Brian Belak, a first-year MLIS student in UCLA’s Department of Information Studies, has written a blog post for the UCLA Library’s Preservation Blog on “Jazz in Synanon,” based on his work this Spring of processing a large 16mm film collection within the UCLA Library’s holdings of the Synanon Foundation Records, which chronicle the controversial drug rehabilitation organization that was founded in Santa Monica in 1958. As an AV Scholar in the UCLA Library’s Center for Primary Research and Training program, Belak is working on copies of documentaries made by others about Synanon and their radical methods of rehabilitation, home movies and amateur and student films made in the internal Synanon schools, and self-documentation of Synanon activities, presented in “Synanon on Film” newsreel-like updates.

“The Synanon Foundation Collection overall is a vast document of an experimental and therapeutic community whose influence continues to register today, even after its demise and current reputation,” says Belak. “Many rehabilitation groups that sprung up later traced their techniques to those that Synanon pioneered in the 1960s, in particular the Synanon ‘Game’ of group encounter therapy.

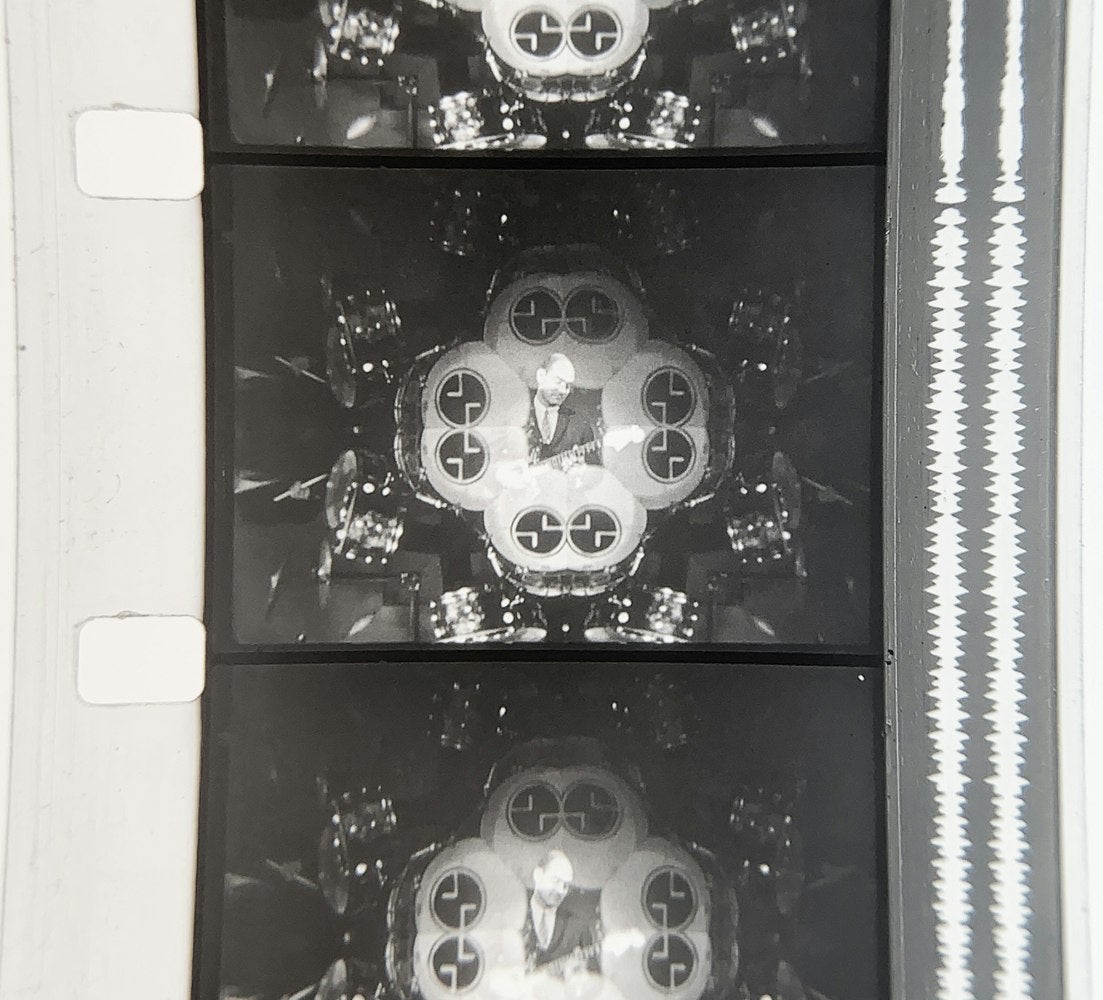

While viewing the collection’s reels to assess their condition, standardizing film titles and finding their relationships to each other, and rehouse the films into archival storage, Belak noticed Synanon’s interconnections with the history of West Coast jazz in the 1950s and 60s. As drug use was prevalent among musicians of the genre, a number of Synanon members formed a “house band” that became well-known among non-addicts, many of whom were prominent figures in Hollywood whose connections lent themselves to Synanon’s success at that time. The impact of this was such that the short-lived Pacific Jazz label produced the album, “Sounds of Synanon,” which was the recorded debut of guitarist Joe Pass.

Belak says that while the majority of research requests on Synanon tend to seek overviews of substance abuse treatment and group psychotherapy, a closer look at the reels uncover more of the day-to-day history of the program, including the impact of its connection to jazz musicians.

“The “Jazz in Synanon” blog post grew out of a number of connections I started making as I looked through the films this year and saw music, specifically jazz, come up repeatedly across the years,” he says. “Drug abuse was endemic to parts of jazz music in the 1950s when Synanon first started, and it seems there was a mutually beneficial relationship between the earliest musician residents and the foundation. For a musician like Joe Pass, whose reputation would only continue to grow after leaving Synanon, to have a debut album under the name “Sounds of Synanon” meant significant promotion for the foundation in its early years.”

Belak says that Synanon’s connection to the jazz genre could uncover a great deal of internal knowledge about other drug rehabilitation programs and their effects upon residents – and vice versa.

