand their position in society and work upon their knowledge in order to change it,” she says. “I want to understand the impact of programs that don’t come in with a fixed agenda and that open up a space for local cultural wealth to flourish in people’s lives and communities.”

Last November, Melo joined the International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University in Rotterdam as a visiting fellow. She engages with faculty members and researchers from the Civic Innovation Research Initiative as she completes her final year of writing her dissertation.