Ananda Marin, a UCLA associate professor of education and the daughter of a jazz musician, studies the ways that artists improvise and how collaboration and community can transform education.

As a learning scientist, Professor Ananda Marin draws upon Indigenous ways of knowing and sociocultural theories to develop research on learning across everyday activities such as walking through a forest, and professional realms of knowledge such as teaching and musical performance.

Marin’s study “Reimagining Teaching/Learning Relations Alongside Improvisational and Ensemble Performers” is funded by a Spencer Foundation Large Grant. The study draws on co-design methodologies and how research collaborators (i.e., improvisational artists) play a central role in designing research activities. The study focused on jazz artists Hamid Drake, Michael Zerang, Lisa Alvarado, Joshua Abrams, and Zahra Baker. In addition, research activities have been conducted with the support of Brenda Lopez, research associate and media coordinator at the UCLA Center for Critical Race Studies in Education, Lindsay Lindberg, a doctoral student researcher in the Urban Schooling Division, and Shivani Davé, a doctoral student researcher in the Social Research Methodology Division.

Last April at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), Lopez and Marin presented the team’s findings in a Vice-Presidential Session on “Consequential Futures: The Contested Pursuit of Truth in Freedom Dreaming.” Their presentation, “Freedom Dreams Nested Within the Small Stories of Improvisational Jazz Artists,” explored the ways that artists develop their expertise, how the arts are a nexus for social, political, and ethical discourses in regard to education, and how freedom dreams often germinate in collaborative and improvisational contexts.

Family dynamics play a significant part in this strand of Professor Marin’s research. Her father is Hamid Drake, a jazz drummer and percussionist who has worked in various ensembles with luminaries such as Fred Anderson, Don Cherry, Jim Pepper, Herbie Hancock, and Pharoah Sanders. Drake is widely regarded as a top percussionist in jazz and improvised music, incorporating his interest in Afro-Cuban, Indian, and African percussion instruments and influences. Marin leverages her unique connection to this community with a study that illustrates the intrinsic value of the arts, not only as a subject to be studied in schools but as a discipline with routine practices that can inform how the field of education understands humans’ diverse capabilities as well as relationships between humans and the more-than-human world.

Marin is an associate professor of Social Research Methodology in the UCLA Department of Education and a faculty member in UCLA American Indian Studies. Her research explores the cultural nature of development with an emphasis on how processes for knowing (e.g., attention, embodiment, collaboration, etc.) vary across multiple communities, generations, and knowledge systems, and how educators can draw upon that variation in the design of teaching/learning environments.

Professor Marin achieved her Ph.D. in learning sciences at Northwestern University; her M.P.P at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University; and her B.A. in sociology at Yale University. Her accolades include the University of California Humanities Research Institute Residential Research Group Fellowship, the International Society of the Learning Sciences Early Career Award, the Lena Astin Faculty Mentoring Award from UCLA, and the Mellon Distinguished Scholar at the Center for Imagination in the Borderlands from Arizona State University. Recent publications include the article “Ambulatory sequences: Ecologies of learning by attending and observing on the move” for the journal Cognition and Instruction, and the co-written chapter, “Enacting relationships of kinship and care in research and educational settings” (with UCLA’s Nikki Barry (McDaid) for the 2020 book, “Critical Youth Research in Education: Methodologies of Praxis and Care,” co-edited by UCLA professor of education Teresa McCarty and published by Routledge.

Ed&IS Magazine: What inspired your study of improvisational jazz artists?

Ananda Marin: I decided a long time ago that I wasn’t going to seek out a research site solely for the sake of doing research. As a qualitative methodologist, I believe that relationships are extremely important to doing research, and I usually begin a research project with people that I have relationships with or by asking myself who I want to develop relationships with. With that comes some accountability to how we share and engage in the work, how we talk about it, and write about it.

I’m studying the arts in order to better understand collaboration and improvisation, two processes that are central to teaching and learning. I grew up in a family of artists and educators. My dad is a jazz percussionist and for many years, my mom was a dancer. My sister was a dancer. My niece dances. My grandmother was a piano teacher. My other sister was an English, ELL, and Bilingual teacher. My husband was an early childhood educator, a rap artist, and now makes Native American horror movies.

I would go and watch my sister perform and my dad perform. I noticed that the communities they were in were very different from the way we organize teaching and learning in schools. My participation in those communities shaped this current project and how I approached previous work on the role of the body in teaching and learning.

Ed&IS: What qualities do some of these communities have that aren’t typically present in education?

