The SEIS interdisciplinary partnership collaborates with the Organization for Social Media Safety, as part of UCLA’s campus-wide Initiative to Study Hate.

Researchers in the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies are collaborating with the Organization for Social Media Safety (OFSMS), a Los Angeles-based nonprofit centered on protecting users of social media – especially K-12 students – to study the occurrences and impacts of online hate speech on adolescents.

Co-led by Wasserman Dean Christina Christie and UCLA Professor of Information Studies Anne Gilliland, the Social Media and the Spread of Hate (SMASH) project is analyzing data about students’ exposure to hate speech on social media gathered from students at more than 40 schools across the country that are participating in programming by OFSMS. The project will also conduct focus group discussions with students in four Los Angeles schools. The research team includes Christine Ong, research scientist, CRESST; Arif Amlani, SEIS director of new initiatives; Mark Hansen, SEIS assistant professor-in-residence and research scientist, CRESST; and Marc Berkman, chief executive officer, OFSMS. Tyrone Howard, UCLA professor of education, will serve as advisor on the project.

UCLA Wasserman Dean Christina Christie

“Use of social media amongst children and young adults has increased exponentially in the last two decades,” says Dean Christie. “Yet, we understand so little of its effects and how it is impacting the lives of our new generation. Our partnership with the Organization for Social Media Safety enables us to research these effects through data collected from responses of thousands of students and from school administrators nationwide.

“We expect that this particular study of hate on social media will be the genesis of a full research program in SEIS on the impact of digital media on students’ lives. By understanding this impact, we can be better prepared to devise curricula and pedagogy that can address these effects.”

The SMASH project is part of the University’s interdisciplinary Initiative to Study Hate, which brings together UCLA scholars and external partners through a number of research collaborations with the aim of better understanding and ultimately mitigating hate in its multiple forms. The SMASH study is among 23 projects to be funded in the first year of the Initiative, supported by a $3 million gift to the University from an anonymous donor.

“The UCLA Initiative to Study Hate builds on the information and media literacy efforts that have been ongoing in schools and libraries,” says Professor Gilliland. “It’s a topic that both departments in Ed&IS have been concerned about for a long time. We have spent the last three years developing and implementing a new undergraduate minor in information and media literacy, and with the Department of Education as well as OFSMS’s connections to schools, we have unique resources to ask young people about their experiences with social media. It allows us to bring to bear all the expertise that we collectively have on a topic that has been recognized as a national priority.”

UCLA Professor of Information Studies Anne Gilliland

SMASH is examining hate speech on social media experienced by adolescents through data gathered by the OFSMS, which holds assemblies on social media safety at schools across the nation. It is also exploring how exposure to hate speech varies among school types (e.g., private vs. public), student demographics (e.g., race/ethnicity, grade level), and overall use.

The initial focus of the SMASH project is on understanding what youth perceive as hate speech or hateful content, their levels of exposure, and the kinds of exposure. OFSMS findings to date show that over 80% of students self-report having been exposed to hate speech on social media. Data from the Pew Research Center reveals that 35% of teens say they use YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, or Facebook, “almost constantly,” with Black and Hispanic teens more likely than White teens to report being almost constantly on TikTok, YouTube and Instagram.

Pew also found that 54% of teens have said it would be hard to give up social media, and 46% of teens say they have experienced cyberbullying, including offensive name calling, rumors, and receiving explicit messages and physical threats. Gender has been found to play a role, with teen girls more likely than teen boys to say they have been cyberbullied because of their appearance (17% vs. 11%) or their gender (14% vs. 6%).

“This study is a first step to understanding more about what’s happening and how students conceptualize or define hate speech,” says Ong. “It’s important to gather their views.”

Christine Ong, research scientist, CRESST

“The larger frame here is what are the effects of hate speech on young children and adolescents,” says Amlani. “As a preliminary study towards that eventual goal, this study looks at the extent of exposure, definitions of hate speech, and importantly, the media through which adolescents are exposed to hate speech. What makes this research powerful is that through the Organization for Social Media Safety, we have access to a large student population because of the assemblies that they hold, which could be anywhere from 50 to 100 assemblies a year, with 400 or 500 students in each of those assemblies. That’s a large population from which to conduct research.”

Using this study as a springboard, SMASH aims to continue to address critical questions such as whether or under what conditions certain groups are at greater risk from exposure; the impact of school polices on propagation of social media related harms; and the efficacy of various interventions. The study will also lay a foundation for future studies of how hate speech on social media affects adolescent mental health, learning trajectories, and educational achievement, as well as monitoring trends over time in schools across the United States.

Professor Gilliand, working with a team of undergraduate researchers, recently conducted several studies examining anti-Asian hate speech on Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic. She says that the SMASH study will reveal closer definitions of what hate speech and content mean to different generations.

“That’s actually the fundamental question we have to answer first, and I would say that’s the question that all the projects that are funded through the UCLA Initiative to Study Hate are grappling with: How do people of different ages, in different circumstances, and in different disciplines define hate?” Gilliland says. “Because if you can’t define what you’re grappling with, it’s really hard to counter it.”

Gilliland currently teaches in an undergraduate cluster course in modern political violence that examines political and inter-ethnic violence through the histories of the Holocaust, the Guatemalan genocide that lasted from the 1960s to the 1990s, and the wars in Croatia and Bosnia in the 1990s. Drawing a chilling parallel between how propaganda fueled these atrocities, she says that the SMASH study can similarly support learning around, “… how people were motivated, how they were taught to hate and how they were motivated into discriminatory and bullying behaviors that ended up as outright violence, tragedy, and genocide.

“This is why teaching history is so important,” says Professor Gilliland. “Adults understand speech acts within particular historical and experiential contexts. Topics of conversation and speech acts more generally are meaningful to younger people in different ways but often without the same degree of context. It is important to build that historical and contextual awareness in young people going forward.”

