Exploring the Role of Community Schools in the Development of Teachers & Teaching

By John McDonald

November 12, 2024

Read the magazine view of this article

Research presented at AERA highlights the work of the UCLA Center for Community Schooling in exploring the importance of teacher retention—particularly for teachers of color—and how California’s investment in the expansion of community schools may provide an opportunity for doing just that.

The COVID-19 pandemic worsened the challenges faced by too many children, shining a bright light on the inequities that plague our students, our schools, and the communities they live in.

In response, the State of California has made a multi-billion dollar investment in the expansion of community schools across the state. The idea is to accelerate the development of schools with a focus on whole-child education. Much of the conversation has focused on connecting “community schools” with a range of integrated services—healthcare, mental health counseling, economic assistance, and more—to address the social and emotional needs of children and families.

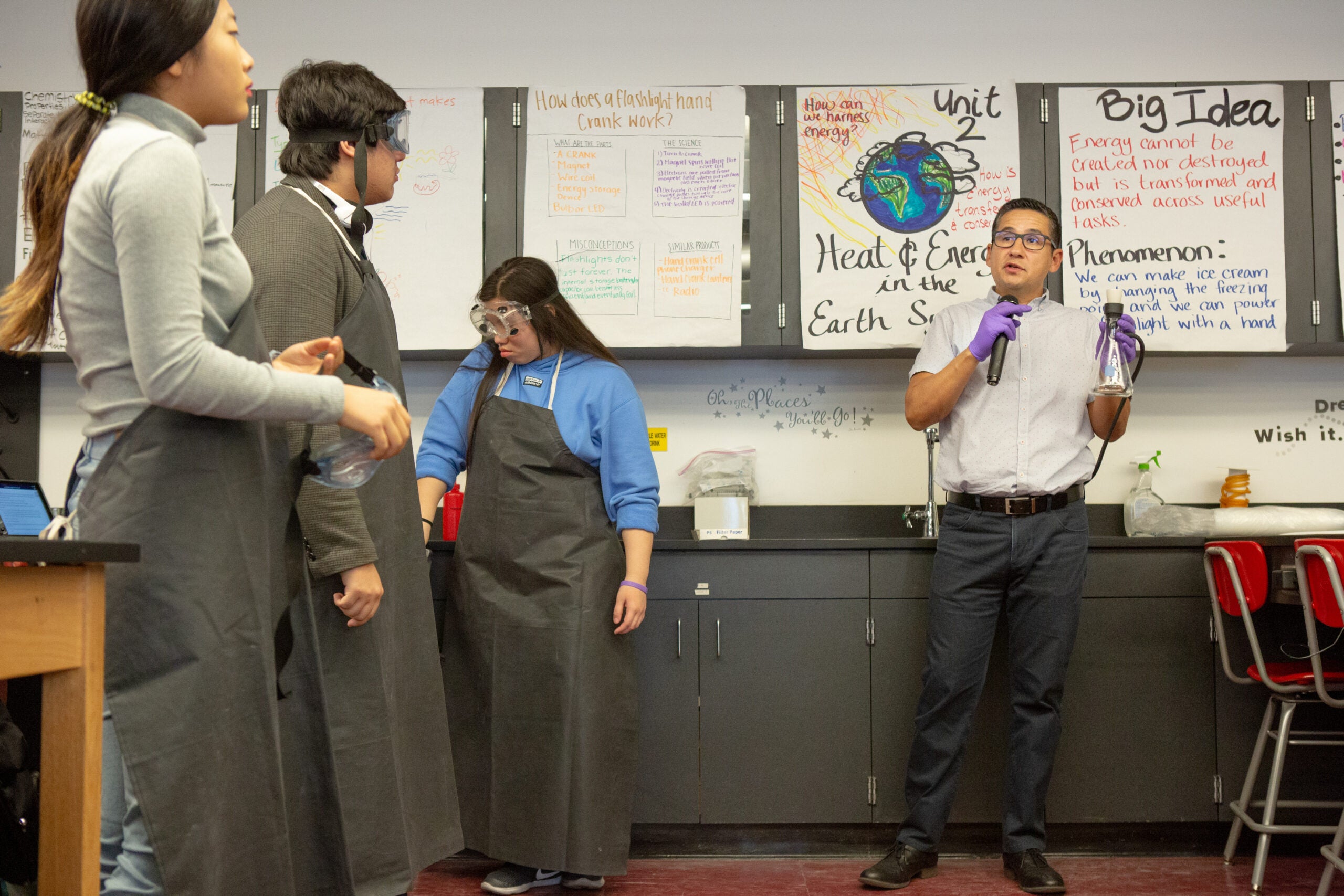

Those services are desperately needed and tremendously important. But as the community schools movement in California expands, education researchers at UCLA contend that whole-child education in community schools requires, “an intent focus on what happens in the classroom and really good teaching.”

“The role of teachers and teaching in community schools has been somewhat neglected,” says Marisa Saunders, lead researcher for the UCLA Center for Community Schooling (CCS). “We need to expand our focus beyond student supports and services to better understand what is going on in the classroom and the important role of teachers in community schools. A focus on teacher development and the supports they need are critical.”

Saunders believes that community schools can and should provide the workplace conditions and a learning environment that supports good teaching and student learning. And California’s investment in the expansion of community schools may provide an opportunity for doing just that.

“We have a perennial shortage of teachers and a huge need to recruit and retain teachers of color,” Saunders says. “Community schools may offer a potential strategy for helping us to do so.”