Marin: This project is guided by a couple of questions. One, I was interested in how people’s histories of relations influence their development over time, and then at a micro level, because part of what I do is study core cognitive processes like attention and embodiment, I was interested in the moment-to-moment of performance, when people are improvising [and] how they attune to one another.

I had spent a lot of time on the periphery of artistic communities. This led me to have a general sense that many of the folks I knew would probably say that even though they are viewed as experts and have contributed to and influenced their field, school was not a place where they developed that expertise. In addition, I would broadly argue that as a society we do not organize classroom environments to facilitate generative long-term relationships. In contrast, the artists who are involved in this project have long-term relationships with one another that span 10, 20, or 30 years, where they work together in different configurations [that] they’ve gone in and out of. How artists develop and sustain relationships and how relationships feed their own creative processes is of interest to me.

Ananda Marin, UCLA associate professor of education, leveraged the stature and relationships of her father, free jazz musician Hamid Drake, in order to conduct her research. Photo by Brenda Lopez

Ed&IS: How did your familial connection to this community impact your study?

Marin: My dad has been in the music performance world, what music critics call the jazz world, since he was 13 years old. I think the collaborating artists said yes to the project because they had a relationship with my dad. It’s not that they wouldn’t have said yes if I had asked them, but I think that relational connection was important. I think they saw the project as an opportunity to learn new things about each other, to get together, to perform together and have conversations that would move their own understanding of their craft in new ways.

Indigenous education scholars often ground their work in the 4 Rs and now the 5 Rs. These practices include respect, reciprocity, responsibility, relevance, and relationality. I knew [that] going in, if people were going to participate, relationality, reciprocity, and responsibility were going to be key factors. My father would also include reverence, which is related to respect, as a practice. He has pointed out to me that you have to have a certain reverence for what you do, and for what others before you did.

Ed&IS: How does this study address your interest in embodiment and physical space?

Marin: I would say that the majority of schools have been designed in ways that are about restraining our bodies versus tapping into the potential of freely using our whole bodies. This is particularly true when it comes to how the bodies of indigenous, Black, and Brown youth and youth from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are constructed in relation to schooling. However, when I have observed improvisational jazz performances, it was very clear to me that artists were using their whole bodies to support their own processes for learning and creativity. I want to understand how artists and musical performers are able to cultivate freedom spaces where they are able to engage in whole body movement and what this means for their own development as people and as artists.

I’m working with Ben Rydal Shapiro, a researcher at Georgia State University, who has developed data visualization tools to support teaching and learning. One of the things Ben researches is the movement of bodies in space. He’s taken clips of the performances I recorded with collaborating artists and looked at the movement of their bodies in relation to time and space. It is not surprising that as percussionists and bass players, they are going to be using their hands and their feet. But they’re often using them together in a coordinated way while their eyes are closed. This coordination is tied to their processes for attending to one another and collaborating to co-create music. This stands in contrast to how people are taught to organize attention in school. In schools, visual attention often holds primacy. However, in this particular performance space, artists are drawing on multiple senses in order to fully participate and collaborate. So, we might ask what are the possible consequences for learning when we create spaces for sensory freedom.

And so, this is a a leap, but I don’t think it’s too far of a leap. If we think about the progression of schooling from early childhood spaces to high school, we are increasingly asking people to sit in ways that constrain their bodies, to not move their hands or their feet or other parts of their body unless they’re engaging in “productive activity”— like reading or writing—and to look at the front of the classroom. For example, when we go into some of the Math Science buildings [at UCLA], some of the chairs are bolted to the floor, [constraining] the design of the learning environment. I’m not saying every classroom should be an empty space, but we could pay more attention to how our bodies move and feel in spaces. There’s so much more we can do and experience as humans when we don’t put these kinds of constraints on ourselves.

Vocalist Zahra Baker worked with photographs of the artists’ ancestors to create quilt pieces for the group’s unique staging. Photo by Brenda Lopez

The improvisational artists who are participating in this project have a practice for setting up the performance, or teaching and learning, space. It is consequential for how the work that they’re about to do unfolds. Improvisation is not just about doing anything in the moment. They would say that they prepare for improvising, and they would probably say that it’s linked to their own spiritual development as people. When they get to a performance space, there’s a bunch of things they do, some of them very small, some of them larger. Some of it is about how they greet one another, but they are making decisions in that moment about how they’re going to set up the space and they are thinking about how these decisions might influence how the performance (or teaching and learning) unfolds.

I’m sharing this story because I’m involved in this other group with Indigenous scholars through Arizona State University. It’s a Mellon-funded project, and Natalie Diaz and Brian Brayboy are PIs on the project, looking at Indigenous forms of mentorship. I was sharing the experience of being with the musicians and observing them perform, and how they set up space.

