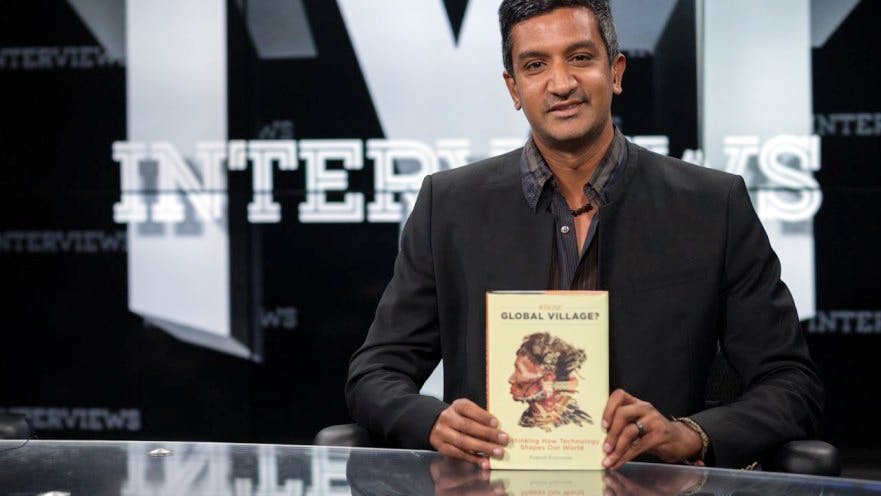

In his study of the connections between technology, politics, and society across the globe, Ramesh Srinivasan has explored revolutions in Egypt and Kyrgyzstan, the role of digital media in supporting indigenous and non-western communities across the world, including fieldwork within Native American reservations, Bolivia and the Oaxacan region of Mexico. He is one of the foremost critics of top-down black-box technology as one can see in relation to his many appearances critiquing Facebook as a form of news, the cultural biases of algorithms, and more. In sharing his findings through a variety of outlets including the Washington Post, CNN, Fusion, MSNBC, TED Talks, Al Jazeera, and National Public Radio, Srinivasan helps imagine a new future for the internet more in line with the experiences and agendas of its diverse users. (For Srinivasan’s press links, click here.)

In his new book, “Whose Global Village? Rethinking How Technology Impacts Our World” (New York: NYU Press, 2017) Srinivasan, a professor of information studies at UCLA and founder of the UC Digital Cultures Lab, points a way forward past the echo chambers, filter bubbles, and black boxes of today to an environment where companies like Facebook and Google better serve the public interest. His work has been publicly supported by major figures such as Arianna Huffington and Van Jones.

Srinivasan has been on the UCLA faculty since 2005, in the Department of Information Studies and in the Department of Design Media Arts. In 2015, he established the UC-wide Digital Cultures Lab, exploring the meaning of technology worldwide. Professor Srinivasan earned his Ph.D. in design studies at Harvard; his master’s degree in media arts and science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and his bachelor’s degree in industrial engineering at Stanford. He has served fellowships in MIT’s Media Laboratory in Cambridge and the MIT Media Lab Asia. Srinivasan has also been a teaching fellow at the Graduate School of Design and Department of Visual and Environmental Design at Harvard.

Ampersand

Ampersand: How, in your opinion, has the digital landscape evolved?

Ramesh Srinivasan: We’re at this point right now where the promise of the internet as a fundamentally democratic space is endangered. It’s important to remember that the internet first started on many levels as a community network. The first online communities were actual counterculture communities – generally in Northern California. They were not only virtual communities like Facebook and other social media are today. It was about focusing on a group of people that shared a culture, identity, and values.

As the scale of the internet expanded – there are now three to four billion people on the internet, mostly through their mobile phones – the challenge [became] how to develop technologies to connect people on that incredible level of scale, with an eye to economic gain. In so doing, organizations from search engines to social network companies started to recognize that the best thing they could do is develop various sources and systems to analyze and connect people across their data.

&: How did this distort the original “grassroots” origins of online communities?

Srinivasan: The notion of community where people are speaking to and learning from one another has increasingly been replaced by sort of an invisible and out-of-touch manner through which users are engaging with the larger world. We don’t always know how the information that comes from our fingertips is curated or selected, how it’s chosen, or what data is being collected about us. All of these are mechanisms over which users have no control.

&: How does this play out in today’s political climate?

Srinivasan: There is an incredibly important democratic challenge to the way that the internet has been co-opted by a limited number of political and commercial forces. Our social network systems are generally made up of people with whom we have political similarities. We confirm our own biases through those systems and algorithms. Social media provides the perfect conduit to actually divide the American public and engage with the sorts of sound-bite comments that Trump and his administration are making.

Increasingly throughout the world, people are experiencing the internet through platforms that are black boxes, specifically, Facebook and Google. Those platforms have become our gateways not only to the larger digital world but to the world of news itself.

There are over 1.8 billion users of Facebook and about the same with Google. People are under the impression – although now less so with the election – that those systems are allowing them to connect to the wider world. And on some level, it is. But on a lot of other levels, those systems are actually locking us down and blocking us from understanding one another.

&: How can the internet be restored to its original purpose of providing access and information to audiences of more diversity of thought, culture, and purpose?

My book looks at positive and I hope, inspiring examples by which technology, new media, and the internet have worked together successfully. I’ve done collaborations with a number of diverse communities, from political activists and movements like Black Lives Matter, to villages and rural communities around the world that are rarely thought of when we think of the internet, because they’re so often misunderstood.

The largest internet in terms of language in the world is totally disconnected from the English language. There’s a whole Chinese internet existing in parallel. I’m not saying that it needs to be connected to the English language internet, but our assumptions of what the digital world is from a Western perspective is challenged by what is happening in China. This adds to the complications I’m describing.

There has always been this tension whether [social media] is a public space and/or utility or whether it was to be co-opted by private organizations or companies. I’m not asking companies like Facebook or Google to actually publish their software codes for how they are connecting us or not connecting us, but I am asking them to give us some choices as we experience the digital world.

Google and Facebook provide incredibly valuable services. But those services shouldn’t be a contract where we have no power over the experiences they provide for us. The internet needs a revolution where we think about how it’s designed, whose agendas are served, and how potentially it empowers us to have better, more humane conversations with one another.

Photo courtesy of rameshsrinivasan.org