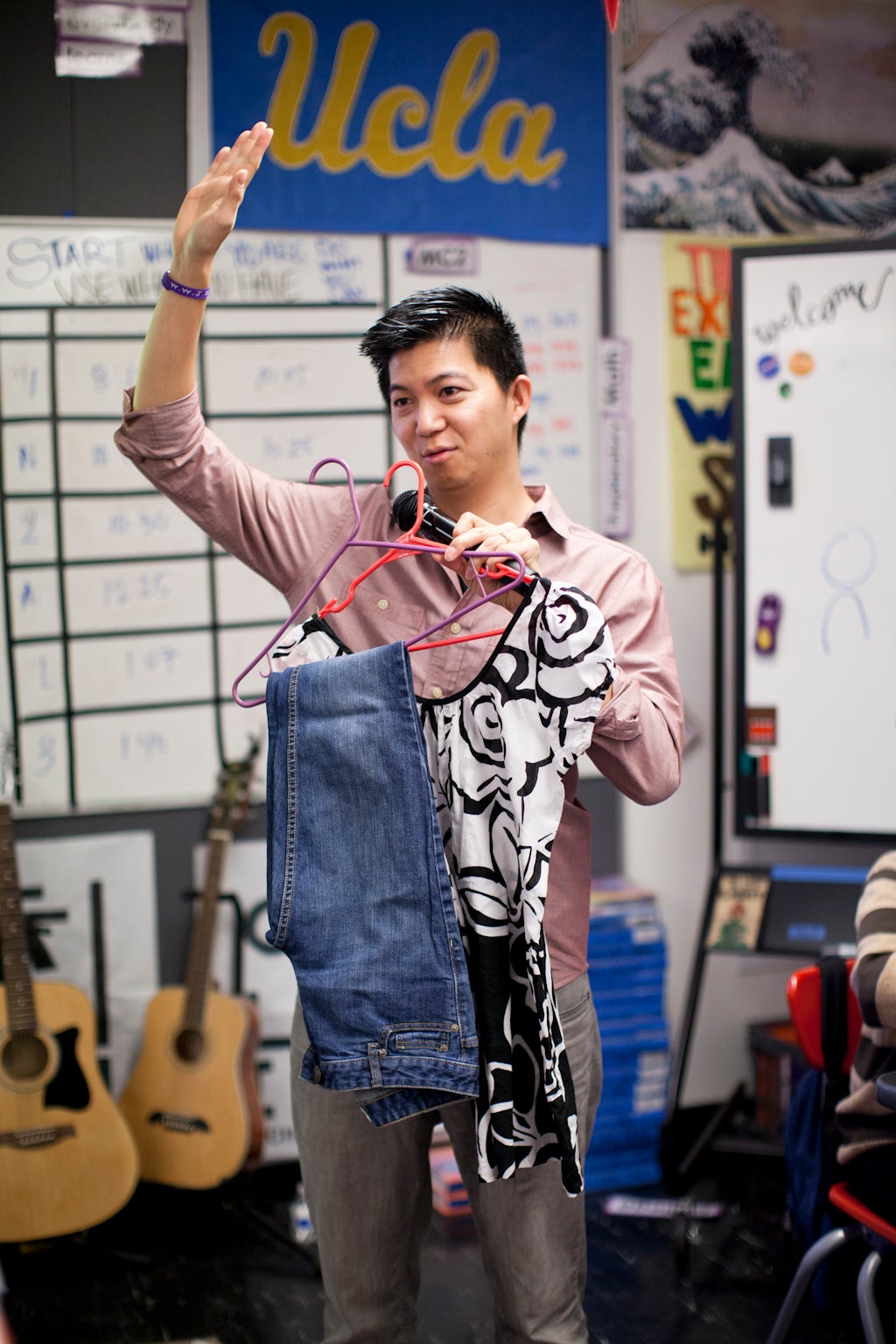

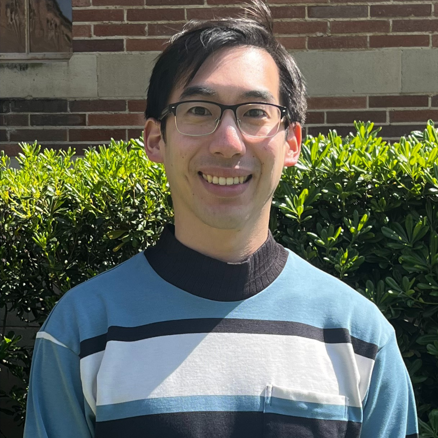

To explore this potential, researchers at UCLA CCS, with funding from the Hewlett and Stuart Foundations, began conducting research exploring community schools as a strategy for retaining teachers, particularly teachers who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). They wanted to examine the role of teachers in community schools where there is a focus on whole child education, what was happening with the retention of teachers, and why teachers leave the profession. The research team, including Natalie Fensterstock, Tomoko Nakajima, and Jeffrey Yo, presented their findings at the 2024 annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association (AERA) in Philadelphia.

“Our purpose primarily was to elevate the role of teachers and to engage in a discussion about teachers in community schools. The research presented provides valuable insights into the potential of community schools as learning environments that teachers actively shape, while also highlighting how that environment, in turn, influences teachers’ experiences,” Saunders says.

The UCLA team shared highlights of three research papers. Together, their research makes the case that whole-child education, like community schooling, requires a “whole teacher” approach. Teachers want to bring their full selves to their work, bringing their interests and activism to the classroom to help students. Systems need to be developed to support teachers as trusted “agents” and leaders to craft and design learning. And that these conditions can influence teacher satisfaction and retention.

