Mike Rose has spent decades teaching in and studying a wide range of educational settings, from elementary school to adult literacy and job training programs. In a new paperback edition of his 2009 book, “Why School?” Reclaiming Education for All of Us” (New York: The New Press: 2014), the UCLA professor of education takes an in-depth look at the ideals of a democratic education, with added information on hot-button issues such as Race to the Top, Common Core, and the increased role of business in school policy. The new edition also explores Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs), the popularity of character education, and the relationship between adult education and poverty.

“We live in an anxious age and seek our grounding, our assurances in ways that don’t satisfy our longing—that, in fact, make things worse,” posits Rose in a recent blog post. “We’ve lost hope in the public sphere and grab at market-based and private solutions, which undercut the sharing of obligation and risk and keep us scrambling for individual advantage. Though we pride ourselves as a nation of opportunity and a second chance, our social policies can be terribly ungenerous… We’ve narrowed the purpose of schooling to economic competitiveness, our kids becoming economic indicators. And we’ve reduced our definition of human development and achievement—that miraculous growth of intelligence, sensibility, and the discovery of the world—to a test score.”

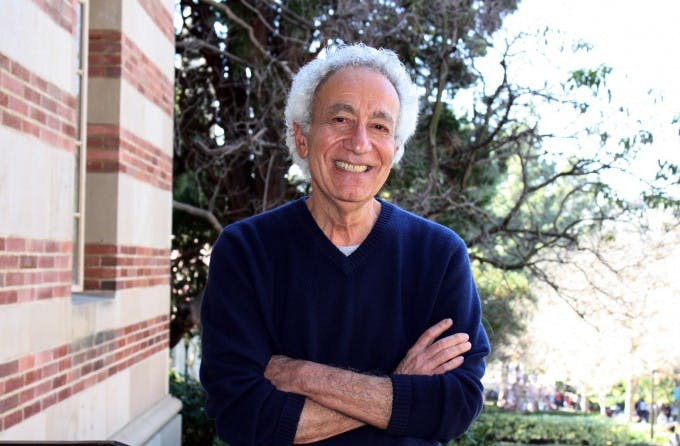

A research professor in the Social Research Methodology Division (SRM) of the UCLA Graduate School of Education & Information Studies, Rose is a member of the National Academy of Education and the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Grawemeyer Award in Education. He has received awards from the Spencer Foundation, the National Council of Teachers of English, the Modern Language Association, and the American Educational Research Association.

Rose has appeared on more than 200 national and regional radio and television outlets, including Fresh Air, Bill Moyers’ World of Ideas, Studs Terkel, NPR Weekend Edition, and Tavis Smiley. He is a regular contributor to the Washington Post’s education blog, “The Answer Sheet” by Valerie Strauss. His previous books include “Possible Lives: The Promise of Public Education in America,” “The Mind at Work: Valuing the Intelligence of the American Worker,” and “Back to School: Why Everyone Deserves a Second Chance at Education.”

Ampersand had the opportunity to speak with Professor Rose on the new edition of “Why School?” as well as on the impact of high-stakes testing on curriculum, the role of education at the core of a democracy, and the importance of the writing we do about education.

Ampersand: What are some of the major changes to education since the first edition of “Why School?”

Mike Rose: Since 2009, we’ve had the emergence and dominance of Race to the Top, the Obama administration’s federal education policy, and of the Common Core State Standards. We’ve also had the increased involvement of very big philanthropies, high-tech entrepreneurs, and venture capitalists. For example, there’s a current lawsuit in California, funded by a Silicon Valley executive and the Broad Foundation, among others, that, if successful, would change the laws concerning teacher tenure and seniority protections.

Another development is the resurgence of character education, that is, a renewed interest in trying to teach children certain character qualities like perseverance, flexibility, positive thinking, and, the new buzzword, “grit.” The focus of character education these days is on poor children, the idea being that if they had more of these characteristics, they would fare better against the assaults of poverty.