Natalie suggested to me that the next time I teach, I invite students to first center themselves and then to move around the classroom and to sit wherever they felt comfortable–whether it was on a chair, on a floor, on top of the desks–and then to have a conversation about how that felt and what we wanted to do from there. I did this in a TEP class, and that was a really interesting day for me in the classroom. I think students appreciated it, and I also think they were kind of skeptical: “Okay, so we did this thing, and we get to collectively decide what we’re going to do. But is this for real? And will we continue to operate in this way?

I will say that this small practice that came from observing musicians, shifted the dynamics of my classroom space. What I’m looking for is not necessarily the big findings, but the small findings that can help us think about what we’re doing moment-to-moment, which is often a challenge when teaching because classrooms move so quickly. If we’re going to design something different, we have to be okay with what might come up with the unscripted, and that can be scary for teachers, for lots of reasons. It takes a lot of practice to slow down our own thinking and be reflective–not just to automatically respond to what’s going on, but to reflect in the moment and open up possibilities. I believe that one of the things we can learn from jazz artists who improvise is how to sit in/with dissonance while listening and watching for “light trails” that can take the group toward consonance.

Ed&IS: What about the dynamic of the artists’ interactions on and offstage?

Marin: These jazz musicians are creating something together as a group. We often ask people to teach on their own, with 20, 50, 100-plus students, depending on what grade level you’re at. It’s a very Western, individualistic kind of idea that a single educator will have all that knowledge to impart and that when unexpected things arise, we have the expertise to meet them.

Part of the preparation for [these] improvisers is getting out of their own way. It is about having the substantive knowledge and knowing enough. But there’s another level of preparation that is necessary, they would say, [to] be in the flow and open to possibilities as they arise. You’re open to being together and apart—you’re an individual, but you’re also a part of the group. You might lead, but then other times, you follow.