AERA RESEARCH PRESENTATION: Teachivist: Community Schools as a Setting for “Transformation in Our Society”

By Tomoko M. Nakajima, UCLA Researcher

Nakajima’s presentation highlighted findings from a research-practice partnership conducted with UCLA colleagues Marisa Saunders, Darlene Tieu, and Rosa Jimenez. In this secondary data analysis, the team looked at 53 interviews conducted with teachers at a local public school district. Their analysis explored what features at community schools attract Black, Indigenous and other people of color (BIPOC) as teachers and how the strategy might encourage stronger BIPOC teacher retention than at traditional public schools.

“The term teachivist emerged in the first year of our data collection,” said Nakajima, “It was a portmanteau invented by a study participant—a BIPOC community school teacher—who was telling me about the sense of camaraderie that they felt with their colleagues. Teacher combined with activist became this word, teachivist. That delightful moment inspired this new inquiry.”

By focusing on how BIPOC community teachers spoke about their passions, values, and past experiences, Nakajima found that their activist leanings motivated BIPOC individuals to choose the teaching profession and drew them to the community schools they currently serve. They were also integral to their daily work, as teachers strengthened their commitment to their place of work, their coworkers, and their students. Teachivists recognize and challenge inequities and aim to inspire and mobilize their students. They value solidarity, supportive leadership, and ongoing professional learning.