Character education is part of any educational system. If you look at the McGuffey Readers that were used in the United States in the 19th Century, they are imbued with ethical maxims. It’s a good thing for schools to be concerned with the development of traits like perseverance and flexibility, of course. What concerns me about the current rush to character education is that it, in some cases, is offered as a solution to the achievement gap. So instead of policy to address poverty, we have these educational and psychological interventions for poor kids.

Overall, my biggest concern, the central idea of “Why School?,” is that the purpose of education in the United States has gotten so narrow. Education is more than just a technocratic and economic enterprise, which is the message you get from the educational policy that has been in place for several decades. Everything you read from the state or federal government justifies education for its economic payoff, both for society and the individual. National reform movements have promulgated technocratic fixes, whether through standardized test scores, quantitative methods to evaluate teachers, or ways to structure schools that are more in line with management principles than educational principles. A whole generation has come of age not hearing any other way to think about school.

I try to offer a vision of schooling that includes the economic component—we want our children to be able to work, to survive economically. But I also want to remind us of all the other reasons that we educate, from personal development and finding out who one is, to being able to participate more fully in society as a literate and numerate citizen. And what about the nurturing of curiosity, exploration, creativity, or the willingness to take a chance, to venture a different kind of answer? The subtitle of the book is “Reclaiming Education for All of Us.” I try to reclaim these broader purposes of education.

&: How has the focus on high-stakes testing diminished the education experience?

MR: I realize that the testing regimes of No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top have probably jolted some poorly performing schools and districts to reassess what they’re doing and try something new. But overall, I think that the negatives outweigh the positives. We have research evidence that in some places the pressure to raise test scores in reading and math has led to a compressed curriculum: social studies, for example, and even science get less coverage. And music and art can be put aside all together.

Related to this issue of the compressed curriculum is the manner of teaching. The testing regimes often bring with them scripted and constrained ways of teaching—really, in some cases, scripts that teachers must follow. Now if you’re a new teacher and are feeling adrift, it can be useful and comforting to have such direction, though that direction if extreme can also limit your chances to grow. But overall this manner of directing and scripting teaching reduces the possibility of the spontaneous and creative—following the lead of ideas and questions that come from your students. It takes a pretty experienced and skillful teacher to be able to comply with the script and also maintain the creative potential of the classroom.

&: Why is access to education for all the core of a democracy?

MR: Well, multiple reasons. There’s the basic idea that to be able to participate as a citizen, you need access to information, you need to be informed. These days that means being able to filter through an overwhelming amount of information, being able to make judgments about the quality of that information, its source, the way it fits with or is at odds with other things you know. To be that informed citizen you need to be literate and numerate, know something about history and science and world culture and geopolitics, know the basics of how government functions. But hand in glove, you need to be able to think with all this knowledge. Did your education equip you to not just know things but use what you know, probe with it, speak up with it? To revisit what we discussed earlier, you won’t hear these goals mentioned in most official documents and speeches about education. And that concerns me.

&: Finally, you write a lot in this book about the language we use to discuss education and even have a chapter on writing about school. Why is that?

MR: The language we use also matters. In all my teaching, I place huge emphasis on writing well and carefully. So I thought it would be helpful to include in this edition some advice about writing.

On a broader level, the language a society uses to discuss schooling helps define schooling. It shapes education policy and it shapes the way we think about what it means to be educated. In an early chapter in the book, I ask the reader: “When was the last time you were moved by a high-level speech about education?” I take a guess that it’s been quite a while. Our policy talk is bloodless. It has no heartbeat to it.

I worry that the dominant vocabulary about schooling limits our shared respect for the extraordinary nature of thinking and learning, and lessens our sense of social obligation. So it becomes possible for us to affirm that the most meaningful evidence of learning is a score on a standardized test, or to reframe the public good in favor of fierce and unequal competition for a particular kind of academic honor. Education is reduced to a cognitive horse race.

We can do better. We have to.