“I think more research could be done to establish the full network of musicians that were involved with Synanon over its history, as well as connections to other rehabilitation organizations with jazz associations like the Narcotic Farm in Kentucky,” notes Belak. “Synanon specifically held a number of core beliefs and philosophies, at one point declaring itself a religion, so to connect the musicians associated with it could reveal aspects to their practice or collaborations, depending if they stayed only for a short time or became lifelong residents.

“Synanon was [also] considered relatively unique for its support for interracial relationships within the community, including the founder Chuck Dederich and his wife Betty. By emphasizing that culture, there might be a way that Synanon affected or reflected the attitudes of the musicians that lived there and who they collaborated with.”

Although Belak has not been able to work with the films for several months due to the COVID-19 pandemic, he has continued to work remotely on the Synanon collection as well as other AV collections for the UCLA Library, including interviews within the Ephraim Sales Collection of Tapes and Transcripts of Interviews by Roy Newquist, that includes conversations with prominent writers such as Gwendolyn Brooks, Harper Lee, and Madeleine L’Engle. Belak is working on formatting and updating metadata for the library catalogand translating the inspection notes and description of the physical film conditions into information that will aid researchers in accessing the collection from afar. He says that he misses working hands-on with the films and that a great deal of work remains to complete processing the entire Synanon collection.

Before arriving at UCLA, Belak served as collections manager for Chicago Film Archives, an independent, regional film archive that focuses on preserving Midwestern history on film.

His responsibilities included managing the intake and processing of new collections while working with filmmakers and researchers to provide access to the archive’s collections.He says that he was attracted to UCLA IS because of the stature of UCLA in the field of audiovisual preservation, particularly in terms of faculty and connections to the profession, including the UCLA Film and Television Archive.

“My work at Chicago Film Archives had provided me with opportunities to gain practical experience and begin to raise critical questions, but I was looking for space to establish a stronger theoretical foundation for my preservation work,” he says. “By committing to non-mainstream forms of filmmaking like avant-garde, industrial, amateur, and home movies, I think the archive is a valuable resource for direct, intimate views of the past [and] emphasizes the significance of local archives and collections.

“[Chicago Film Archives] is a very public space, with people regularly coming in to look at collections or bring their own films for digitization or preservation,” says Belak. “I learned a lot from talking with them and connecting with how they wanted their personal histories treated and kept accessible. UCLA’s emphasis on social justice and ethical approaches to archival work has been inspiring, and the faculty have created valuable opportunities to put community-based work alongside and within the academic program.”

To read Belak’s full post on the UCLA Library’s Preservation Blog, visit this link.

Courtesy of the Charles E. Young Research Library