Nakajima said that in the interviews, “Our participants had identified as activists long before they became teachers. They had spoken animatedly about recognizing and calling out societal inequities, expressing dissenting opinions they held, and about wanting to disrupt the status quo in education.” This identity played out in participants’ pathways into teaching. One teacher explained that theirs was a deliberate choice to teach in the neighborhood public school where they grew up because they were “giving my community the education that we deserve.”

After choosing teaching as their career, BIPOC community teachers said they sought workplaces where the con-ditions were ripe for activism, where they could work as catalysts for social movements alongside like-minded folks where the movement was already in motion. This sense of solidarity with others on campus was a powerful and necessary condition of their employment. Teachers in the study also deliberately navigated toward schools where the leadership and governance structures supported teachivism and offered an atypical level of trust and classroom autonomy from the powers that be.

When asked what strengthens BIPOC teacher retention, participants responded that they wanted to grow in their capacity to serve their students and be on a never-ending continuum of learning. They called for ongoing guidance and learning opportunities to help them adapt with the times and push against normative practices. Teachivists challenged themselves and their colleagues to do better and bring about positive change in the world.

Nakajima hypothesized that community schools, which aim to center social justice, teacher leadership, and integrated supports, can be attractive workplaces for BIPOC teachers looking to align their values with their school’s unifying principles. With site leaders who encourage, appreciate, and amplify teacher voice, community schools can catalyze transformative change in education and simultaneously sustain BIPOC teacher retention.

“These practices and conditions can be adopted anywhere, not just in community schools, and they should be, according to our participants,” said Nakajima. “Doing so would undoubtedly protect and strengthen the profession for all teachers.”