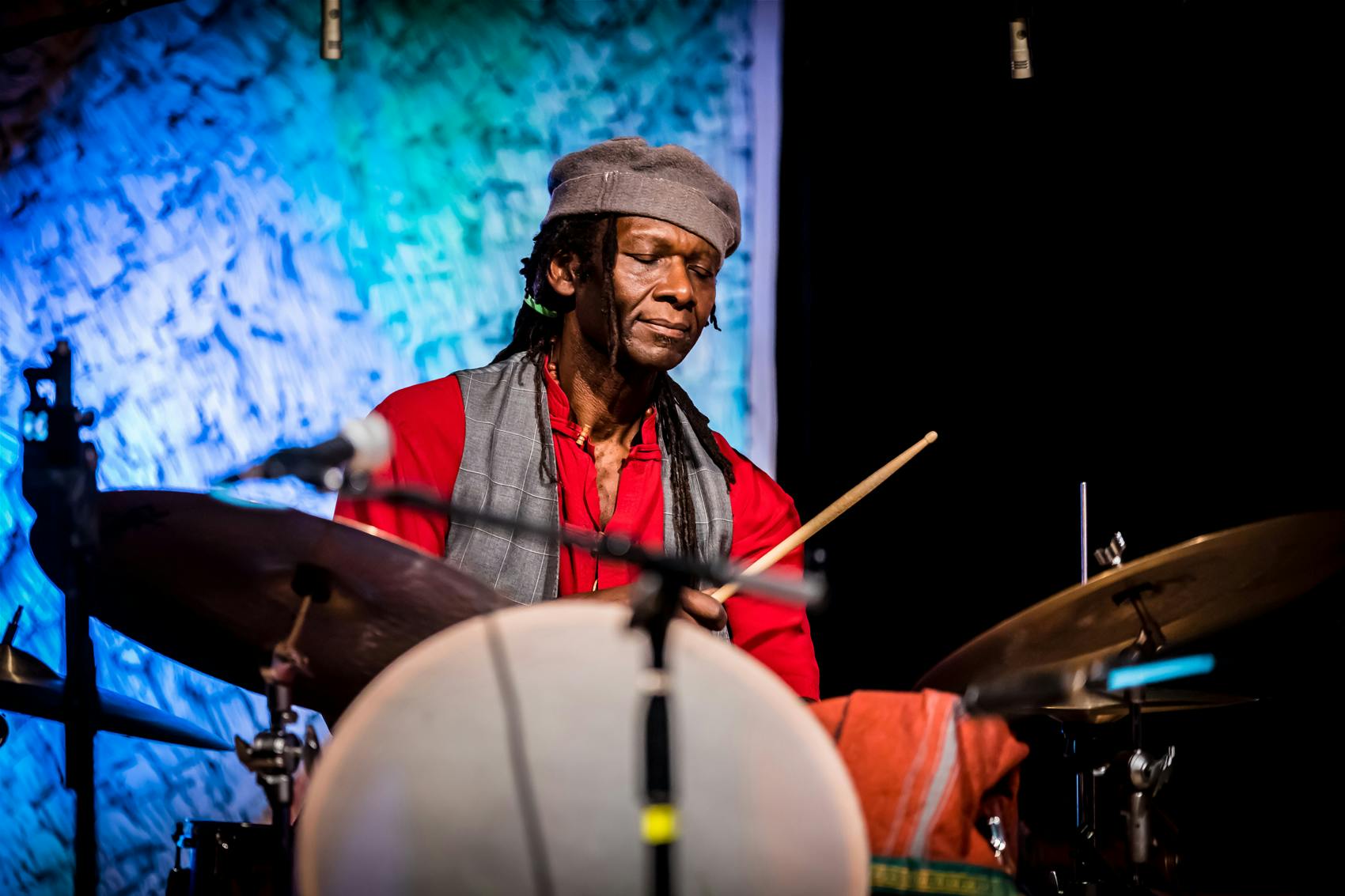

Hamid Drake, a prominent drummer in the creative music movement, performing in the “Moment to Moment Concert” in September 2022. Photo by Brenda Lopez

In the performance space, a feedback system is created. They come in and do the work together, but every show will vary based upon who is with them that day, who is starting, and who is in the audience. They would talk about this as a circulation of energy. We can ask ourselves as educators, “I have my lesson plan. What is the material that I want to cover today?” We can also ask ourselves, “What is the energy that I want to build in this space with others today?” We can ask ourselves about how we learn to be better attuned to one another and to ourselves, how we can be present, and how that feeds the creative process.

For example, this past July we organized a public performance at Experimental Sound Studio. Toward the end of the performance, the volume and speed of the music decreased and the sound of the leaves rustling and birds chirping became center stage. Many people in the audience felt this transition. At the same time, there was some uncertainty about whether or not “we” had come to a closing/end for this particular journey. It wasn’t until an audience member, who is the partner of one of the performers, said “thank you” that people began to clap.

Ed&IS: How do you hope that the focus of Prop. 28 on K-12 arts education will impact school cultures?

Marin: I deeply believe that the arts are an integral part of society. I was trained in the field learning sciences, where oftentimes if we’re studying the arts, it’s in service of STEM learning. I think that we can and should study the arts for art’s sake. I still think there are questions of equity in the arts and there are questions about the relationship between culture, gender, and race in the arts.

The group that I’m working with aren’t “standard” jazz artists. They would say they’re more part of the creative music or improvising music community. When John Coltrane’s music started to deviate from his original sound there was this question, “Is this still music?” In one of our research meetings, my father pointed out that Coltrane received “a vast amount of criticism and many people called it [the music] discordant, because he wasn’t playing that … which seemed familiar.” He also noted that Coltrane discovered something more and in doing so helped others to feel comfortable with feeling uncomfortable. This practice of bringing multiple dimensions of sound together allowed for processes of remembrance as well as creating new paths that are linked to self-determination and freedom. UCLA Professor of History Robin D.G. Kelley has written about this in his book, “Africa Speaks, America Answers.”

People still get pushed out of the arts because they’re doing something different or something that brings in a cultural perspective that is not appreciated or respected at the time. On the other hand, a lot of Indigenous artists are worried about how the visual arts, sound [arts], material arts–things that are closely linked to cultural practices and knowledge–can be misappropriated and used in ways that are not respectful. So, as a research community we need to be careful. We need to return to the 5 Rs.

Artists often use a different language around teaching and learning than many education researchers and learning scientists might. Recently, there’s been a focus around joy and education and Black joy. This focus is important and reminds us of the always present need to resist deficit orientations. Like scholars who attend to joy, these artists often talk about the power dreaming and spirit and love and wonder and beauty. All of these practices are important for our full development as humans.

Above: Professor Marin’s research included documenting the “Moment to Moment” concert, held in Chicago in September of 2022. As well as performing music, the collaborating artists created a specific environment through their set-up onstage, including the paintings of Lisa Alvarado, visual artist and harmonium player. L-R: Alvarado, Hamid Drake, drums; Joshua Abrams, bass; Michael Zerang, percussion; and Zahra Baker, vocals.

Photo by Brenda Lopez