Amlani says there is the hope that the SMASH study will provide a more focused look at how the spread of hate speech on social media has become a danger for adolescents that until now has been acknowledged, but not formally studied.

“The larger context for us is social media and general well-being, which would include other things that our youth are faced with,” he says. “I’ve felt for the last few years that we’re really playing catch up on consequences that we are witnessing from the use of the internet, and we haven’t intentionally focused our attention on what might be forthcoming issues, both in terms of the enormous possibilities and the perils that the internet holds. We hope that this study progresses into looking forward and identifying potential negative effects so that we are able to put measures in place to mitigate those effects earlier on, rather than after the fact.”

Ong says that the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on social media use would make a thought-provoking study in the future.

“Putting my parent hat on… our world changed,” she says. “All these tools have been put in people’s hands, and it’s not going back. The hope is that this study will inform a much larger and longer body of research that explores both the impact of the pandemic and how to be more thoughtful and forward-thinking about adolescents’ use of social media. There’s a focus on technology and social media in current conversations, but it also comes down to adolescents’ ability to be reflective, think critically, and show empathy. These are really important skills that go across all facets of life.”

Ong notes that the student-centered nature of the SMASH study will be an advantage in answering the complicated questions about hate speech and its impacts on youth.

“Speaking for myself as a researcher, there is a big learning curve in figuring out how to talk about these issues in a productive and meaningful way,” says Ong. “These are really important, but difficult issues. What’s so powerful about this work is our commitment in gathering student voices and hearing from them directly. They’re both the consumers and the producers, really at the center. They deserve to have a voice at the table.”

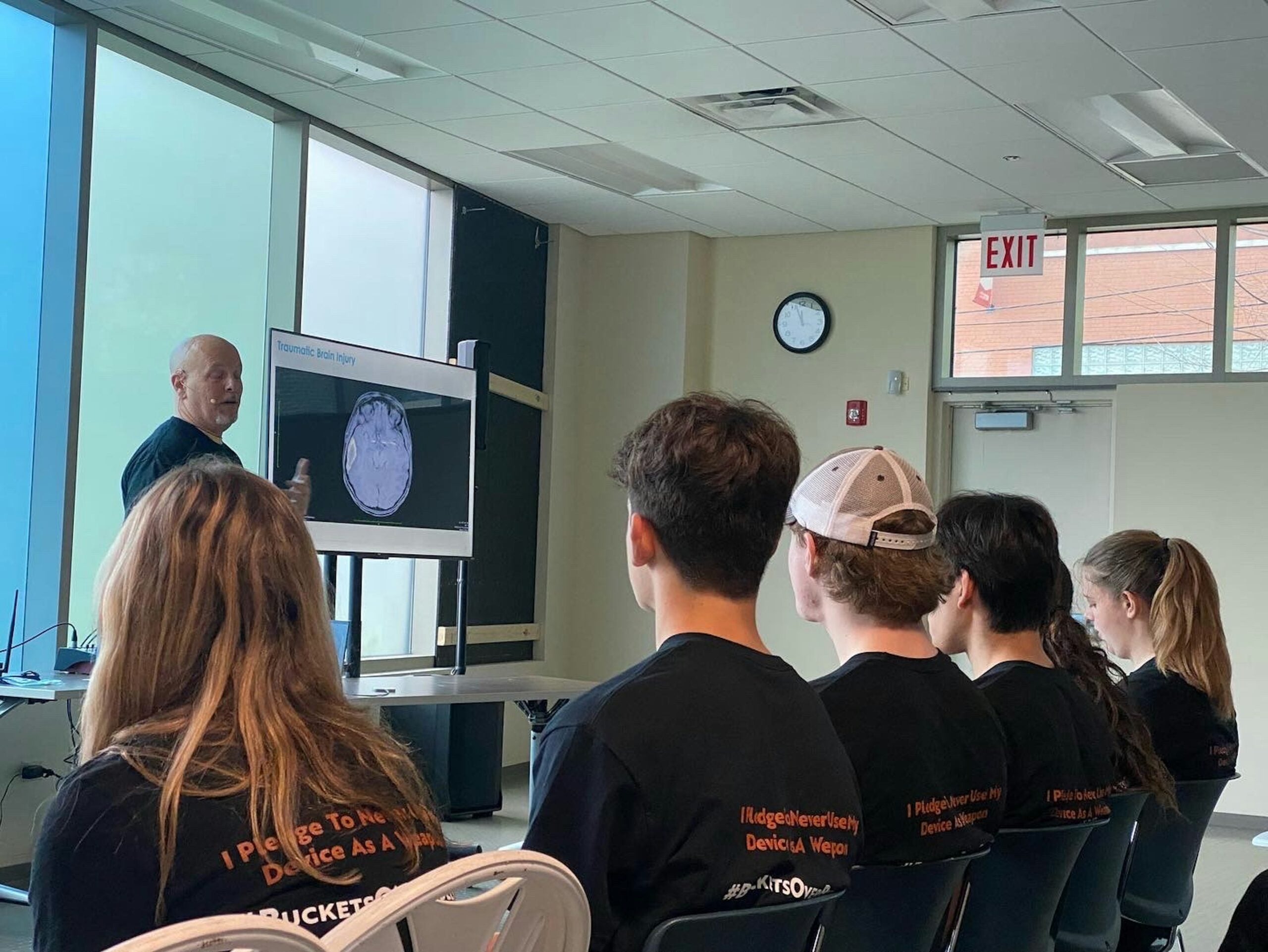

Above: The Organization for Social Media Safety holds assemblies for schools across the nation in order to build awareness of social media safety among students, educators, and families.

Courtesy of Marc Berkman, OFSMS