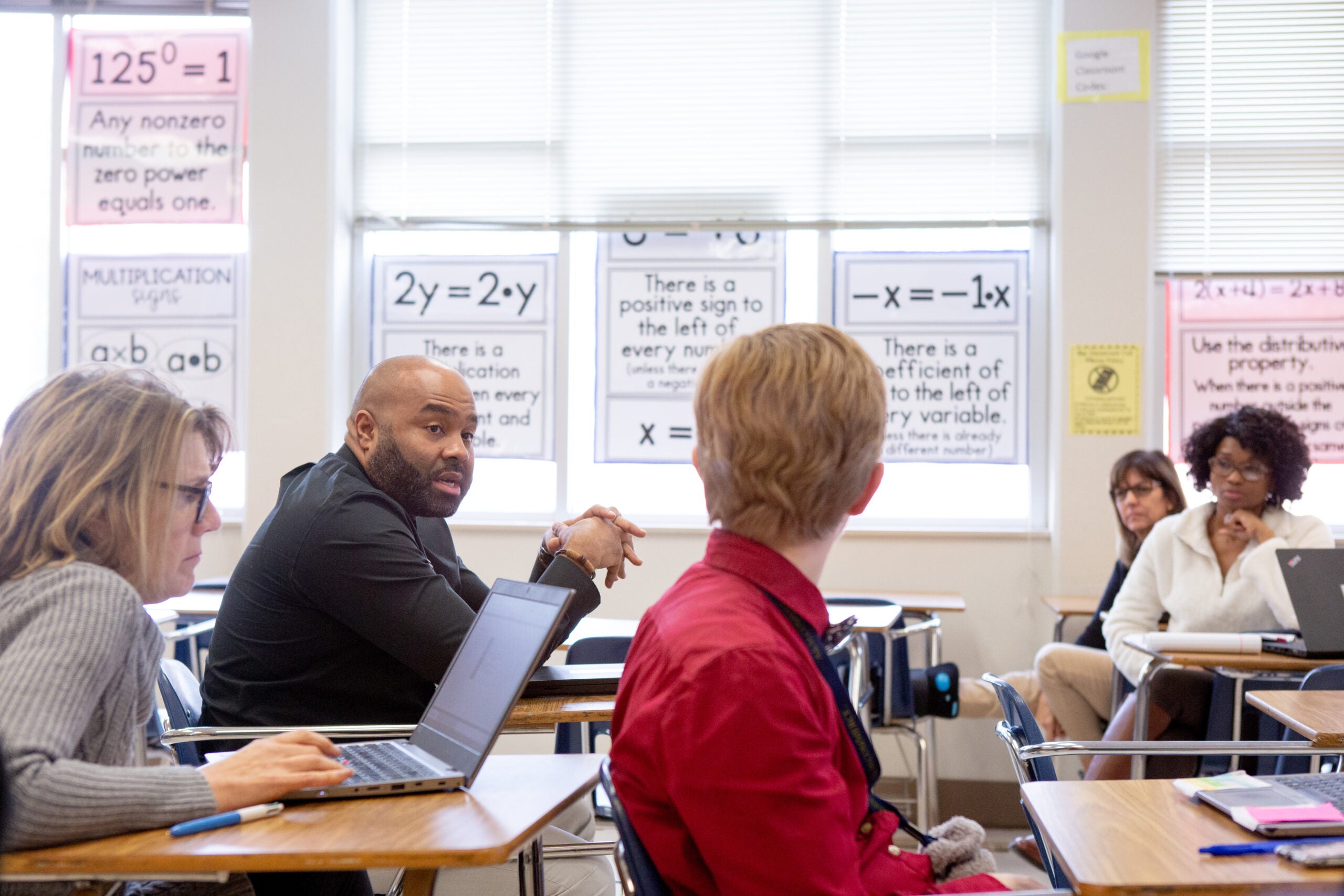

AERA RESEARCH PRESENTATION: “You Can’t Talk About the Whole Student Without the Whole Teacher”

By Natalie Fensterstock, UCLA Doctoral Student

The presentation draws on the study, “Beyond Teacher Leadership: The Role of Teachers as Learners, Innovators and Designers for Whole Child Education,” conducted by Fensterstock and Saunders in collaboration with Barnett Berry and Peter Moyi at the University of South Carolina. Karolyn Maurer of UCLA also contributed to the study. The research looks at how two school districts, Surrey in British Columbia and Anaheim Union High School District in Southern California, supported whole-teacher development in community schools.

“We were really focused on understanding district systems of support for teachers and how those district systems of support enabled teachers to deliver on the promise of whole child education,” Fensterstock says. “We were trying to understand what it took to support teachers by exploring the perspectives of district staff, teachers, and teacher coaches.”

The presentation explored the idea that education systems need to be developed to support teachers as “agents,” trusted as leaders to craft and design learning.

The findings highlight the ways that schools and districts understand the concepts of whole teacher and whole teacher development, underscoring the need to put teachers first.

They also identify conditions of whole-teacher development with a focus on school or district approaches aimed at holistically supporting teachers. These include a space for open and honest feedback, a willingness to innovate and collaborate, and a focus on relationships and building a sense of belonging. Teachers also need opportunities for personal development.

Fensterstock’s presentation emphasized the need for systemic support, including release time for professional development and collaborative leadership. She also highlighted the moves the districts made towards curricula that focus on student competence in subject matter content, self-assessment, and holistic assessment systems. The conversation also highlighted the importance of systemic support for teacher well-being, such as non-evaluative peer coaching, collective efficacy, and release days for collaboration.

By treating teachers as professionals and fostering a supportive environment, Fensterstock noted, community schools potentially can improve teacher retention and job satisfaction.

“Community school teachers are whole child teachers,” Fensterstock said. “These are teachers that collaboratively design learning opportunities for school and community, who promote a culturally responsive curricular approach that builds on students prior learning, identity development, and local community needs and assets. They adapt curriculum to address real-world challenges and center social and emotional learning alongside traditional academic content. They are focused on building trusting relationships with students and families.

“We need to really think about the role of the district and the role of supporting these teachers from the systems level,” Fensterstock concluded.” It cannot simply be individual-level approaches. We need systemic solutions to systemic issues.”

AERA RESEARCH PRESENTATION: “Exploring Teacher Satisfaction and Teacher Retention in a District Supported Community Schools Initiative”

By Jeffery Yo, UCLA Researcher

Jeffrey Yo examines BIPOC teacher retention and the experiences of BIPOC teachers in community schools. The study is part of a three-year longitudinal partnership between UCLA and a large urban school district implementing a community schools initiative. The district’s community schools director is a co-author. The mixed methods study seeks to understand the ways community schools can be an effective strategy for teacher retention.

Yo began by sharing data on the racial divide and teacher shortage. Over half of K–12 students in the U.S. are Black, Indigenous, or other people of color (BIPOC), but less than 30 percent are BIPOC educators. The racial divide stems in part from ongoing teacher shortages in K–12 schools. The problem has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In a 2022 National Education Association survey of teachers, more than half (55 percent) said they planned to leave the profession. The number was even higher among Black and Latino teachers. California schools face similar challenges.

Yo’s presentation looked at the potential of community schools to address the retention of BIPOC teachers and their experiences in community schools to understand the ways community schools can serve as an effective strategy for teacher retention.

“One thing that’s special about community schooling is that it’s a promising strategy for retaining BIPOC teachers,” Yo said. “As democratic spaces, they can empower teachers and be a place for them to serve as activists and leaders where they can grow and thrive. There’s this idea that community schools can address issues that often lead to teacher attrition, such as feelings of isolation, frustration, and lack of influence.”

Analyzing human resources data from the participating school district, the study compared retention rates between community schools and traditional public schools, finding similar rates but noting higher retention in community schools at the elementary level. It is less clear whether community schools or traditional schools had higher retention rates overall.

Another key aspect of the research is a focus on the “shifting” rates of teachers in community schools versus traditional schools and its impact, if any, on teacher retention. “Shifters” are classroom teachers who may leave the classroom to take on an out-of-classroom teaching role, such as an instructional coach or coordinator or an administrative role but stay within the school. The analysis calculated the BIPOC Teacher Retention/Shifting rate for each school in the study.

Research suggests that higher rates of shifting may support BIPOC teacher retention.

“Community Schools might utilize teacher shifting more than traditional public schools as a strategy to retain staff,” Yo said. “This approach may foster a more supportive teaching environment, where the school community supports teachers’ roles both inside and outside the classroom, allowing them to continue contributing to the school in various capacities.”

Community schools at the elementary grade level had higher or equal in-school shifting rates among BIPOC teachers compared to traditional elementary schools. Community schools at the middle and high school grade levels showed higher shifting rates for BIPOC teachers compared to traditional schools, with some nuance in the data for differing years.

Yo’s presentation underscored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teachers in community schools and the implications for teacher retention. Previous research has illustrated challenges related to pandemic-induced trauma, and case-study findings reveal that BIPOC teachers experienced student and family trauma, complicating their retention in the school. Overall, the findings indicate that BIPOC teacher retention is similar between community schools and public non-community schools in the school district. Retention and shifting rates varied by school type, but the differences were not significant enough to indicate a true disparity. That said, elementary community schools showed slightly higher retention, which may suggest that community schools support BIPOC retention.

To better understand how community schools support BIPOC teachers, Yo is expanding his analysis to a larger sample of community and traditional public schools, with a focus on specific teacher subgroups to determine which schools and teachers benefit the most.

The study recommends that community schools embrace efforts such as in-school shifting as a school practice that enables teachers to move in and out of the classroom as needed yet remain connected to their school community. It also recommends policies and initiatives that sustain and support a whole-teacher approach wherein teachers can integrate all aspects of themselves into their work while receiving holistic support—not only for their pedagogy but also for their physical, emotional, and mental well-being.

The researchers contend that these policies, such as rebuilding practices that promote teacher collaboration, strengthening teacher-community connections, providing stable school administrations, and fostering democratic leadership, can empower and support teachers and ultimately help them foster long and fulfilling teaching careers.

“The research presented by our team at AERA represents a growing and exciting body of work focused on community school teachers,” says Saunders. “With a focus on teachers, it offers important contributions to a more complete understanding of the potential of community schools as places that can tend to the needs of the whole child and the whole teacher.

“Our hope is that this research will help policymakers and education leaders to understand that a focus on whole-teacher supports, in community schools and beyond, represents a potential strategy for California to strengthen its teaching recruitment and retention efforts. Let’s take what we’re learning from the research and create the spaces teachers need so that they can thrive in the profession to which they were called.”